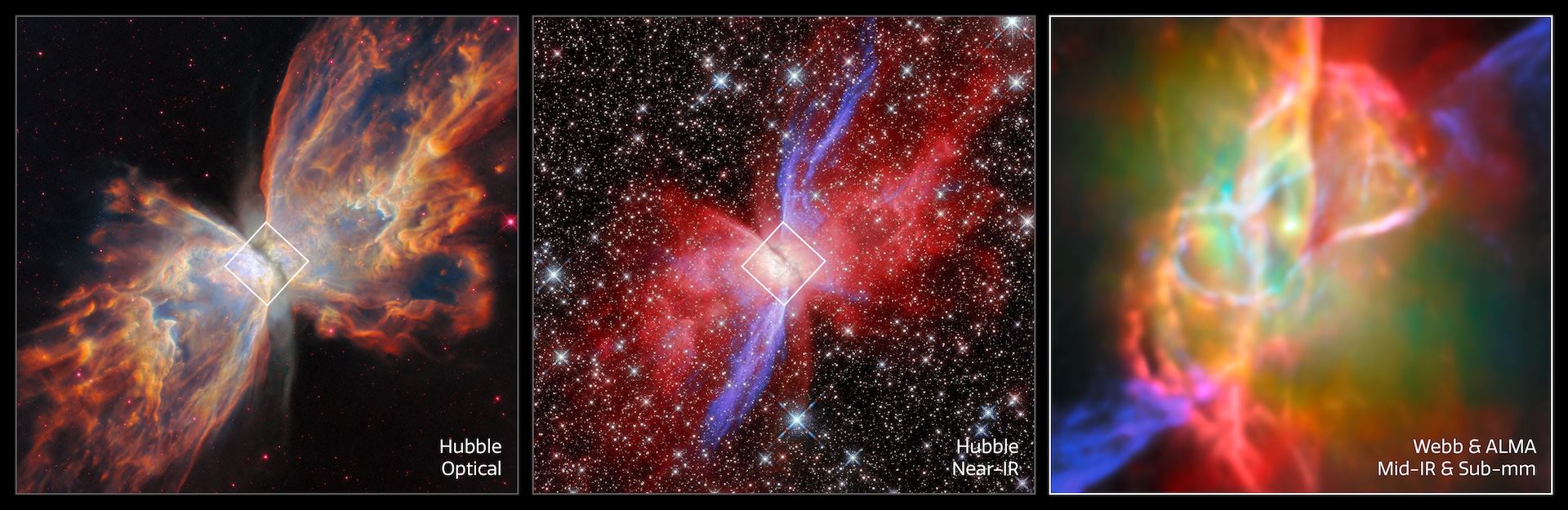

'Cool gemstones' and 'fiery grime': James Webb telescope finds clues to Earth's origins in dazzling new view of Butterfly Nebula

In a dazzling new photo, the James Webb Space Telescope zooms in on the Butterfly Nebula — the dying gasps of one of the hottest stars in the sky, which could hold clues to Earth's origins.

(Image credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, M. Matsuura, ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), N. Hirano, M. Zamani (ESA/Webb))

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Apologies, birds of the cosmos — the James Webb Space Telescope has set aside ornithology and officially entered its entomology era, a stunning new image of the Butterfly Nebula shows.

Glittering some 3,400 light-years from Earth in the constellation Scorpius, the Butterfly Nebula (officially designated NGC 6302) is the swan song of a dying star. At its center sits one of the hottest known stars in the Milky Way: a white dwarf (the collapsed husk of a once-sunlike star) smoldering at temperatures of more than 220,000 kelvins (nearly 400,000 degrees Fahrenheit). As it slowly dies, the star sheds its outer layers as twin lobes of hot, irradiated gas, which form the brilliant "wings" of the butterfly.

Scientists have observed the nebula before with the Hubble Space Telescope, which captured the cosmic butterfly's wing-like outflows and blazing stellar center. However, new infrared observations taken with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) reveal details that were previously invisible — including the clear outline of the nebula's central star, a writhing "doughnut" of dusty gas swirling around it, and twin jets of energy firing off into space.

The JWST observations not only reveal new insights about the messy process of stellar death but could also help researchers better understand how the ingredients of Earth-like planets are recycled through space.

"This discovery is a big step forward in understanding how the basic materials of planets come together," lead study author Mikako Matsuura, an astrophysicist at Cardiff University, said in a statement. "We were able to see both cool gemstones formed in calm, long-lasting zones and fiery grime created in violent, fast-moving parts of space, all within a single object."

NGC 6302 is a planetary nebula — so named because early astronomers sometimes mistook the bright, round objects for planets when viewing them through telescopes of the time. In fact, there is no planet to be seen here — just a dying star throwing its final tantrum.

Related: James Webb telescope images reveal there's something strange with interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS

When massive stars die, they fuse increasingly heavy elements in their cores, before finally exploding and casting that material out into the cosmos. By analyzing the nebula's various components with JWST, the researchers spotted traces of quartz, iron, nickel and carbon-based molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

According to the researchers, it's likely that these organic compounds form when a hot "bubble" of wind from the central star slams into the gas around it. These dusty particles may one day become the building blocks of rocky planets, the researchers said.

The research was published Aug. 27 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus