10 mind-boggling deep sea discoveries in 2023

Scientists have made some intriguing discoveries exploring the deep sea this year. Here are some of our favorites.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The deep sea is an enigmatic, alien world. But every year, scientists make discoveries about the ocean's depths that help to fill in parts of the puzzle, and this year was no different. From gigantic seamounts and the deepest-dwelling fish to a mysterious golden orb and puzzling methane leaks, here are the 10 best deep-sea discoveries of 2023.

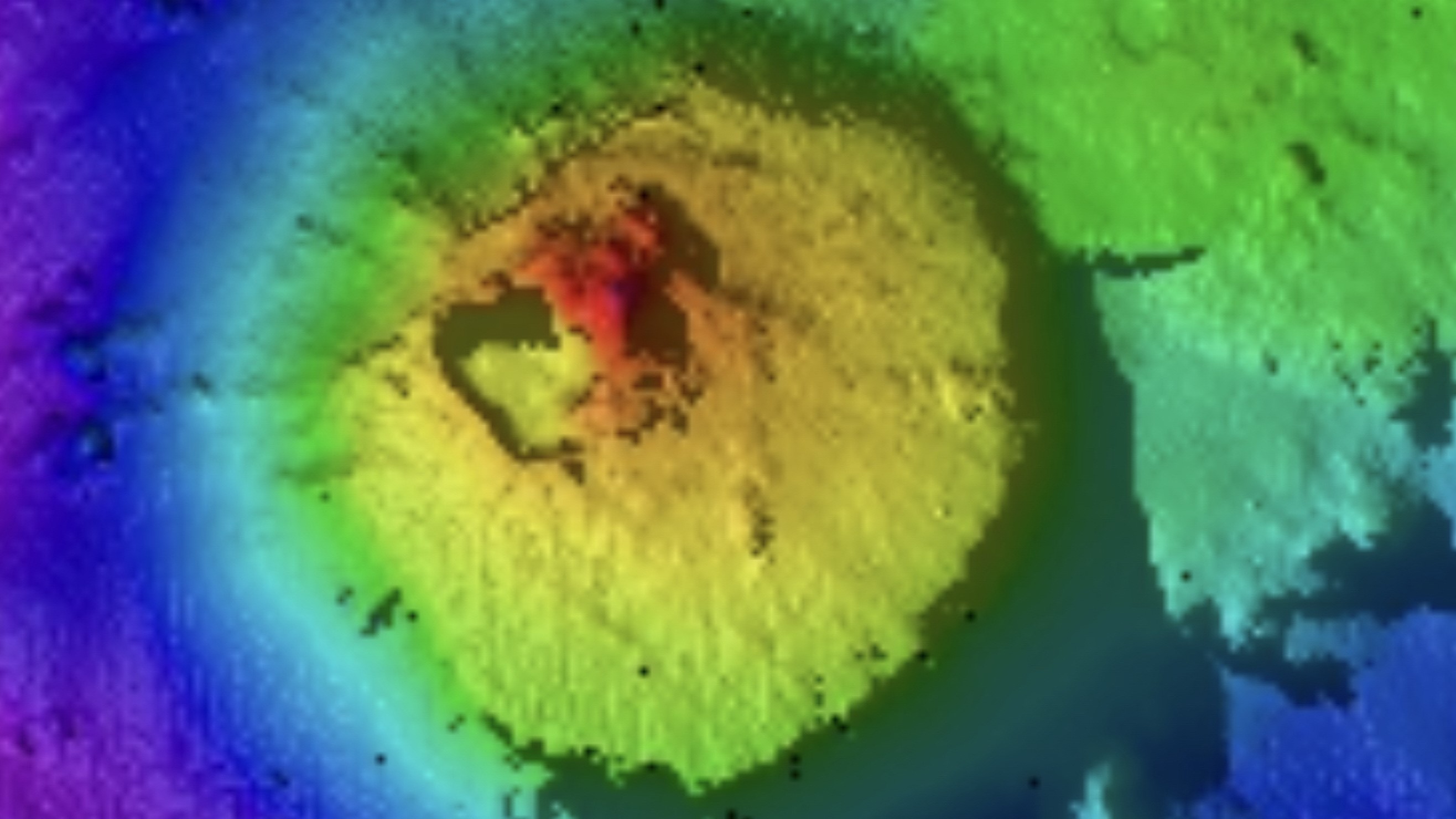

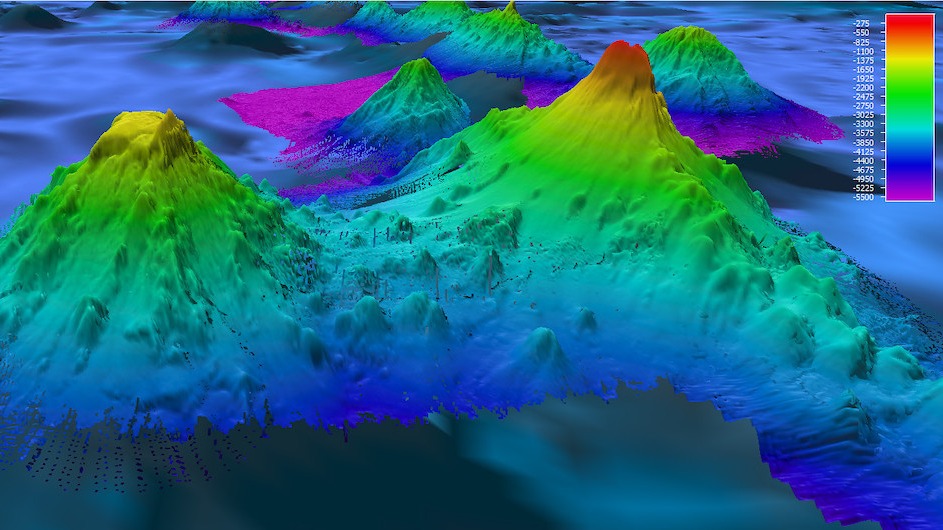

Gigantic seamount

In November, researchers mapping the seafloor near Guatemala discovered a gigantic underwater mountain, or seamount, that is twice as tall as the world's tallest building, the Burj Khalifa.

The 5,250-foot-tall (1,600 meters) cone-shaped structure, which lies 7,870 feet (2,400 m) below the ocean's surface, is the remnant of an ancient underwater volcano and covers around 5.4 square miles (14 square kilometers). Researchers discovered it using multibeam sonar during a six-day crossing between Costa Rica and the East Pacific Rise — a tectonic plate boundary in the mid-Pacific Ocean.

Seamounts provide crucial rocky habitats for deep-sea corals, sponges and a host of invertebrates. Experts estimate that there are at least 100,000 undiscovered seamounts in the world's oceans.

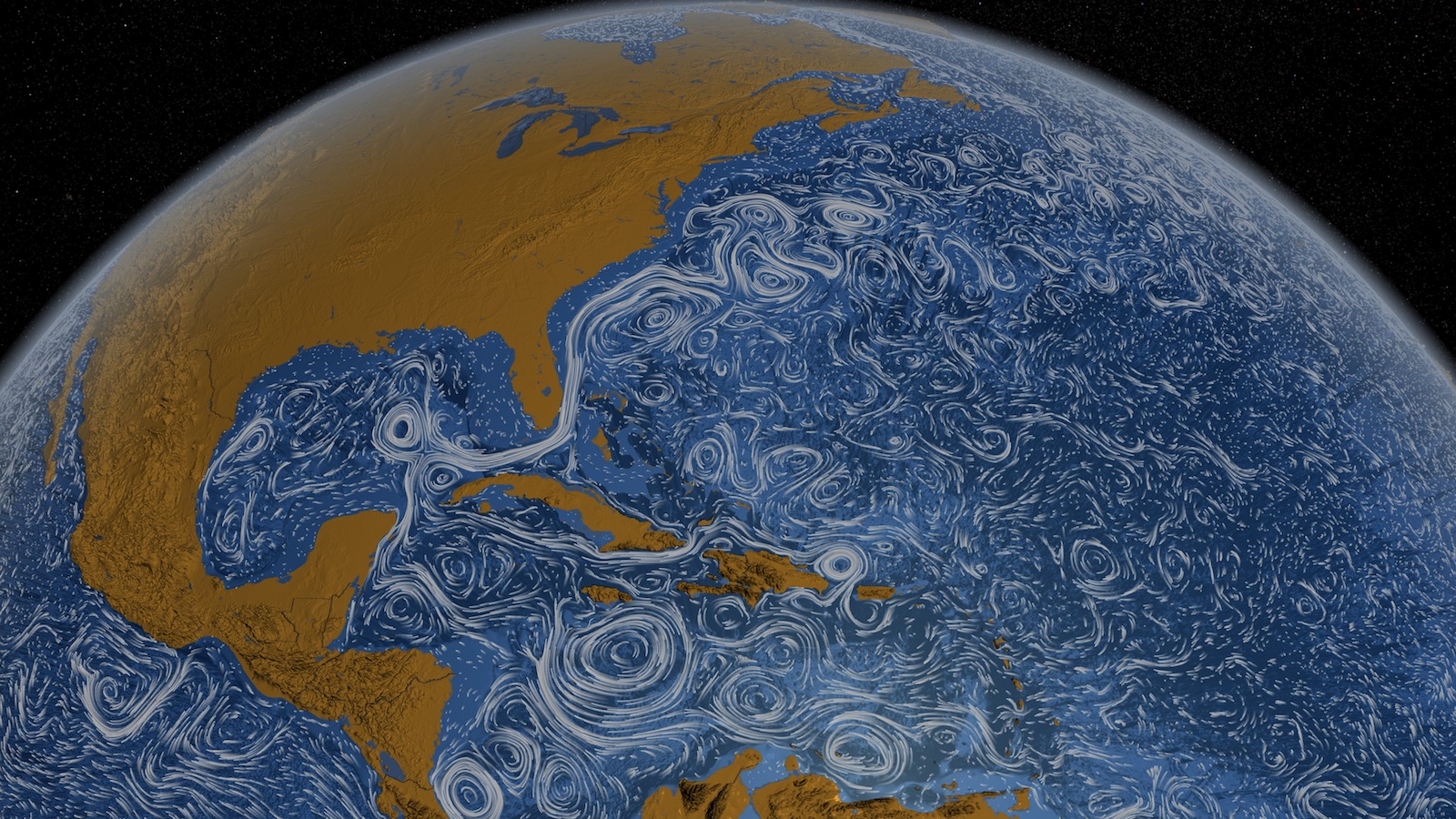

Seafloor heat waves

In a March study, researchers revealed that some of the ocean's deepest points have likely been experiencing previously unknown heat waves that threaten the creatures living there.

Heat waves near the ocean's surface, which are the result of human-caused climate change and oceanographic phenomena such as El Niño, have been documented for decades. But a computer model using surface temperatures and ocean currents showed that the seafloor is probably also experiencing what researchers refer to as "bottom marine heat waves."

These deep-sea heatwaves can be even more extreme and last longer than surface heat waves, the models revealed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Seafloor ecosystems are often populated by lobsters, scallops, flounder, cod and other commercially fished creatures, which means bottom marine heat waves could have serious financial implications as well as being ecologically destructive.

Mysterious golden orb

In September, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) researchers dredged up a mysterious golden orb from the seafloor in the Gulf of Alaska. Initial analysis revealed it was "biological in origin" — but scientists had no idea what it was.

Researchers plucked the golden orb from a seamount around 10,825 feet (3,300 m) below the surface using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). The mysterious object was around 4 inches (10 centimeters) wide and appeared to be attached to a rock. When it was pulled to the surface it lost most of its structure and "melted" into a gloopy pile.

Scientists were divided on what the orb was — some thought it was an egg case and others suspected it was a sponge, while others noted it could also be something else entirely. And the orb's identity is still unknown.

The orb's gold color is also a mystery. "Since no natural light penetrates to these depths, it's often hard to determine why certain colors emerge," researchers wrote.

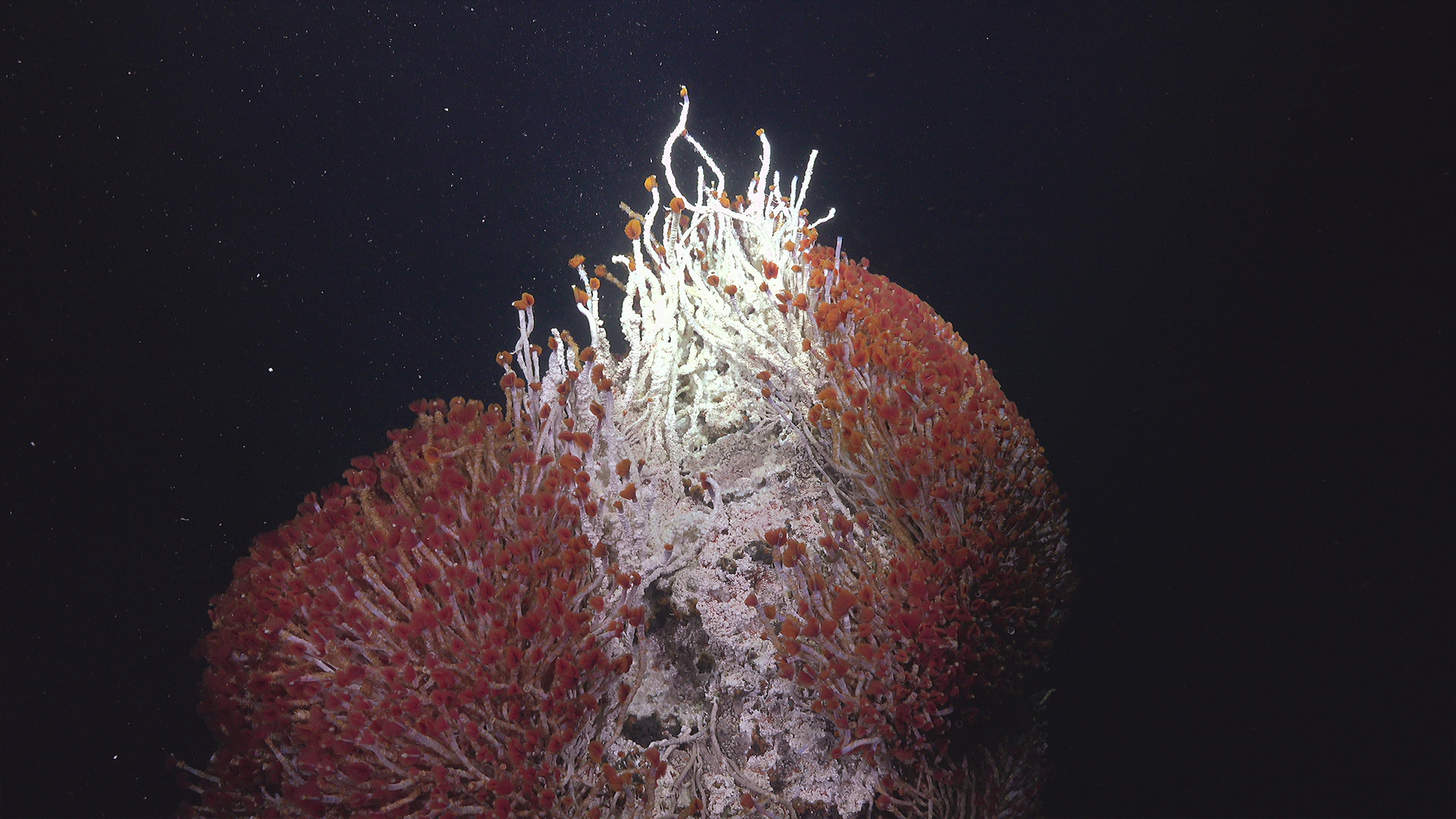

Egg-covered volcano

In July, researchers explored an ancient deep-sea volcano off Canada's Pacific coastline and discovered that it was surprisingly still active — and covered in up to 1 million football-size eggs.

The underwater mountain, which towers 3,600 feet (1,100 m) above the seafloor, was spouting warm, nutrient-rich water that sustained a thriving ecosystem of deep-sea corals and a nursery for Pacific white skates (Bathyraja spinosissima) — little-known sea creatures related to sharks and rays.

The skates had laid countless rectangular-shaped eggs, known as mermaid's purses, on the seamount. Scientists estimated there could be anywhere from 100,000 to over a million eggs in the area. When these eggs hatch, the seamount likely provides an ideal habitat for the juveniles to grow before heading into the wider ocean.

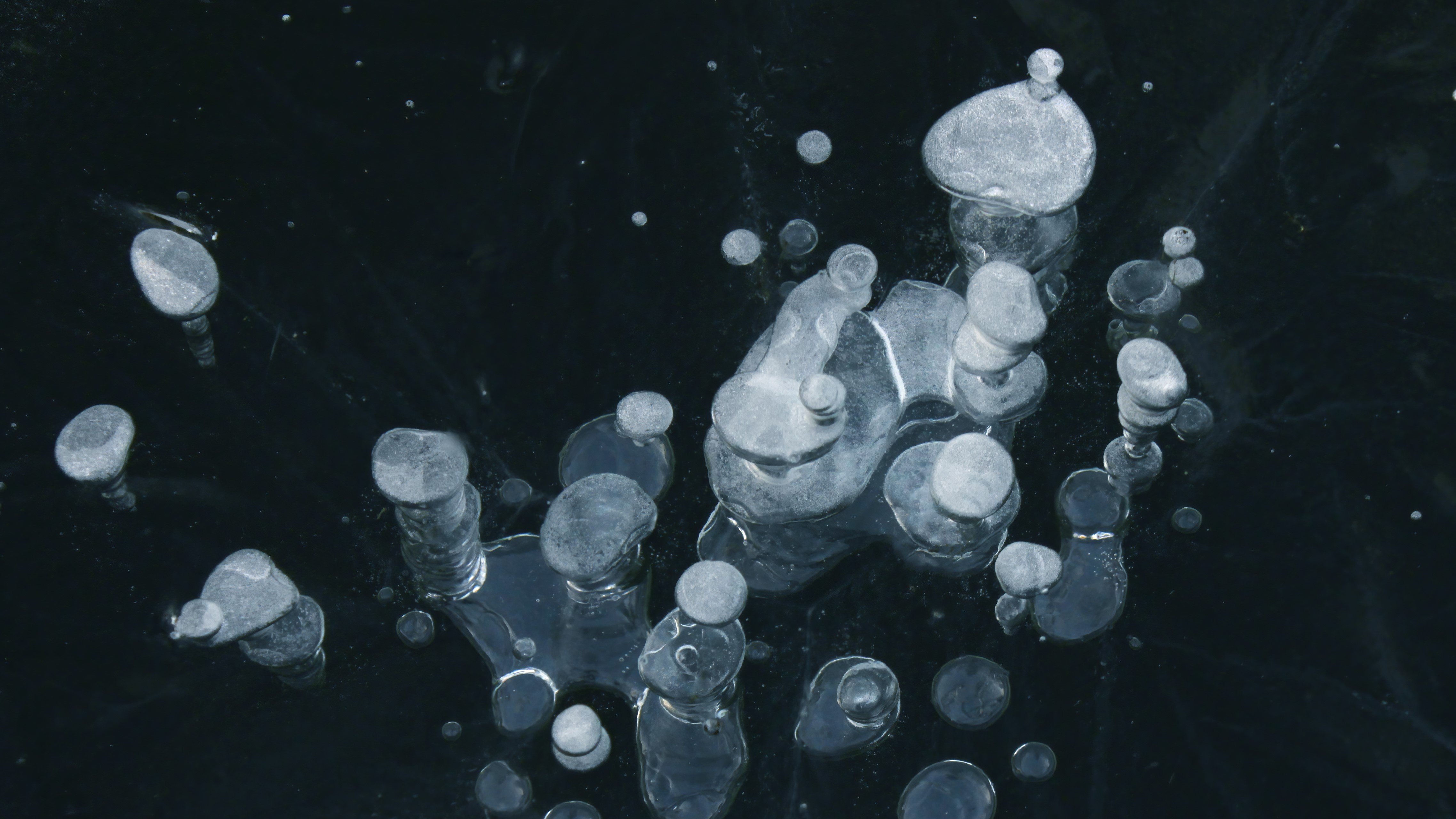

Baffling methane leak

In August, researchers discovered an enormous, puzzling methane "leak" coming from the bottom of the deepest point in the Baltic Sea.

The team found that the greenhouse gas was "basically bubbling everywhere" from an area covering roughly 7.7 square miles (20 square km) — around 4,000 soccer fields — at a depth of about 1,300 feet (400 m).

The bubbles were also rising much higher than similar methane emissions across the globe. Normally, methane gets dissolved in deep waters and rarely travels more than a few hundred feet above the seafloor. But the gas rising from this area reached up to around 65 feet (20 m) below the ocean's surface, which is "completely new."

The researchers think the methane is coming from decaying organic matter on the seafloor, but it is unclear why there is so much of it and why it is rising so high up in the water column.

Deepest-dwelling fish ever

In April, scientists released eerie footage of a group of ghostly white fish swimming around the seafloor more than 5 miles (8 km) beneath the waves in one of the world's deepest trenches.

The unidentified species of snailfish, which likely belongs to the genus Pseudoliparis, was spotted by researchers controlling an ROV in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench near Japan at a depth of 27,349 feet (8,336 m), which is more than 500 feet (150 m) deeper than any fish have been seen before.

The immense pressure at this depth would crush most fish. But snailfish have replaced their scales with a gelatinous layer that helps absorb this pressure. The snailfish also contain special chemicals that protect them on a cellular level.

On the same expedition, researchers trapped and dragged up two snailfish in the nearby Japan Trench at a depth of 26,319 feet (8,022 m), which makes them the deepest fish ever caught by humans.

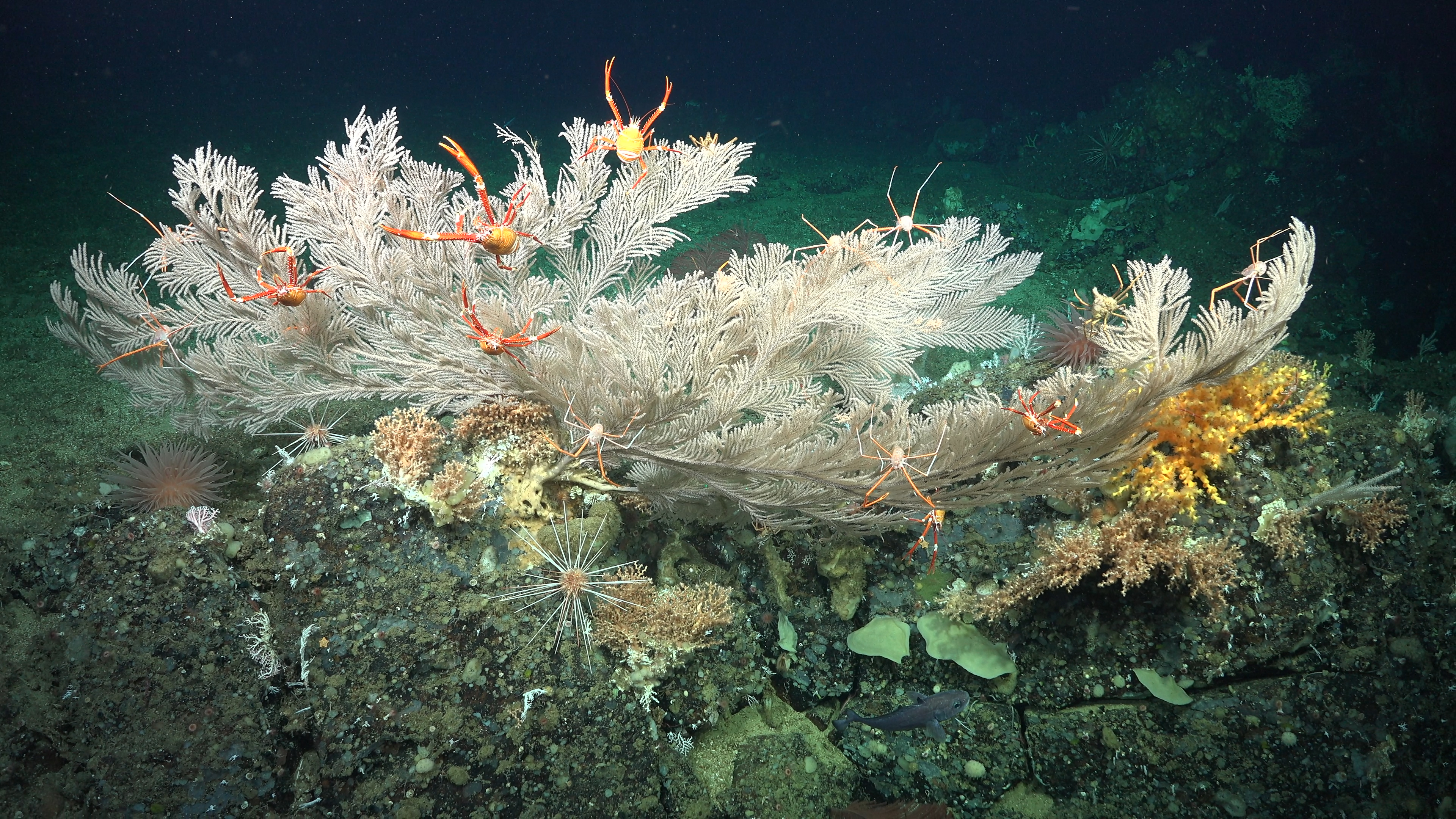

Deep-sea coral reefs

During a 30-day expedition off the coast of Ecuador, ocean explorers discovered a pair of pristine, deep-sea coral reefs near the Galápagos Islands.

The reefs sit at around 1,000 feet (300 m) beneath the ocean surface, which is much deeper than most coral reefs, and the larger of the two is more than 2,600 feet (800 m) long.

The reefs feature a rich diversity of stony coral species that have likely thrived there for thousands of years. They are home to lots of other creatures including crustaceans, anemones, brittle stars and urchins.

The expedition also confirmed the existence of two seamounts in the nearby area, which scientists had previously detected in satellite data.

'Pristine wilderness' under threat

In a May study, researchers revealed that one of the most promising sites for future deep-sea mining activities is home to more than 5,000 newly identified animal species, which could all be in imminent danger if humans start mining the area.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is a large seafloor deformation that stretches from Mexico to Hawaii and covers around 2.3 million square miles (6 million square km), which is around 3.5 times the area of Alaska. It is covered in potato-size spherical nodules that are rich in highly desired metals such as manganese, cobalt and nickel, as well as small concentrations of extremely valuable rare earth elements.

Researchers analyzed more than 100,000 individual records collected from the area and estimated that 90% of the species they identified could be new to science. Deep-sea mining, which could begin properly in the next few years, could threaten all of these species.

"With the possibility of mining looming, it's doubly important that we know more about these really understudied habitats," researchers wrote.

Hidden underworld

In August, scientists exploring a hydrothermal vent field in the Pacific Ocean discovered a hidden ecosystem buried beneath mini volcanic cones.

The hydrothermal vents, which are located in the East Pacific Ridge near Central America, have been studied for more than 40 years. But for the first time, researchers looked beneath the vents by scraping away the ocean bottom sediment using the robotic arm of an ROV. In doing so, they discovered a wide diversity of sub-seafloor creatures including worms, snails and deep-dwelling octopuses.

"This truly remarkable discovery of a new ecosystem, hidden beneath another ecosystem, provides fresh evidence that life exists in incredible places," researchers wrote.

'Mind-boggling' volcano map

In April, researchers published a "mind-boggling" map of more than 19,000 underwater volcanoes across the globe, most of which were newly discovered.

Researchers used radar data from multiple satellites to complete the map. The satellites looked for tiny deviations in gravity created by the seamounts and were able to spot underwater mounds as small as 3,609 feet (1,100 m) tall.

The team thinks the map could help scientists learn more about ocean currents, plate tectonics and climate change.

The map is one of the most complete seamount compendiums ever created, but researchers still think there are thousands of undiscovered structures littering the seafloor.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus