Army of swimming microbots eradicate deadly pneumonia infection from mice lungs

The unorthodox therapy could soon be used on humans.

Researchers have successfully eradicated deadly pneumonia infections from the lungs of mice by pouring armies of swimming microbots down the rodents' windpipes. The unorthodox treatment, which directly targets the site of the infection, was 100% effective at curing infected mice and if follow-up studies show it also works in humans, could one day be used in people.

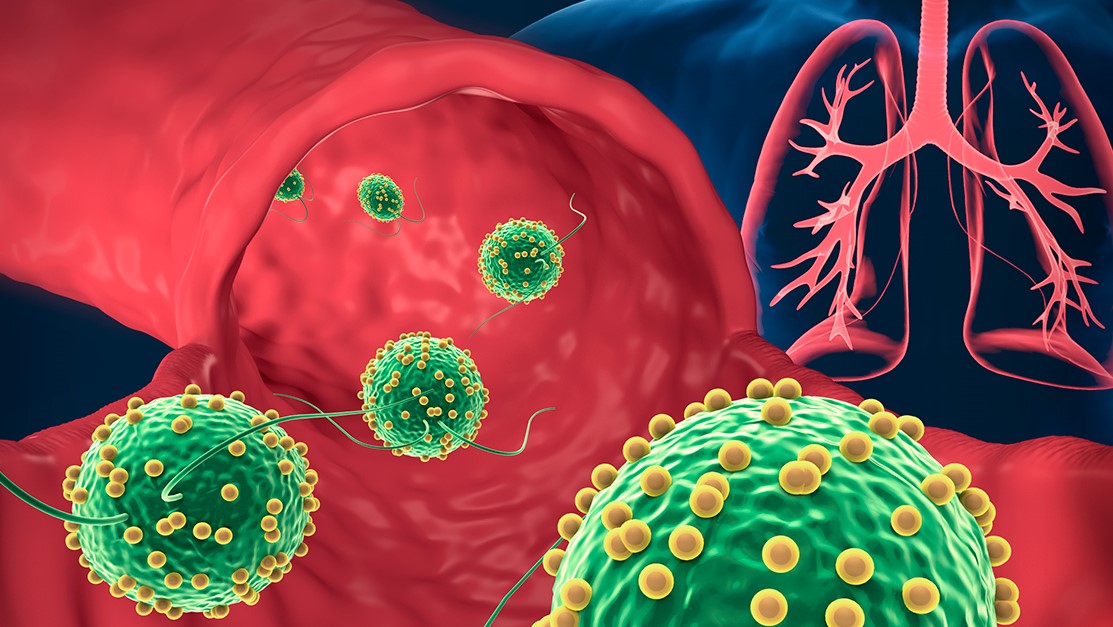

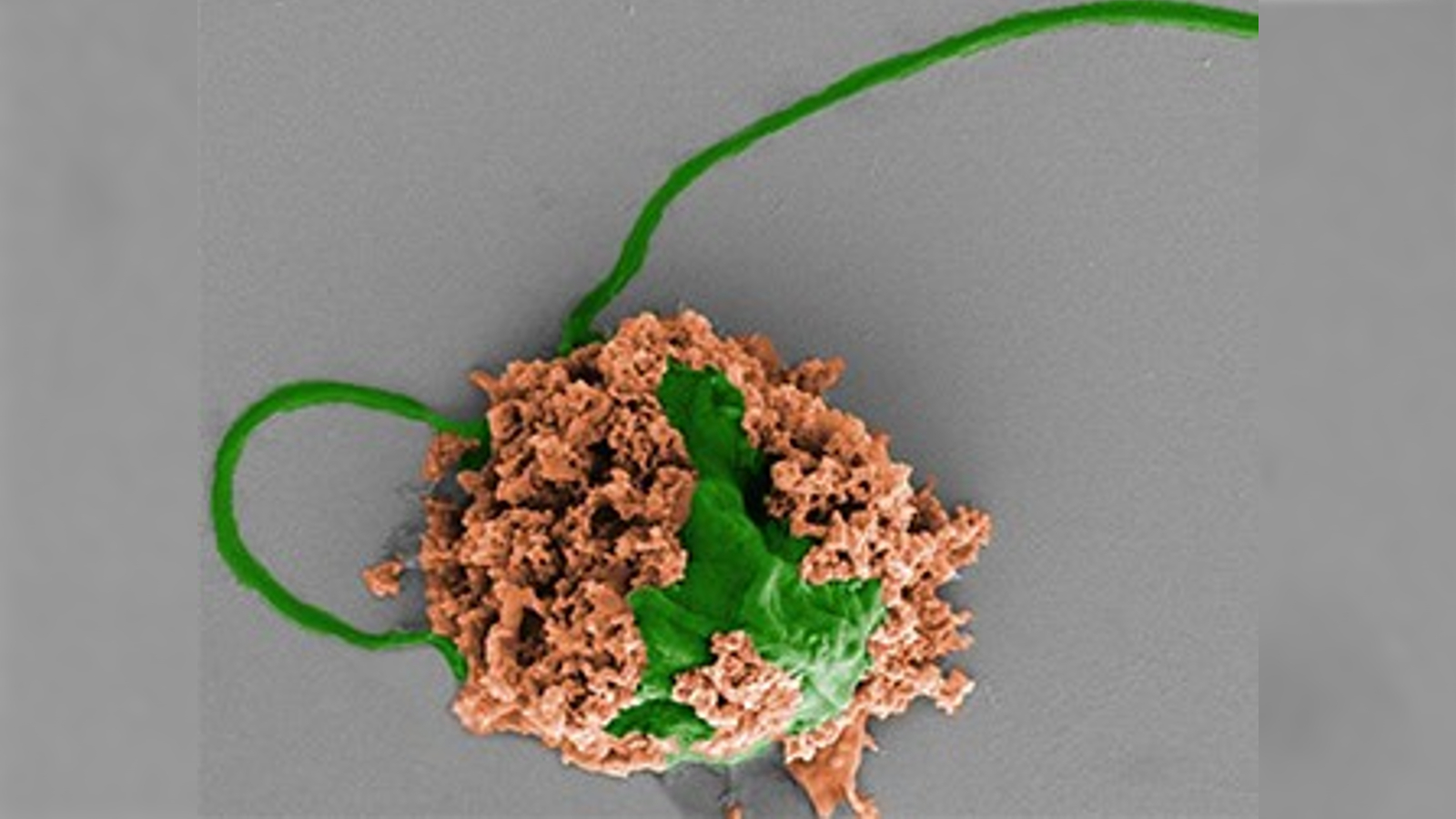

The bacteria-fighting bots are made from living microalgae that have two tails, or flagella, that they use to swim through fluid mediums. Scientists covered the algae in tiny antibiotic-loaded nanoparticles, which slowly secrete the bacteria-killing chemicals throughout the lungs as the algae swim through them.

In the new study, researchers infected two dozen mice with the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which causes pneumonia in a range of animals — including humans. Half of the infected mice were given a dose of microbots and all made a full recovery within a week. But the other half, who were left untreated, all died within three days of being infected.

The experiments are a significant "proof of concept" for the new therapy, which could also be used on humans in the future, researchers wrote in a new paper published online Sept. 22 in the journal Nature Materials.

"Based on these mouse data, we see that the microrobots could potentially improve antibiotic penetration to kill bacterial pathogens and save more patients' lives," study co-author Dr. Victor Nizet, a professor of pediatrics at the University of California San Diego, said in a statement.

Related: Pac-Man-shaped blobs become world's first self-replicating biological robots

During a bacterial pneumonia infection, the invading bacteria cause inflammation in the tiny air sacs, or alveoli, within the lungs, which can also cause these sacs to fill with fluid. The inflammation and fluid can make it extremely difficult and painful to breathe, and can also trigger fevers and chills. Pneumonia can be especially dangerous for young children, old people and patients who are already ill or immune-suppressed, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Targeted delivery

Currently, bacterial pneumonia patients are treated with antibiotics via an intravenous (IV) injection, which delivers the medicine directly into the patient's bloodstream. But it takes time for the antibiotics to work their way through a patient's bloodstream to the lungs, which can be the difference between life and death for a critically ill patient.

By comparison, injecting microbots through the windpipe — whereupon the algae's swimming ability naturally spreads them throughout the rest of the lungs — means that the antibiotics are accurately and quickly delivered to the site of the infection almost immediately. During IV injections, a large proportion of the antibiotics can also end up going to waste, which can reduce the effectiveness of treatments.

"With an IV injection, sometimes only a very small fraction of antibiotics will get into the lungs," Nizet said. "That's why many current antibiotic treatments for pneumonia don't work as well as needed, leading to very high mortality rates in the sickest patients."

In a separate experiment on mice, which compared microbot treatments to IV injections, IV-treated mice required a dose of antibiotics that was 3,000 times greater than the dosage given to microbot-dosed mice, researchers reported in the study.

During extreme cases of pneumonia, patients are often placed on ventilators to help them breathe. This means that many critically ill patients will already have tubes leading directly into their lungs, which could be used to deliver microbots, the researchers noted.

Suppressing symptoms

In addition to being faster and more efficient than current pneumonia treatments, microbots could potentially also help accelerate recovery times for patients by alleviating inflammation as they kill off the pathogens.

IV antibiotics kill off the bacteria causing the disease. After that, patients must wait for the inflammation to recede naturally. Inflammation can leave long-term damage behind, and even when it doesn't, it takes a long time to subside on its own. Bed rest, anti-inflammatories and painkillers can help aid the healing process but tackling the inflammation early on is a better strategy, researchers wrote.

The key to the microbots' anti-inflammatory effect is the nanoparticles that are stuck onto the microalgae. The antibiotic-containing capsules are covered in the cell membranes of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell that is part of the body's natural immune response.

Neutrophils are designed to target inflamed cells and are covered in special structures called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). These NETs are able to trap and neutralize inflammatory molecules released by bacteria, which allows the microbots to mop up these nasty molecules as they swim through the lungs hunting down pneumonia-causing bacteria, according to the statement.

Related: This sideways-scooting robot crab is so tiny it fits through the eye of a needle

Once the microbots have killed off the pathogens, immune cells digest the microbots. Because the microbots are made from completely natural materials, including a special biodegradable polymer that makes up the nanoparticles, there are no leftover chemicals that can cause any damage to the lungs, researchers said.

"Nothing toxic is left behind," study co-author Joseph Wang, a nanoengineer at the University of California San Diego, said in the statement.

Next steps

The new study may only be a proof of concept, but the results show that the microbots are "safe, easy [to administer], biocompatible, and long-lasting," Wang said.

The researchers will now start trials with larger animals to see if the results can be replicated. And if they are, the team hopes to eventually start human trials, according to the statement.

The microbots' ability to swim through the body also makes them great candidates for tackling other ailments, such as stomach and blood infections, the researchers wrote.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus