CRISPR therapy for high cholesterol shows promise in early trial

Using a CRISPR-guided technique called "base editing," scientists edited the genes of liver cells in 10 people's bodies.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A one-time, CRISPR-based gene therapy lowered people's levels of "bad" cholesterol in a small trial, the treatment's maker announced. While the new therapy shows promise, it still has a long way to go before it can be approved for use in patients.

The gene therapy, called VERVE-101, reduced the levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in the blood of people with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), an inherited condition that boosts their LDL levels and their risk of heart disease, according to a statement from Massachusetts-based biotech company Verve Therapeutics, which makes the treatment.

FH is caused by mutations in a key gene that helps control the rate at which the liver clears LDL from the blood. Usually, these mutations change a single building block in the protein encoded by the gene.

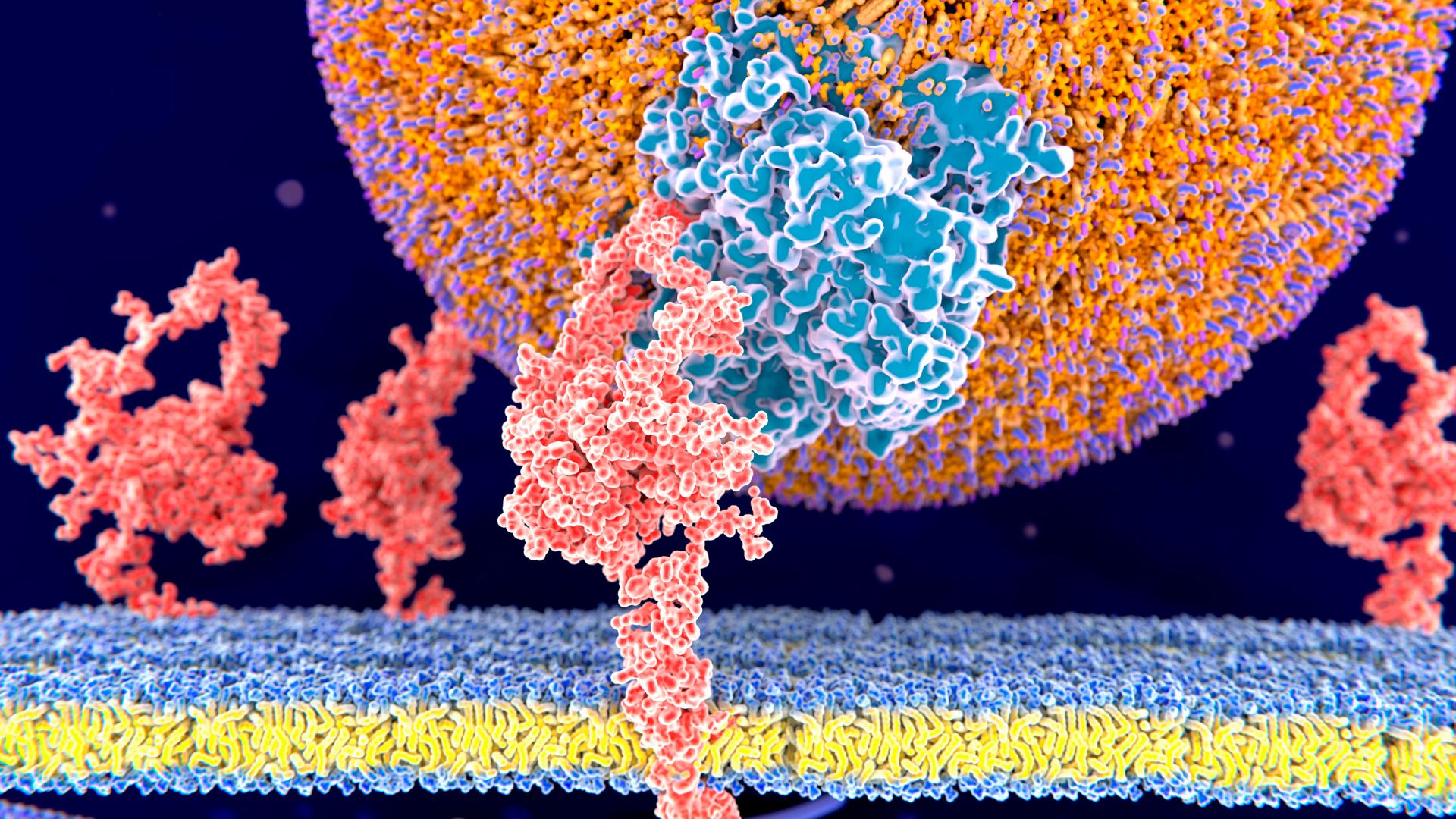

The gene, called PCSK9, essentially works overtime in the context of this disease, and its hyperactivity rapidly breaks down proteins on the surface of liver cells that would normally remove LDL from the bloodstream. As a result, cholesterol levels skyrocket, so people with the disease need cholesterol-lowering medications to keep their levels in check.

Related: CRISPR used to 'reprogram' cancer cells into healthy muscle in the lab

Verve hopes to change this with the new treatment, and on Sunday (Nov. 12), the company released preliminary data from its ongoing clinical trial.

VERVE-101 uses a modified version of CRISPR gene editing, which allows researchers to alter DNA sequences and thus modify gene function. CRISPR gene-editing techniques typically snip through both strands in DNA's twisted double helix and then rely on a cell's repair mechanisms to fix that cut. However, this raises the risk that unwanted mutations will enter the DNA.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By contrast, VERVE-101 uses a different CRISPR-guided approach, called "base editing," which precisely changes just one "letter" in DNA's code, thus cutting the risk of unintentional mutations.

"It is a breakthrough to have shown in humans that in vivo base editing works efficiently in the liver," Gerald Schwank, a gene-editing researcher at the University of Zurich who wasn't involved in the clinical trial, told Science. Plus, it's the first time a base-editing therapy has been administered via infusion, Science reported.

The 10 trial participants treated so far range from 29 to 69 years old, NPR reported. The patients received different doses of VERVE-101. Six people given lower doses showed no response to treatment, while three people in the higher-dose groups saw a drop in LDL. (One person in a higher-dose group is still being monitored and was not included in this initial analysis.)

The high-dose patients' LDL fell by about 39% to 55%, and in the person who saw the largest effect, their LDL stayed low for six months. If VERVE-101 works as intended, the change will be permanent.

Two participants in the trial — one in a low-dose group and one in a high-dose group — experienced severe heart problems. Both had severe underlying cardiovascular disease prior to the trial. The person in the low-dose group died from cardiac arrest weeks after treatment, but the event was deemed unrelated to the gene therapy. Another person had a heart attack the day after treatment, and the event was "considered potentially related to treatment due to the proximity to dosing," Verve reported.

Beyond these cardiovascular events, there's some additional safety concerns around whether base editing could have "off-target" effects in genes that it's not intended to edit, Nature reported.

"This is a gene editing study — you are changing the genome forever," Dr. Karol Watson, a UCLA cardiologist who was involved in the trial, said at a news conference, according to Nature. "Safety is going to be of the utmost importance, especially because there are currently safe and efficacious strategies available for lipid lowering."

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus