'Real-life dragon' in Cretaceous Australia was huge, toothy and a 'savage' hunter

Thapunngaka shawi was Australia's biggest known pterosaur.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 110 million years ago in what is now Australia, a flying "dragon" dominated the skies. With an estimated 23-foot (7 meters) wingspan, it was the continent's biggest pterosaur, new research finds.

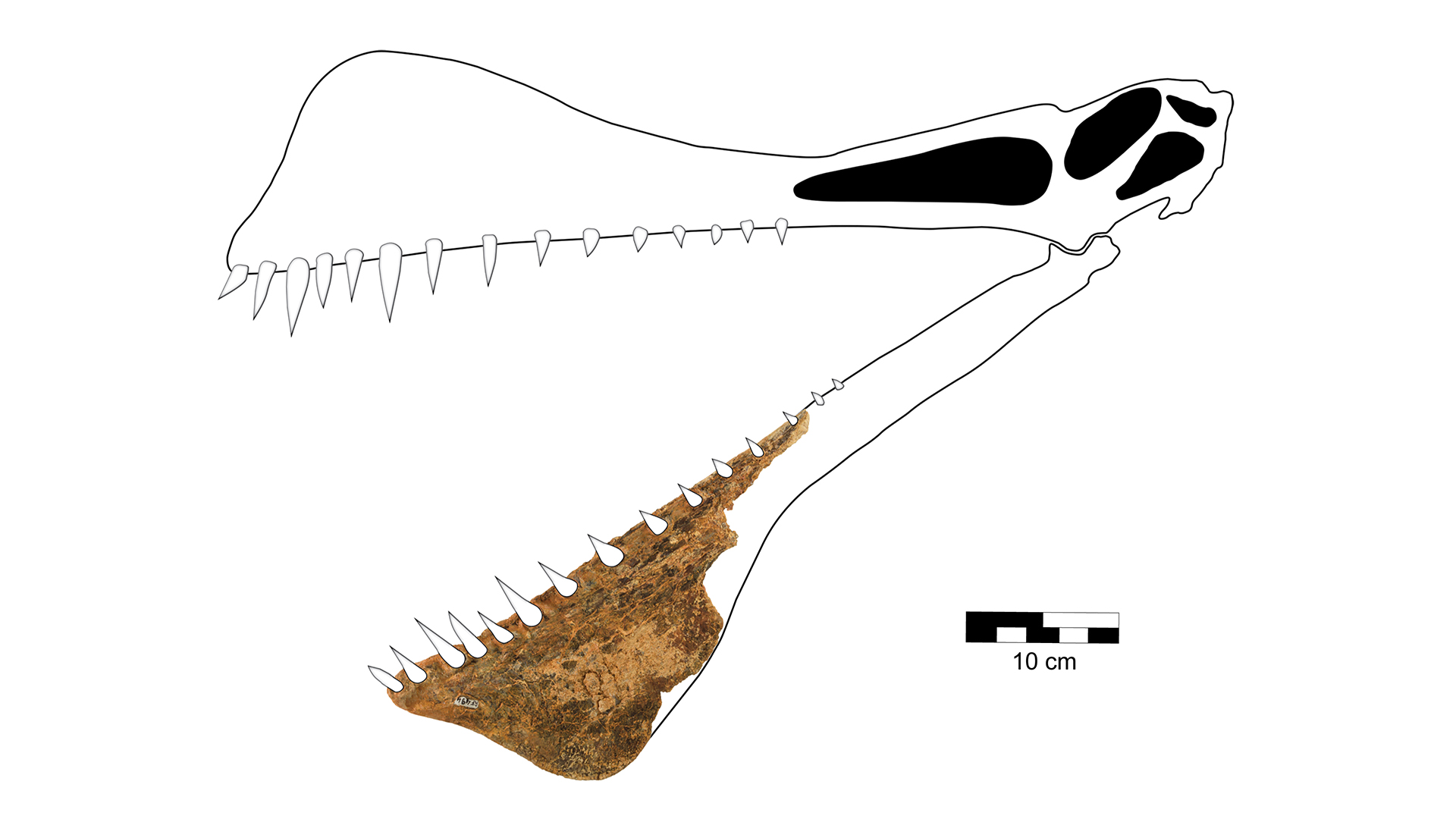

Pterosaur fossils are rare in Australia; fewer than 20 specimens have been described since paleontologists found the continent's first pterosaur bones about two decades ago. Scientists identified the newfound species, Thapunngaka shawi, from a fossilized piece of a lower jaw found at a site in North West Queensland dating to the Cretaceous period (about 145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago).

T. shawi's skull would have measured over 3 feet (1 m) long, and its mouth would have been crammed with approximately 40 teeth, making the extinct reptile "the closest thing we have to a real life dragon," study lead author Tim Richards, a doctoral candidate and researcher in The University of Queensland (UQ) Vertebrate Palaeontology and Biomechanics Lab, said in a statement.

Related: Photos of pterosaurs: Flight in the age of dinosaurs

The pterosaur's genus name, "Thapunngaka," comes from one of the languages spoken by the Indigenous people of the Wanamara Nation, who live where the fossil was discovered. The name incorporates "thapun [ta-BOON'] and ngaka [NGA'-ga]," which are "the Wanamara words for 'spear' and 'mouth,' respectively," the researchers wrote. "Shawi," the species name, is a nod to the man who found the fossil, an amateur prospector named Len Shaw.

"So the name means 'Shaw's spear mouth,'" the scientists wrote in the study.

The spear-mouthed pterosaur had a crest on the underside of its lower jaw, and its upper jaw was likely crested, too, according to the study. Toothed pterosaurs called anhanguerians had such skull crests, and the researchers classified T. shawi as part of that group.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"These crests probably played a role in the flight dynamics of these creatures," study co-author Steven Salisbury, a senior lecturer in the UQ School of Biological Sciences, said in the statement.

The scientists also counted tooth sockets in the jaw fragment, and determined that the pterosaur would have had at least 26 teeth in its lower jaw and up to 40 teeth in total.

When T. shawi was alive, about 60% of the Australian continent would have been underwater, covered by shallow seas. Though the T. shawi fossil was a rare find, paleontologists had previously found numerous fossils of marine invertebrates — such as mollusks, snails and ammonites — at the Queensland site, as well as fossils of vertebrates, like sharks and other fishes, and plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs (extinct marine reptiles). While the flying Cretaceous "dragon" T. shawi probably wasn't big enough to carry off a plesiosaur, it likely was a swift and deadly predator, swooping down to scoop up fish from the water or to nab small prey on land, Richards said in the statement.

"It would have cast a great shadow over some quivering little dinosaur that wouldn't have heard it until it was too late," Richards said. "This thing would have been quite savage."

The findings were published Aug. 9 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus