The 10 Biggest Science Stories of the Decade

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Given the rapid pace of change in technology and science, it can be easy to forget what we didn't know just a few short years ago. The past decade has seen breakthroughs in physics, biology and astronomy, to name just a few. Which of these discoveries are the most important is probably for historians to judge, but some of the consequences of the discoveries early in the decade are beginning to reverberate. Here are our picks for the decade's biggest scientific advances and surprising discoveries.

2010: The First Synthetic 'Life'

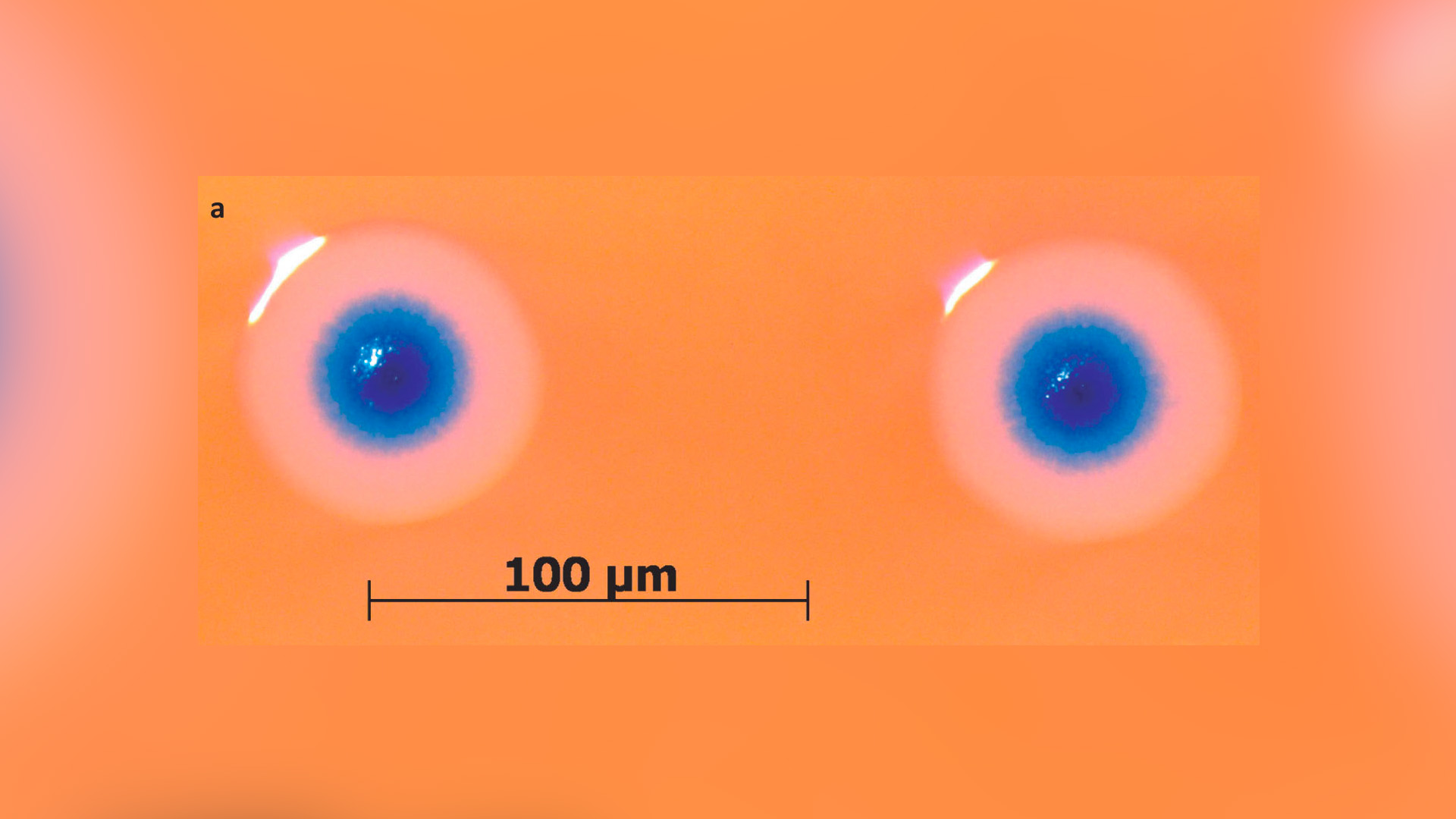

Scientists blurred the line between natural and man-made in 2010 with the creation of the first-ever organism with a synthetic genome. Scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute assembled the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma mycoides out of more than a million base pairs of DNA. Then, they inserted this human-engineered genome into another bacterium, Mycoplasma capricolum, which had been emptied of its DNA. The M. capricolum's machinery soon began to translate the instructions of this synthetic genome into action, reproducing just as M. mycoides would.

Since this breakthrough, scientists have continued to make advances in synthetic biology. In 2016, scientists built the smallest synthetic microbe yet, with just 473 genes. In 2017, they announced the creation of five synthetic yeast chromosomes; the plan is to replace all of the 16 chromosomes in yeast with synthetic chromosomes that could be tweaked to perform certain tasks, such as mass-producing antibiotics or even creating lab-grown meat.

2011: HIV Preventative Treatment

Today, many people at high risk for contracting the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS, pop a daily pill to reduce their risk. In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a medication, called Truvada, for this purpose. But it was a large study released in 2011 that set the stage for this sea change in HIV prevention.

That study, which the journal Science dubbed the "breakthrough of the year," was the first since 1994 to show a new way to prevent HIV transmission from one person to another. (In 1994, researchers reported that they'd found a pharmaceutical option to help prevent the transmission of HIV from a pregnant woman to her fetus.) The study began in 2005, and the 2011 findings were interim results. The researchers found a 96% reduction in HIV transmission in that data. The final data encompassing the entire 10-year study, reported in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2016, showed a 93% reduction in HIV transmission.

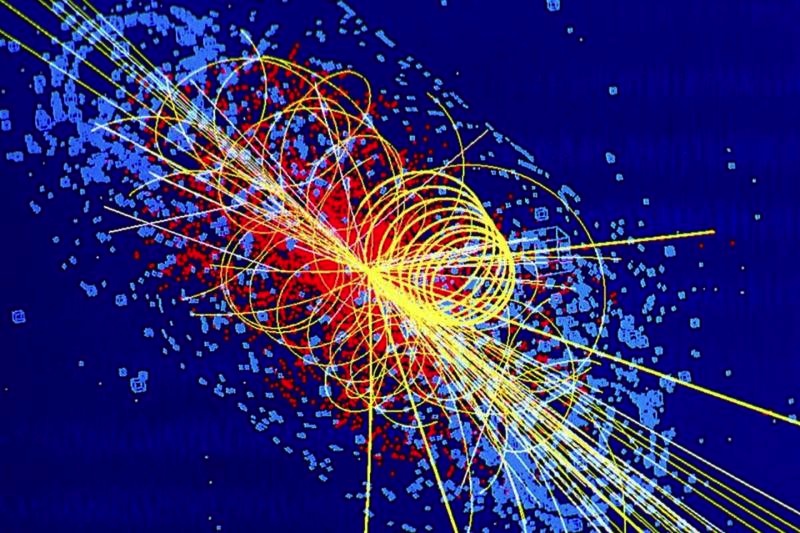

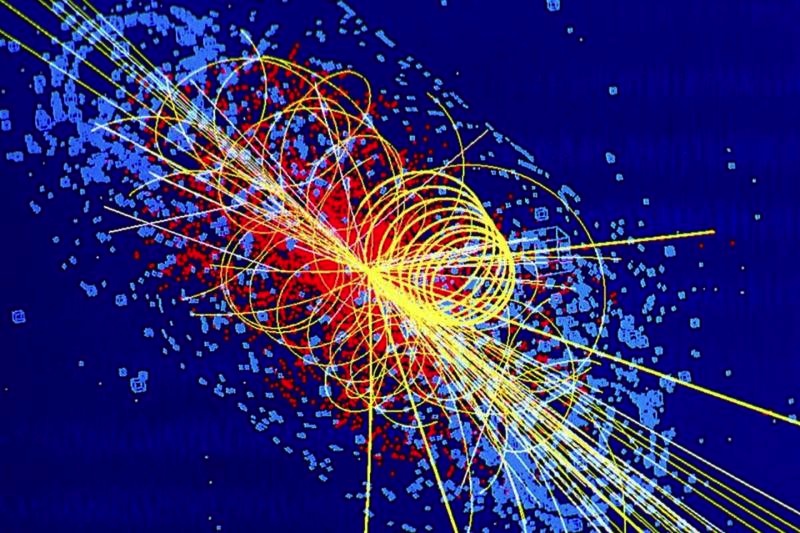

2012: Higgs Boson

In July 2012, scientists working at the world's largest particle accelerator announced that they'd hit pay dirt. Experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) had, at long last, uncovered evidence of the last undiscovered particle predicted by the Standard Model of physics.

The Higgs boson had been found. This is the particle associated with the Higgs field, an energy field at the root of why particles have mass. Particles gain mass by slogging across this three-dimensional field, creating tiny disturbances in the field. (The stronger their interactions with the field, the more mass they have.) When the field experiences a major energy flare-up in a particular spot, it emits a Higgs boson. In 2013, physicists confirmed that their 2012 observations were indeed the elusive particle, sometimes called the "God particle" because of its role in giving all other particles mass.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The discovery of the Higgs raised new questions for physicists. The particle was a bit lighter than some of its interactions with other elementary particles would have predicted, meaning that either someone goofed up on the math or there's more than one type of Higgs — perhaps including a heavier Higgs that hasn't been discovered. Physicists are now using the LHC to search for these possible heavy Higgs.

Lucas Taylor/CMS

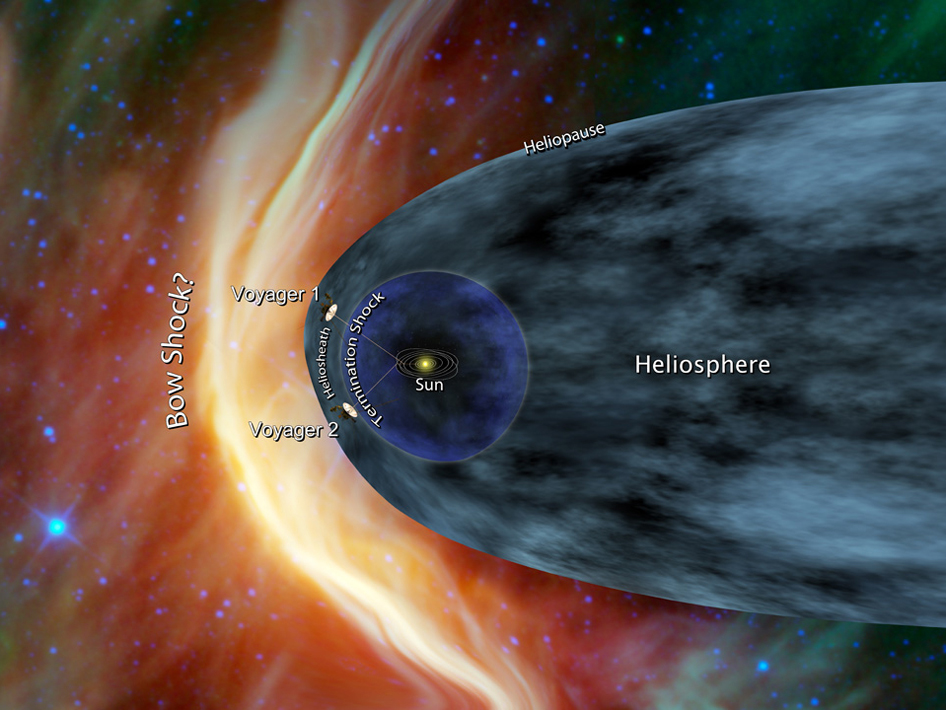

After nearly 35 years of zinging past planets and moons, NASA's Voyager 1 probe made history in 2013, when scientists announced that the spacecraft had officially left the solar system in August 2012.

The probe was launched from Earth in 1977 and spent the next decade exploring Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and their moons. In 2013, data sent back from the probe suggested changes in electron density around Voyager 1 — a major clue that the spacecraft had left the bounds of the solar system. Voyager 1 will continue to send information back to Earth about interstellar space until about 2025. After that, it's set for a long, quiet retirement in deep space, with the possibility that maybe, someday, some alien life-form will notice the little probe and its golden record, a time capsule that holds images of people, maps of our solar system and other clues to the existence of civilization on Earth.

2014: Gravitational Waves

Before 2014, scientists had only indirect evidence of the Big Bang, the theory that describes a mind-boggling expansion of space that occurred 13.8 billion years ago and gave birth to our universe. But in 2014, for the first time, scientists observed direct evidence of this cosmic expansion, what some called a "smoking gun" for the beginning of the universe.

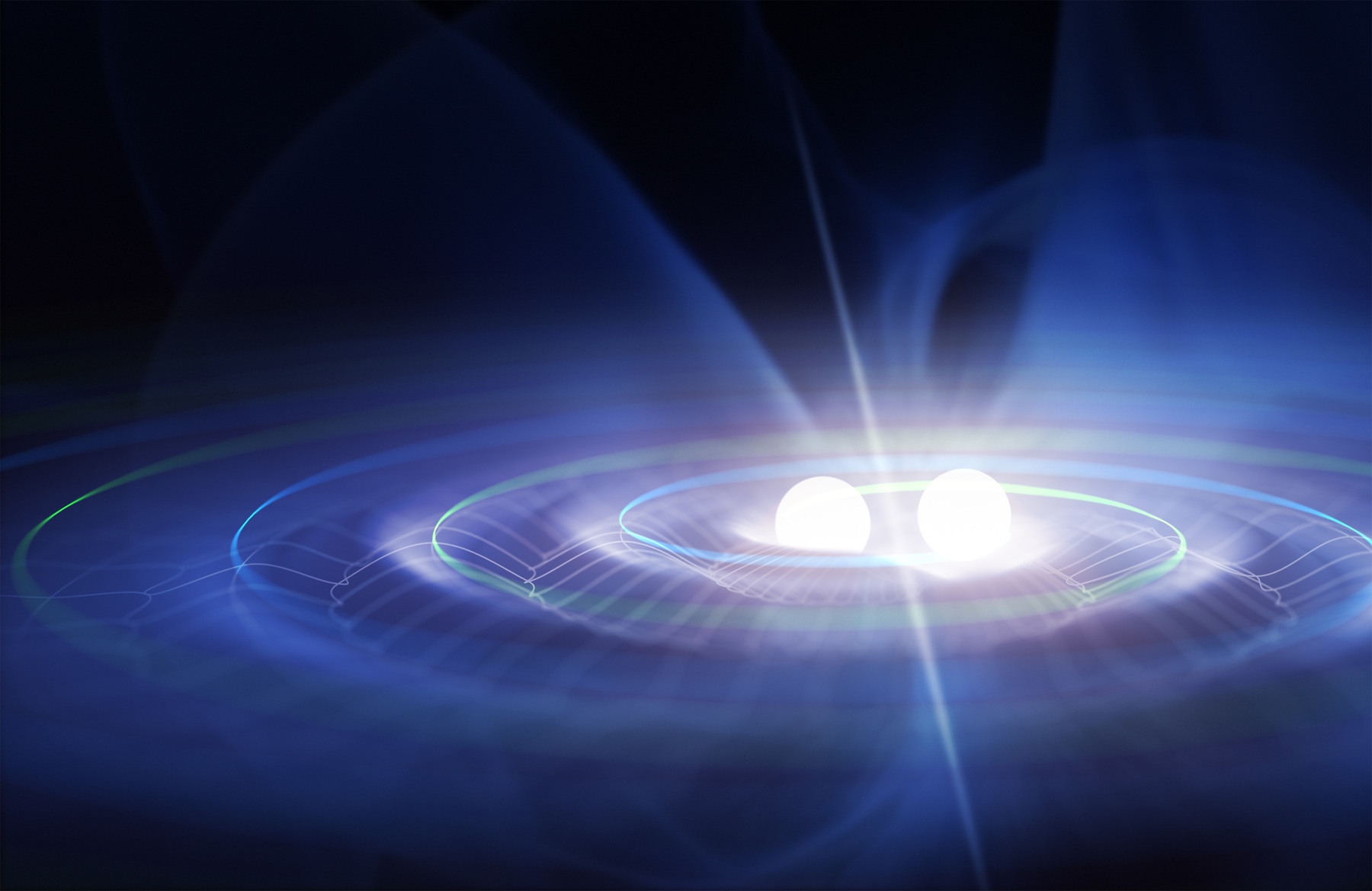

This evidence came in the form of gravitational waves, literal ripples in space-time left over from the first fraction of a second after the Big Bang. These ripples generated changes in the polarization in the cosmic microwave background, which is radiation left over from the early universe. The polarization changes are called B-modes. It was these B-modes that scientists detected using the Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization 2 (BICEP2) telescope in Antarctica.

Since then, gravitational waves have continued to reveal mysteries of the universe, such as the dynamics of the collisions of black holes and crashes between neutron stars. Gravitational waves may even help to finally pin down just how fast the universe is expanding.

2015: First CRISPR editing of human embryos

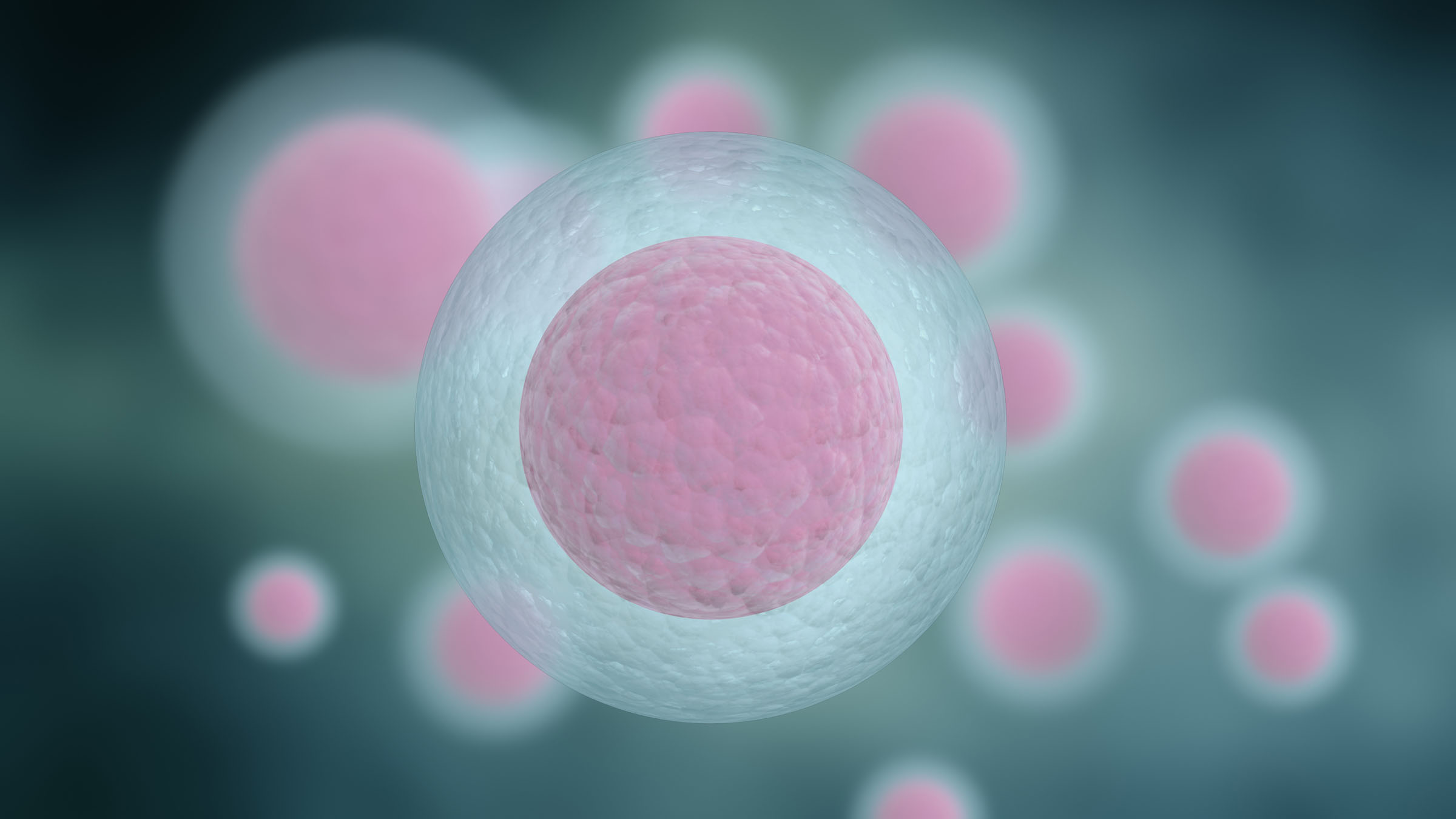

Possibly the biggest biomedical story of the decade is the emergence of a gene-editing technology called CRISPR from relative obscurity. This technology arises from the natural defense mechanisms of some bacteria; it's a series of repetitive gene sequences tied to an enzyme called Cas9 that acts like a pair of molecular scissors. The gene sequences can be edited to put a bull's-eye on a particular segment of DNA, directing the Cas9 enzyme to go in and start snipping.

Using this system, scientists can easily erase and insert bits of DNA in living organisms, an ability with obvious implications for curing genetic diseases — and possibly leading to custom-made babies. The first step along this potential road was taken in 2015, when scientists at Sun Yat-sen University in China announced that they'd made the first-ever genetic modifications to human embryos using CRISPR. The embryos weren't viable, and the procedure was only partially successful — but the experiment was the first to push an ethical line that the scientific community is debating to this day.

2016: Exoplanet Discovered in a Habitable Zone

Earth's closest exoplanet neighbor, discovered in 2016, is not only a mere 4.2 light-years away — it has the potential to host life.

That doesn't mean that the planet, dubbed Proxima b, is sure to be habitable, but it resides in the habitable zone of its star, meaning it orbits its star at a distance that would allow liquid water to exist on the planet's surface. The planet orbits Proxima Centauri; wobbles in that star's movements as the planet passed by hinted atProxima b's existence.

Since the discovery, scientists have observed high-radiation superflares from Proxima Centauri blasting the exoplanet, drastically reducing the chances that life could survive on Proxima b. However, they've also found that there may be more planets orbiting near Proxima b.

2017: Oldest Homo sapiens fossils push species back 100,000 years

How long has Homo sapiens roamed the planet? A discovery announced in 2017 pushed the timing back to 300,000 years.

That's 100,000 years longer than had previously been believed. Researchers found the 300,000-year-old bones in a cave in Morocco, where at least five individuals may have taken shelter during a hunt. The discovery site — in northern Africa, not eastern Africa, where the previous oldest Homo sapiens fossils were found — hints that our species may not have evolved first in eastern Africa and then later radiated elsewhere. Instead, Homo sapiens might have evolved all across the continent.

2018: First living CRISPR babies

A mere three years after the first editing of nonviable human embryos with CRISPR, someone crossed another gene-editing line. This time, a Chinese scientist named Jiankui He announced that he'd edited the genomes of two embryos that were then implanted via IVF (in vitro fertilization) into the mother’s womb and born: twin girls who are the world's first CRISPR babies.

The edit he made was to a gene called CCR5 — a change that, theoretically, should make the children less vulnerable to contracting HIV. Many scientists were appalled that He would take the step of gene editing in this context, particularly given the available and less technologically intense methods of avoiding HIV (such as preventive antiretroviral treatment). Later, data released by the researchers suggested that they'd actually induced a previously unknown mutation in the girls rather than reproducing a known mutation.

The potential side effects for the girls are still unknown, as is the fate of the scientist who did the editing. In January 2019, the The New York Times reported that He was likely to face criminal charges in China, though it was unclear under what laws he could be charged.

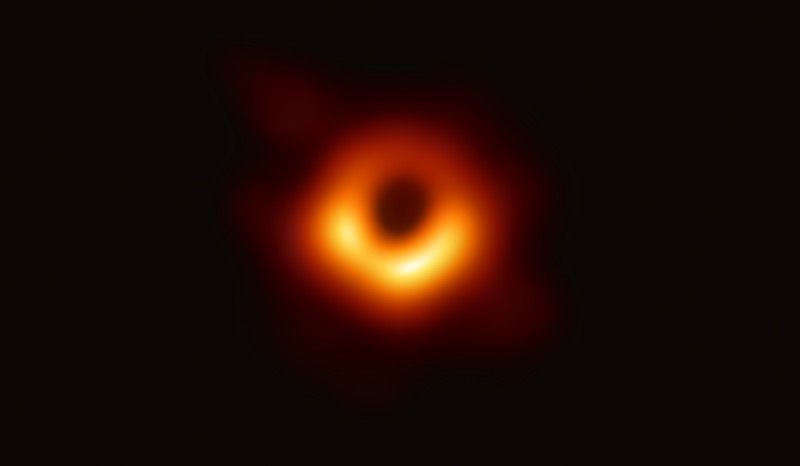

2019: First Black Hole Image

Black holes have always been an astronomical fascination: We know they're there, but because light can't escape from beyond their event horizons, they're also sort of invisible.

Until this year: For the first time, scientists captured an image of a black hole. The portrait subject was black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy that is as wide as our entire solar system. The picture looks like a glowing doughnut of matter surrounding an abyss of blackness; this is the dust and gas orbiting the black hole's point of no return. The discovery earned the researchers involved the 2020 Breakthrough Prize, one of the most prestigious awards in science. They're now working to capture not just images, but movies, of black holes.

- The 10 Strangest Animal Stories of 2019

- 16 Times Antarctica Revealed Its Awesomeness in 2019

- 10 Times Nature Was Totally Metal in 2019

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus