Ancient 'Tully monster' was a vertebrate, not a spineless blob, study claims

An odd carboniferous creature with eyes like a hammerhead was this: a vertebrate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

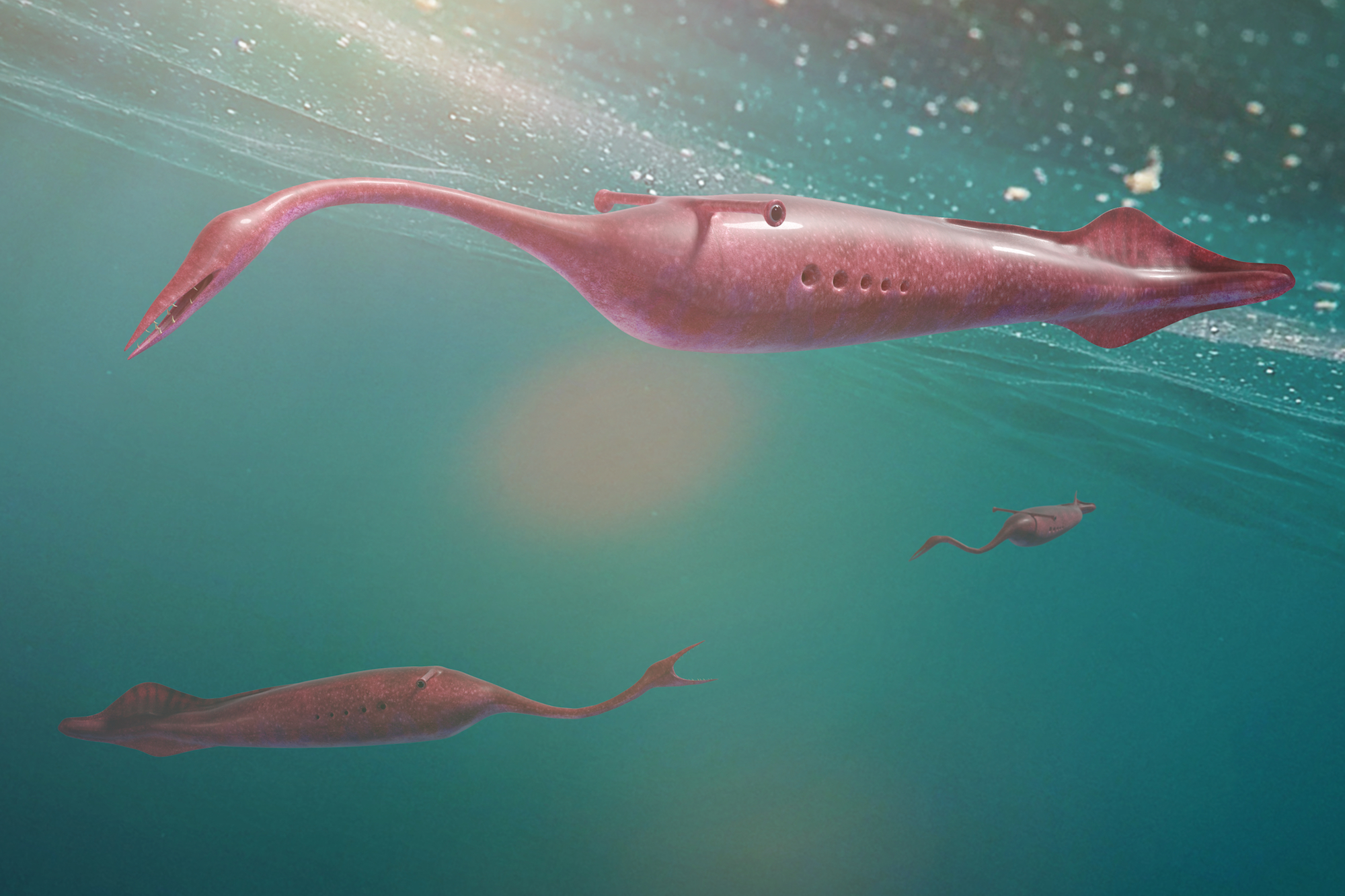

There are few ancient creatures as controversial as the Tully monster, a bowling-pin-sized oddity with eyes like a hammerhead that lived about 307 million years ago. Now, after decades of studies, each with a different take on how to define the weird aquatic creature, the Tully monster has been decoded: It's a vertebrate, meaning it had a backbone, a new study finds.

Scientists analyzed the chemical residues left on fossilized remains of the Tully monster (Tullimonstrum gregarium) and compared them with the chemical remnants on other vertebrate and invertebrate fossils from the monster's ancient home in what is now Mazon Creek in northeastern Illinois, said study lead researcher Victoria McCoy, a visiting assistant professor of geosciences at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

McCoy and her colleagues took a "chemical approach" rather than looking at the Tully monster's fossilized anatomy, which is "kind of like a Rorschach test," McCoy told Live Science. Ever since amateur fossil collector Francis Tully discovered the monster's remains in 1958, researchers looking at the anatomy have interpreted the beast to be all kinds of things, including a vertebrate, an invertebrate, a shell-less snail, a type of worm, a jawless fish and an arthropod, or a member of a group that includes insects, spiders and lobsters.

Related: Photos: Ancient Tully monster's identity revealed

"Due to all the back and forth, we thought that maybe just investigating the [anatomy] would never be enough to end the debate," McCoy said. "We decided then to go look at the chemistry of the Tully monster fossils to understand what the different tissues were made of."

To determine whether the Tully monster was a vertebrate or invertebrate, the team decided to see if its fossils held the remnants of chitin, a long string of sugar molecules which makes up the "harder, crunchier tissues" in the exoskeletons and teeth of invertebrates, or the remnants of proteins that make up the keratin and collagen found in vertebrates, McCoy said.

The scientists used "in situ Raman microspectroscopy," which is a nondestructive method (meaning it doesn't harm the fossil) that involves shooting a laser at the specimen. The laser's energy causes the different chemical bonds within the specimen to vibrate, each at their own unique rate. By graphing these rates, scientists can determine what kinds of compounds are present.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's extremely difficult to identify one compound," McCoy said. "But, as long as you know what classes of compounds make up those in your sample, that's enough to distinguish vertebrates from invertebrates."

The team looked at 32 different spots on 20 fossils, including three Tully monster specimens and 17 other ancient animals. The results revealed that Tully had a backbone, she said.

"The Tully monsters, all of its tissues that we analyzed, were made up of proteins and none of them were made up of chitin," McCoy said. "So, that is really strong evidence that the Tully monster was, in fact, a vertebrate."

This finding jibes with a 2016 study in the journal Nature by the same team, which suggested that the Tully monster was a jawless fish in the same lineage as the modern-day lamprey.

However, this study isn't the final word on the Tully monster's true identity, two researchers who were not involved with the new study told Live Science.

Related: Photos: Ancient marine critter had 50 legs, 2 large claws

For instance, the interpretation of Raman spectra of complex geological material "is not straightforward. This is why the authors use statistical methods to tease apart the differences in Raman spectra," Shuhai Xiao, a professor of geobiology at Virginia Tech, told Live Science in an email.

However, Xiao added that gathering and analyzing Raman spectroscopy data "can potentially provide new insights into the study of problematic fossils, such as Tully monster."

It would have been helpful if the analysis had included more specimens, both of Tully monsters and other equally ancient animals from Mazon Creek, Steven Jasinski, the paleontologist at the State Museum of Pennsylvania, told Live Science. However, "their results are good and I think it definitely is suggestive that Tully monster is a vertebrate. I just don't think it's the endpoint."

"I think more study will have to go in to confer or refute their results," said Jasinski, who was not involved in the current study. "But I definitely think it's a step toward seeing the Tully monster might be a really weird, abnormal vertebrate."

The study was published online April 28 in the journal Geobiology.

- Image gallery: 25 amazing ancient beasts

- Photos: These animals used to be giant

- Image gallery: Bizarre Cambrian creature

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus