A Sunken Soviet Sub Is Raising the Radioactivity of the Norwegian Sea 800,000-Fold. But Don't Worry.

A Cold War Soviet nuclear submarine met disaster 30 years ago when it sank in the Norwegian Sea, leading to the deaths of 42 sailors. But instead of lying peacefully at the bottom of the sea, that sub, called the Komsomolets, is leaking radioactive material deep beneath the waves.

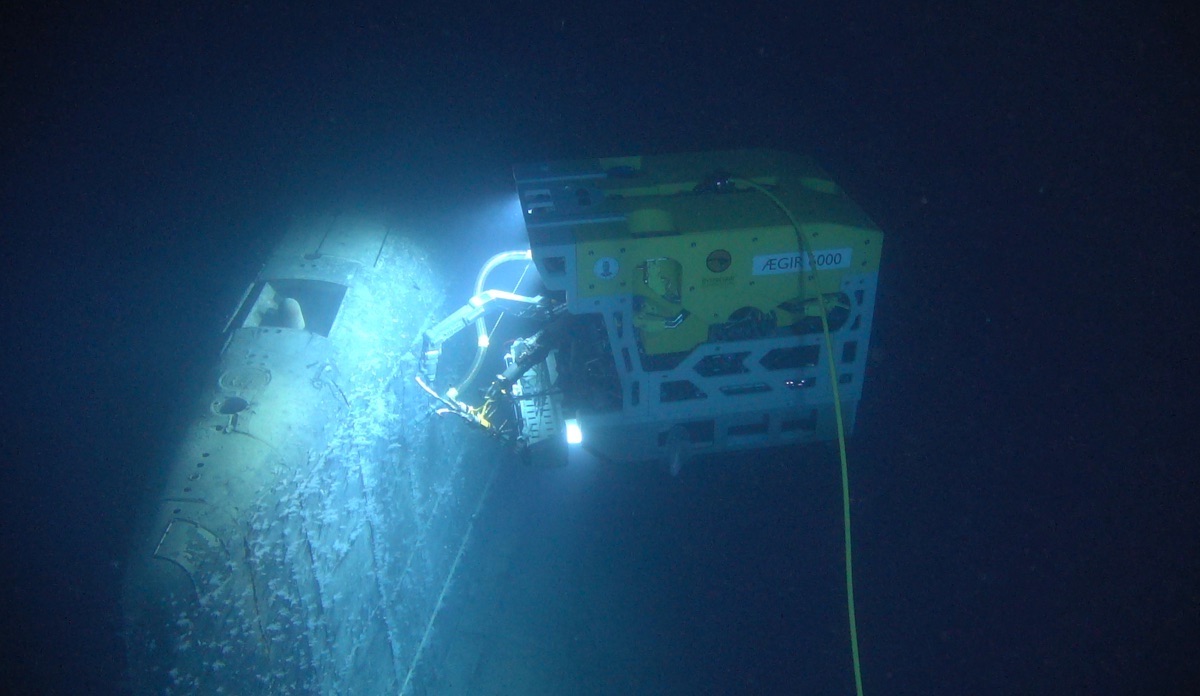

Several samples collected by an underwater robot from and around the sunken sub's ventilation duct show that it's leaking high levels of cesium, a radioactive element, according to the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (IMR). Some of the cesium levels are 800,000 times higher than normal levels in the Norwegian Sea, according to the institute.

However, this radiation does not pose a risk to people or fish, the IMR noted. [Photos: WWII Shipwrecks Found Off NC Coast]

The Soviets launched the 400-foot-long (120 meters) Komsomolets, which means "member of the Young Communist League," in May 1983, according to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. While the Komsomolets was on patrol in April 1989, a fire broke out on board, leading to the sub's eventual demise. As the Komsomolets sank, its two nuclear reactors and at least two torpedoes with plutonium-containing nuclear warheads fell to the bottom of the sea.

Since then, the Russians and Norwegians have monitored the wreck, noting its radioactive leaks.

"We took water samples from inside this particular duct because the Russians had documented leaks here both in the 1990s and more recently in 2007," Hilde Elise Heldal, the expedition leader, said in the IMR statement. "So we weren't surprised to find high levels here."

An analysis showed that one sample had 100 becquerels per liter, compared with the usual 0.001 becquerels per liter normally found in the Norwegian Sea. (A becquerel (Bq) is a unit of radioactivity that represents decay per second.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Heldal said it was important to put this number into perspective. For instance, following the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, regulations were set for how much cesium would be allowed in foods. "After the Chernobyl accident in 1986, Norwegian authorities set this limit to 600 Bq/kilogram," she said. So, even though the cesium levels from parts of the submarine "were clearly above what is normal in the oceans," they still "weren't alarmingly high," Heldal said.

Moreover, samples taken a few yards from the duct didn't have any measurable levels of cesium in them. "We didn't find any measurable levels of radioactive cesium there, unlike in the duct itself," Justin Gwynn, a researcher at the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority, said in the statement.

Strange cloud

But the remotely operated vehicle (ROV), called the Aegir 6000, did catch a strange sight on film: an eerie cloud emanating from the submarine's duct. After detecting the cloud, the ROV took a sample, which was later found to contain high levels of cesium.

Then, the ROV took another sample from a cloud seen rising from a nearby grille. This reading also had high radioactivity levels.

Now, the researchers are wondering if this "cloud" is related to the high radioactivity levels in those areas. "It looks very dramatic on video, and it's definitely interesting, but we don't really know what we're seeing and why this phenomenon occurs," Gwynn said. "It's something we want to find out more about." [Photos: WWI-Era German Submarine Wreck Discovered Off Scotland Coast]

The researchers plan to study the many samples the ROV collected from the submarine. In the meantime, Heldal stressed that seafood eaters have little to worry about.

"What we have found during our survey has very little impact on Norwegian fish and seafood," she said. "In general, cesium levels in the Norwegian Sea are very low, and as the wreck is so deep, the pollution from Komsomolets is quickly diluted."

Even so, scientists plan to monitor the vessel for years to come, especially since it's the only known source of radioactive pollution in Norway's waters.

"We need good documentation of pollution levels in seawater, seabed sediments and, of course, fish and seafood," Heldal said. "So, we'll continue monitoring both Komsomolets in particular and Norwegian waters in general."

- In Pictures: Japan Earthquake & Tsunami

- Image Gallery: Stunning Shots of the Titanic Shipwreck

- In Photos: WWII-Era Shipwrecks Illegally Plundered in Java Sea

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.