Before There Were Dinosaurs, This Triassic 'Lizard King' Ruled Antarctica

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This ancient reptile was an archosaur — part of the same group that would later include dinosaurs, pterosaurs and crocodilians. Scientists recently discovered a partial skeleton of the lizard dating to 250 million years ago, a time when Antarctica was bursting with plant and animal life.

Not only does the fossil of this former "king" provide a sharper picture of the forest landscape in long-ago Antarctica, it also helps to explain the evolutionary landscape following the biggest mass extinction in Earth's history, scientists reported in a new study. [Antarctica: The Ice-Covered Bottom of the World (Photos)]

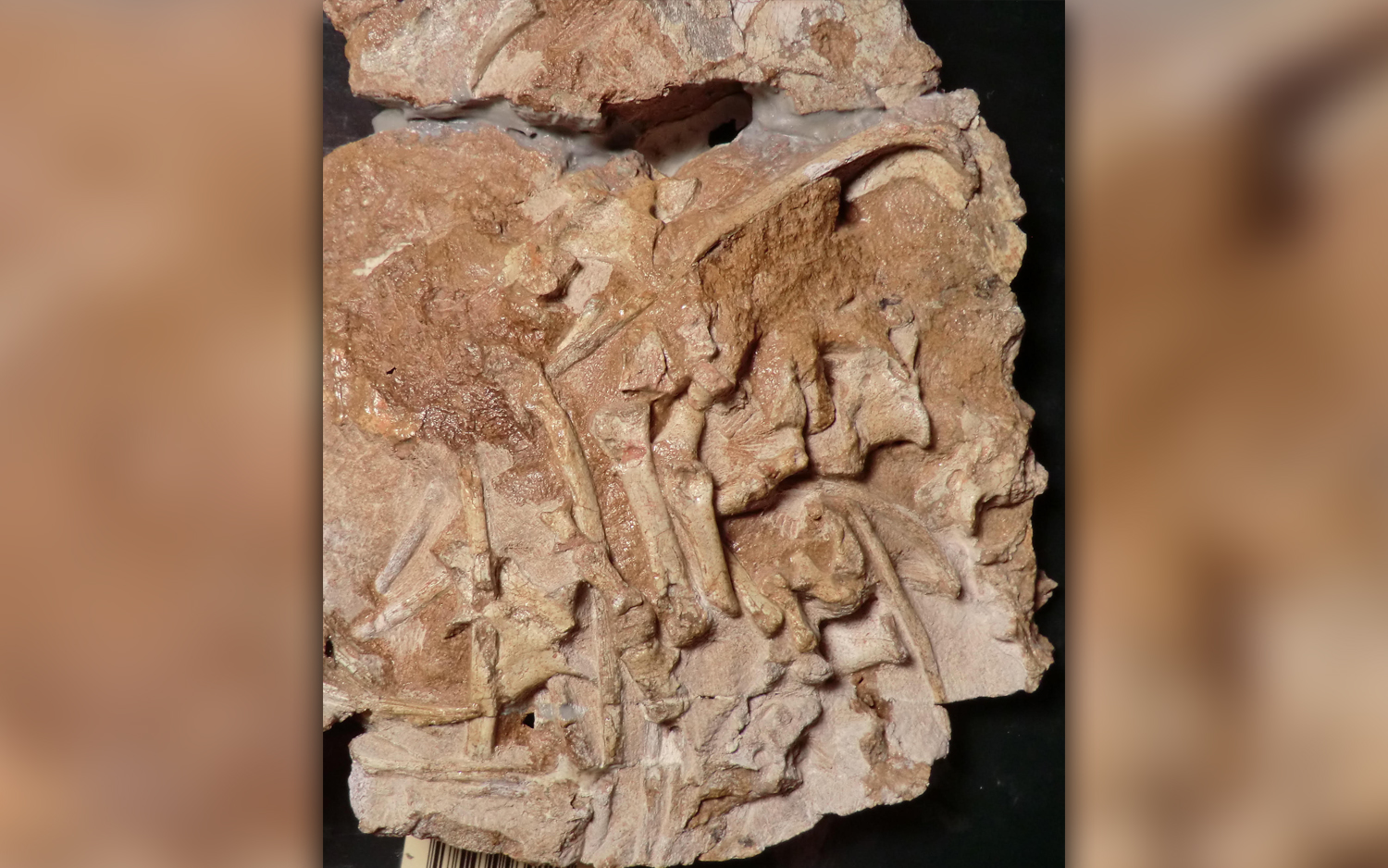

Though the lizard fossil was incomplete, researchers were able to tell from the fused vertebrae that the animal was an adult reptile, and it likely measured about 4 to 5 feet (1.2 to 1.5 meters) in length. They dubbed it Antarctanax shackletoni: The first part of its name comes from the Greek words for "Antarctic king;" the second part is a nod to pioneering British polar explorer Ernest Shackleton, who named the Beardmore Glacier — where many Antarctic fossils, including Antarctanax, have recently been found — following an expedition in 1908.

Subtle features in the bones of the lizard's spine and feet indicated that it was a new species, and its foot shape suggested that it lived on the ground, scampering over the forest floor, lead study author Brandon Peecook, a Meeker Postdoctoral Fellow at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, told Live Science.

"It doesn't have any adaptations in its feet that would make us think it lived in the trees or that it's a burrower," Peecook said.

"Widespread forests"

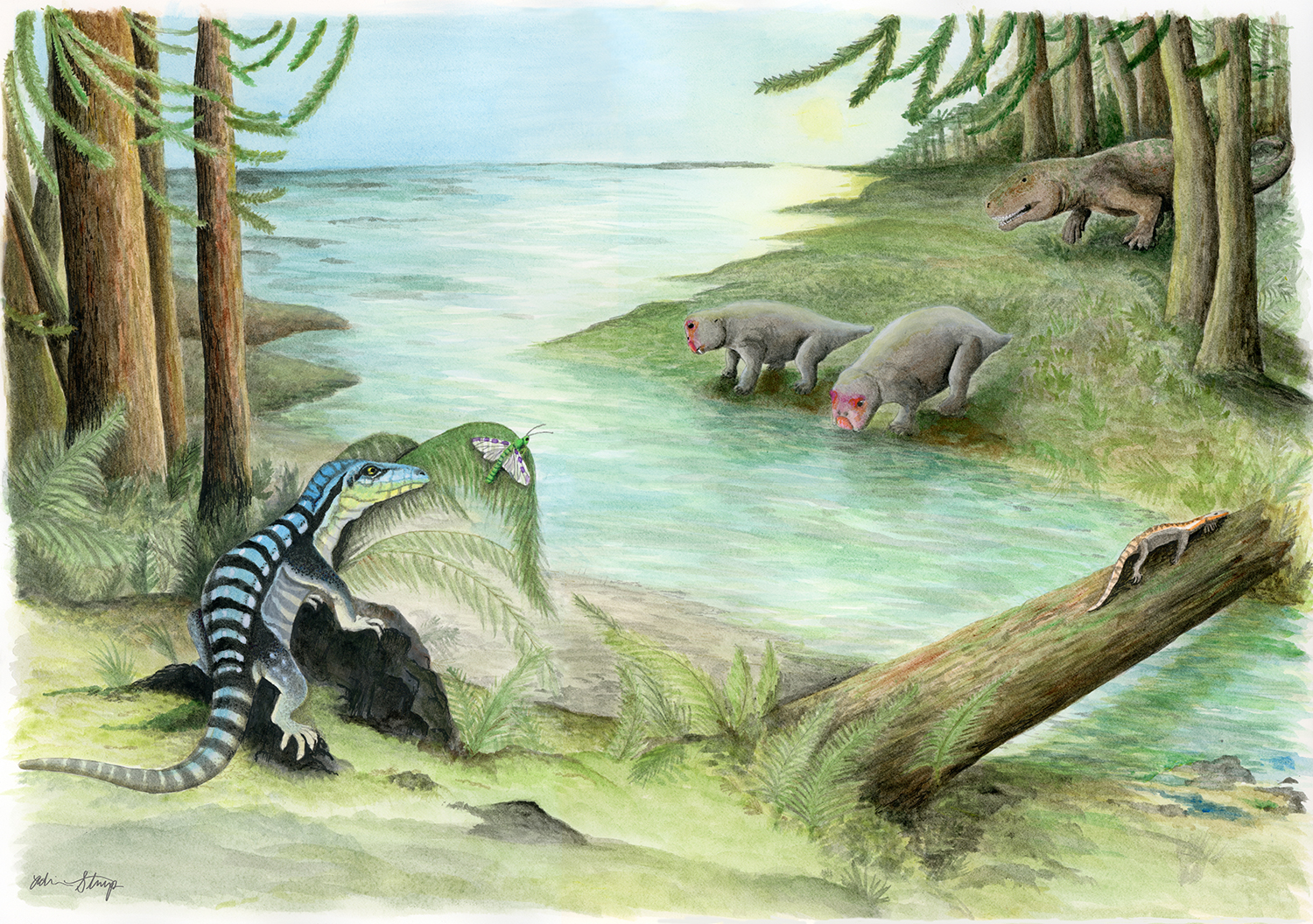

Those trees might be hard to picture if you imagine Antarctica as it is today: a frozen, mostly lifeless, ice-covered desert. But hundreds of millions of years ago, Antarctica hosted a warm, wet environment where temperatures rarely — if ever — dipped below freezing, the study authors reported.

"We have evidence of widespread forests all over the place, and big rivers moving through those forests," Peecook said. Roaming among the trees and rivers were amphibians, mammal relatives called cynodonts, other mammal-like predators called dicynodonts that had tusks and beaks, and reptiles like Antarctanax, he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But this fossil also contributes to an important evolution story. With the discovery of this previously unknown ancient reptile, researchers are piecing together the unexpected archosaur diversity that arose shortly after the Permian mass extinction — a cataclysmic event about 252 million years ago that wiped out around 96 percent of all marine species and approximately 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrates. Scientists previously thought that after that global extinction event, it took many millions of years for animals to diversify and fill the planet's empty niches. But Antarctanax shows that archosaurs began diversifying within just a couple of million years after the Permian extinction, according to the study.

"If you look in the earliest rocks of the Triassic, archosaurs and other groups are radiating explosively," Peecook told Live Science. While Antarctanax's iguana-like body may not seem especially dramatic, some Triassic reptiles evolved to soar through the skies as pterosaurs, while others returned to the seas and eventually evolved into enormous ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs — and their ancestors were likely emerging at the same time as Antarctanax, he explained.

"The existence of Antarctanax in the early Triassic implies that all these other crazy lineages must have existed at this point already, even if we don't have a good fossil record of them from this time," Peecook said.

The findings were published online today (Jan. 31) in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- In Photos: Fossil Forest Unearthed in the Arctic

- Extreme Living: Scientists at the End of the Earth

- Image Gallery: Life at the South Pole

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus