What Is Cellulitis?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Cellulitis, not to be confused with cellulite, is a bacterial infection that typically occurs in the deep layers of the skin.

Symptoms

The skin around a cellulitis infection usually appears red and swollen and can be tender and warm to the touch. It may also look like it has been stretched tight and may even appear glossy, according to Healthline. On top of that, there could be an abscess filled with pus that forms near the center of the infection.

Cellulitis can also cause fever, chills, sweat, fatigue, lethargy, blistering, dizziness or muscle aches. These symptoms could mean that the cellulitis infection is spreading or becoming more serious.

Anyone with symptoms that may be related to cellulitis should immediately consult their doctor, as the infection can rapidly spread throughout the body, according to the Mayo Clinic. Untreated cellulitis can damage lymph nodes, infect the bloodstream, and can even become life-threatening.

Causes and diagnosis

Cellulitis is common infection that can affect anyone. According to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), there are an estimated 14.5 million cases of cellulitis diagnosed in the U.S. each year.

Adults typically experience cellulitis in the lower legs, although it can occur anywhere there's a break in the skin, according to Julie Maher, a clinical assistant professor of nursing at Carthage College in Wisconsin.

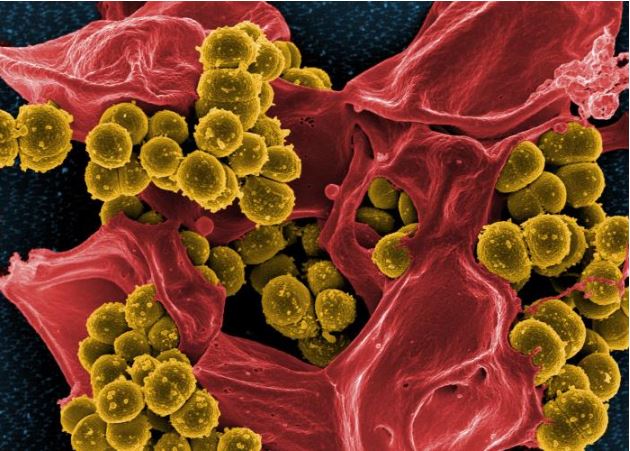

Several types of bacteria may cause cellulitis, the most common being the Streptococcus (strep), Staphylococcus (staph) and the difficult-to-treat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria, Maher told Live Science. These bacteria are among many that live on our skin and never present a problem in most healthy individuals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But if the bacteria enter the body through an opening in the skin, like a scratch or an open sore, then there's the possibility of infection.

People with other infections such as athlete's foot, a skin condition such as eczema (atomic dermatitis), or people who have had cellulitis in the past are more prone to cellulitis infections, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Cellulitis is also more common in people who tend to get skin injuries more often — rambunctious children, athletes, military personnel, residents of a long-term care facility and those who use intravenous drugs, according to the Mayo Clinic. Being obese might also increase the risk of developing cellulitis due to a decrease in blood circulation, Maher said.

Usually, doctors can quickly diagnose cellulitis on sight but will perform tests to determine the extent of the infection, according to Healthline. The doctor will assess things like the amount of swelling, the extent of the redness over the affected area and if any glands or lymph nodes are swollen. They might also take blood or skin samples to identify the bacteria causing the infection, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Treatment options

Cellulitis is often treated with oral antibiotics, according to the AAD, with rounds typically lasting seven to 14 days. More serious cases may require a hospital stay and intravenous antibiotics.

It's important to keep the infected area clean and covered, and to keep it elevated to help decrease swelling — a good reason to stay on the couch and away from other bacteria.

Most cases of cellulitis clear up quickly with these treatments but people with weakened or compromised immune systems might not be able to fight off the infection.

Left untreated, cellulitis can quickly spread throughout the body. According to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, untreated cellulitis can lead to complications including extensive tissue damage and tissue death (gangrene), as well as infecting the bones, lymph system, heart and nervous system.

Sepsis, or a blood infection, is a more serious complication that might arise from cellulitis, Maher said. Once the infection reaches the bloodstream, it can travel throughout the body, wreaking havoc from within. Sepsis is a life-threatening medical emergency, according to the Sepsis Alliance, and even with quickly administered treatment, it can lead to permanent health problems or death.

Preventative measures

Good hand hygiene is one of the best ways to reduce the chances of getting cellulitis, Maher said. All you need is soap, warm water and friction to decrease the number of bacteria living on the skin. In general, good skin hygiene will help keep skin moisturized and therefore limit cracks or openings in the skin that might result from dryness. Making sure your body is properly hydrated can also lower the chances of developing cellulitis.

But when you do get a cut, wash the wound as soon as possible with soap and warm water, before applying a protective ointment (such as a petroleum-based jelly like Vaseline or Aquaphor, or a topical antibiotic like Polysporin or Neosporin), the Mayo Clinic suggested. Bandages provide an additional layer of protection from bacteria and should be changed daily.

Check with your doctor about keeping open wounds such as blisters or more severe cuts clean and protected.

If there is a secondary chronic health condition, such as diabetes, then it's essential to keep up with treatments to help keep cellulitis from occurring or recurring and preventing further complications from the chronic condition, Maher said.

Additional resources:

- More information on group A steptococcal infections from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- Information about cellulitis from MedlinePlus.

- Education on skin infections from UpToDate.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Rachel Ross is a science writer and editor focusing on astronomy, Earth science, physical science and math. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from the University of California Davis and a Master's degree in astronomy from James Cook University. She also has a certificate in science writing from Stanford University. Prior to becoming a science writer, Rachel worked at the Las Cumbres Observatory in California, where she specialized in education and outreach, supplemented with science research and telescope operations. While studying for her undergraduate degree, Rachel also taught an introduction to astronomy lab and worked with a research astronomer.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus