Bird-Like Dinosaurs May Have Snuggled Together as They Slept

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

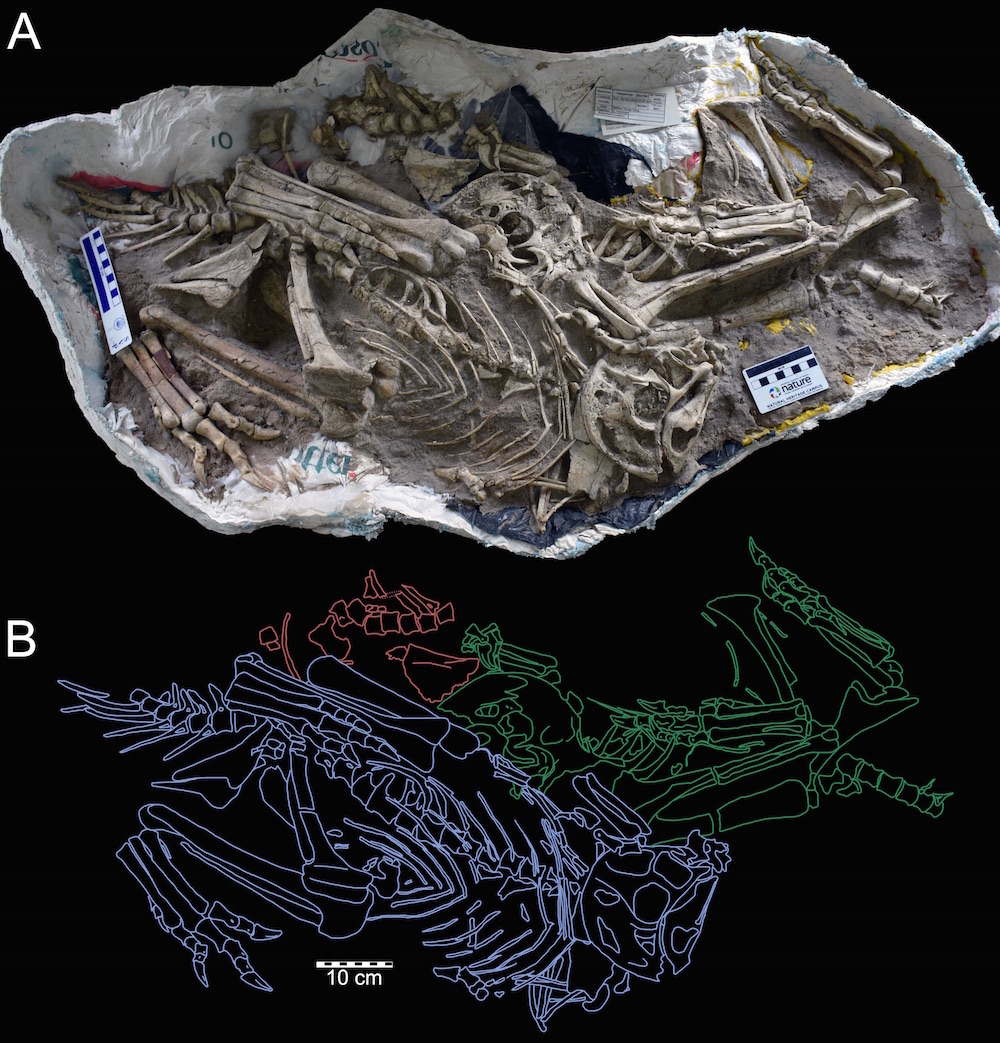

CALGARY, Alberta — Eleven years ago, Mongolian customs agents prevented poachers from smuggling a stone block out of the country that was filled with fossilized dinosaur bones. The rescue of this block has proved invaluable to scientists: It provides the first direct evidence that some dinosaur species roosted together — that is, snuggled with one another in a cuddly group when they fell asleep at night, new research finds.

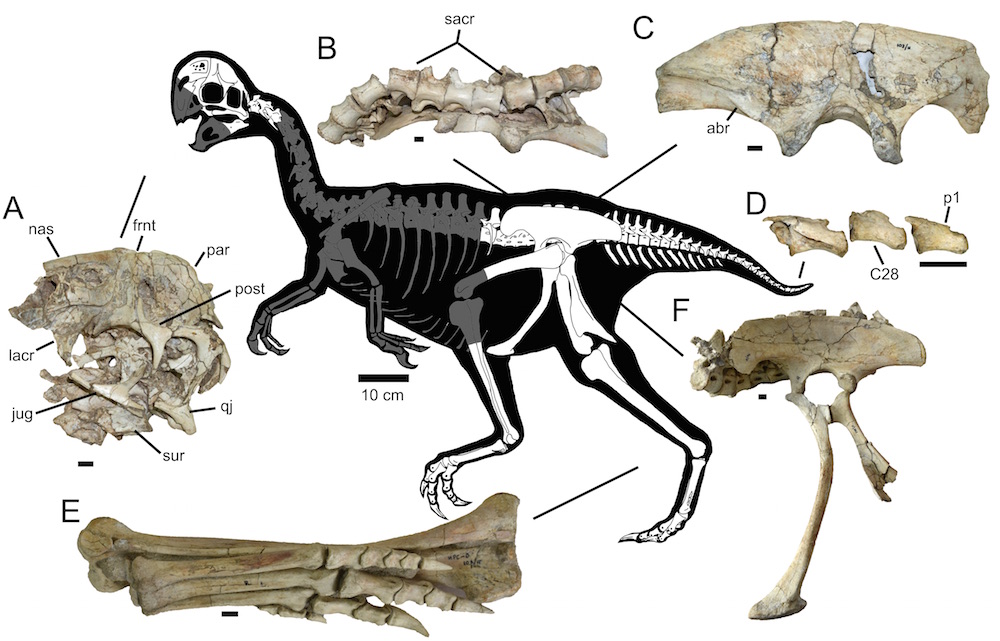

The fossilized bones, which belong to a newfound species that has yet to be named, have been identified as belonging to a group of bird-like, bipedal dinosaurs known as oviraptorids. Oviraptorids weren't large by dinosaur standards: most stood about 3 feet (1 meter) tall at their hips, and measured about 6.5 feet (2 m) long from beak to tail.

"This species has a rounded crest that is similar to a cassowary’s casque [head structure], so it would have been unusual-looking," said study lead researcher Gregory Funston, a doctoral student of biological sciences at the University of Alberta, in Canada. The dinosaur also had a toothless beak, feathers on its wing-like arms and a short tail with a fan of feathers at the end, he said. [Photos: Fossilized Dino Embryo Is New Oviraptorosaur Species]

The discovery of this unique species is providing more evidence of communal roosting. The specimens also include individuals of different ages, providing clues about how the dinosaur changed as it grew up. For instance, it's already clear that as the oviraptoridaged, the dinosaurs' head crest grew larger and its tail got relatively shorter, Funston told Live Science.

Moreover, it's possible the roosting oviraptorids were siblings, but more work is needed to say so for sure, Funston said.

Stopping smugglers

It's unknown when the poachers excavated the fossils, but customs agents caught the thieves in 2006, when they attempted to smuggle the bones out of Mongolia. The agents gave the bones to the Institute of Paleontology and Geology of Mongolian Academy of Sciences, where the fossils awaited study.

It's difficult to date a dinosaur without knowing the age of the rock layer in which it was found. Luckily, researchers from Japan legally unearthed an adult specimen of the same species in 1998 from Guriliin Tsav, in southwestern Mongolia, which dates to about 68 million years ago, Funston said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This individual lets us know what [rock] formation the species is from, and some geochemical work is ongoing by another team to determine where the poached specimens came from," Funston said.

Despite this extra work, Funston and his colleagues said they were delighted to study these mysterious oviraptorids.

"[The] poachers excavated a fantastic block of skeletons, which includes parts of three individuals, two of which are very complete," Funston said. "They are preserved in a sleeping posture, which suggests they were asleep when they died and were buried."

The dinosaurs' remains were so close together "that they would have been cuddling in life," he said. "This is a behavior known as communal roosting, where multiple animals of a single type sleep together overnight."

Bird-like behavior

Oviraptorids are theropods, the dinosaur lineage that led to the evolution of birds. It may come as no surprise that birds roost, but what's less well-known is that roosting is a complex social behavior, Funston said. [Photos: Birds Evolved from Dinosaurs, Museum Exhibit Shows]

"In birds, these behaviors are associated with social hierarchies and information sharing between individuals in a group," he said. It's unclear whether these behaviors were inherited from the common ancestor of birds and oviraptorids, or whether they developed convergently — meaning they separately evolved to have them because they face similar pressures in the environment.

So far, communal roosting appears to be convergent, Funston said.

"This would mean that birds and oviraptorosaurs had similar evolutionary pressures and behaviors," he said. "Essentially, these specimens may help us understand how communal roosting started in birds, by comparing the ways that birds and oviraptorosaurs are similar."

All in the family?

Modern animals, such as birds and bats, typically roost with siblings. There are several clues that the oviraptorid specimens from the "wonder block" are siblings: For instance, oviraptorids are known to lay eggs in clutches of two, meaning their young would be the same age, and the young individuals in the block are about the same size. But more work is needed to verify this idea, Funston said.

Researchers could study the dinosaurs' bones to determine whether they were the same age when they died, "but even then, we wouldn’t know if they were siblings," he said.

Scientists could also test whether the bones had the same chemical signatures at the same time in their development. "If we could show that they were born in the same season, drank the same water and ate the same food from the same place, we might be able to make a more convincing argument that they were siblings," Funston noted.

Given all these uncertainties, Funston and other researchers will be studying this newfound species for years to come. But even more importantly, these fossils raise awareness about the menace of poaching, he said.

"We’ve lost so much information about these animals because of poaching — where they were from, what kind of rock they were in, whether there were more of them — all in addition to the damage to the fossils themselves," Funston said. "This specimen could possibly be the poster child for its negative effects."

The research, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented today (Aug. 25) here at the 2017 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus