How Do Scientists Search for Extraterrestrial Life?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Human civilizations dating back thousands of years left behind structures and records documenting their studies of the stars as they sought to chart the seasons, help travelers find their way and interpret the world around them. Stargazers among the ancient Greeks, Maya, Egyptians, Middle Easterners and Asians likely also pondered if there were other planets like ours among those distant points of light — and if so, what might live there.

Over the last century, science-fiction storytellers have used books, movies, comics and television to speculate at great length about contact with creatures from other worlds — to our benefit and our detriment. These creatures have been imagined as sometimes benevolent and sometimes bloodthirsty, and they have come in a wide range of shapes and sizes — from inquisitive "little green men" to human-parasitizing, chest-bursting Xenomorphs in the "Alien" movie franchise.

Present-day astronomers have likewise been probing this question, using sophisticated equipment to listen farther and peer deeper into the universe than ever before, to find evidence of our cosmic neighbors. From detecting unexplained radio signals to investigating the atmospheres and liquid water on distant worlds — how are scientists searching for signs of extraterrestrial life? [Greetings, Earthlings! 8 Ways Aliens Could Contact Us]

For an alien-seeking scientist, "life" means any living form — including microbes, astronomer Mercedes López-Morales, at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, told Live Science.

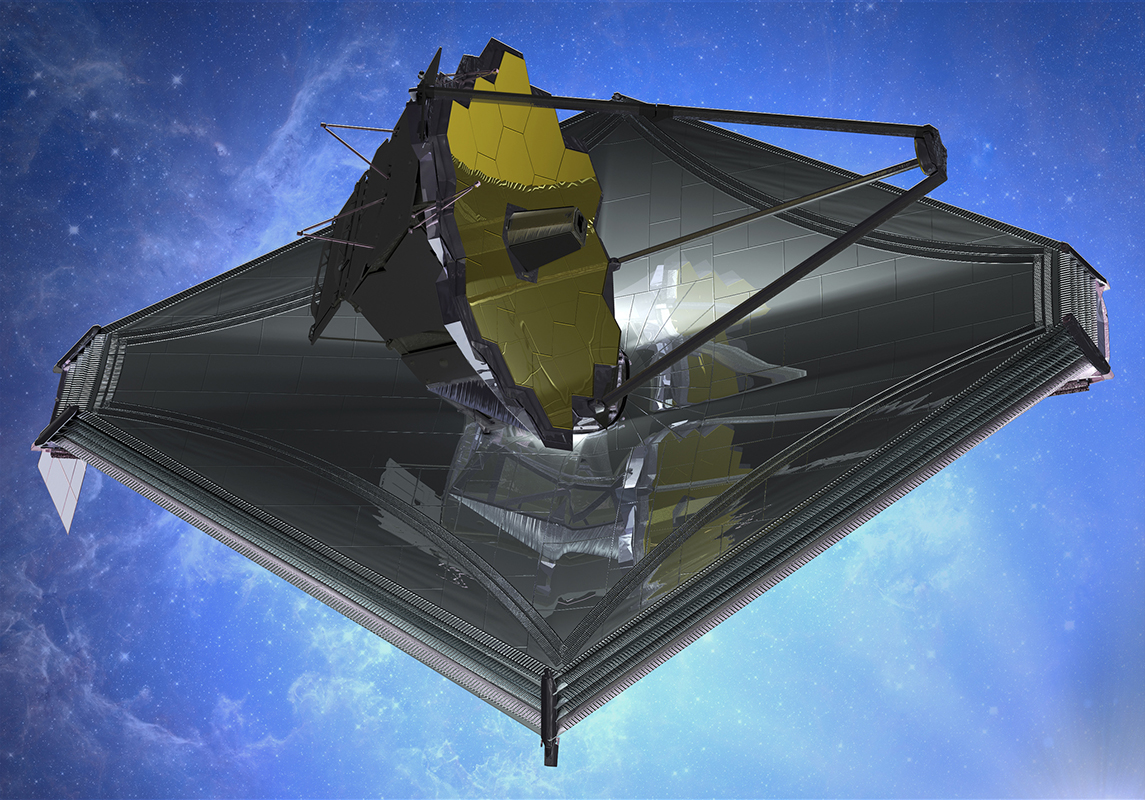

But even the smallest microbe living on a distant exoplanet — a planet orbiting a star other than our sun — could still broadcast a chemical signal that would be visible to sensitive telescopes, in the form of atmospheric gases that probably wouldn't be there in the absence of life, López-Morales explained.

"Life affects the atmosphere of a planet," she said. "You have gases that are only there because they are constantly being replenished by something — otherwise, they would react with other gases and disappear. For that gas or that molecule to be in the atmosphere of a planet, it must have some mechanism that is continuously producing it," López-Morales said.

One of the atmospheric gases astronomers are searching for in exoplanets is oxygen, which is plentiful in Earth's atmosphere because it is continuously being replaced by plants through photosynthesis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, the presence of unusual atmospheric gases doesn't necessarily mean that something living is generating them, López-Morales added.

"Sulfur molecules, for example, could come from active volcanoes," she explained. "For oxygen, there are at least two or three ways to produce it that involve irradiation in the ultraviolet light coming from stars. But we know that oxygen appeared on Earth because life appeared on Earth," she said.

Of course, even if these chemical signatures can be detected, there's no way to tell what forms of life are producing the signal, Sara Seager, an astrophysicist and planetary scientist at MIT, told Live Science in an email.

And what type of exoplanet is a good candidate for life? Our familiarity with our own world nudges efforts toward those that resemble Earth — "a rocky planet with a thin atmosphere with surface water," Seager said.

"Right now, we can tell — for some planets — if they are rocky, based on planet size and planet mass, which gives average density. But we can't yet tell if a planet has liquid water," she said. [A Field Guide to Alien Planets]

Location, location, location

What else makes an exoplanet a promising candidate? "Anything close by," López-Morales told Live Science. For an astronomer, that means less than 30 light-years away, which would enable humans to actually visit the world where life was detected, she said. (One light-year is about 5.9 trillion miles, or 9.5 trillion kilometers.)

"Eventually, I hope humans will have the technology to get that far, within a reasonable number of years. So for us, the holy grail is to find something within 30 light-years of Earth," she said.

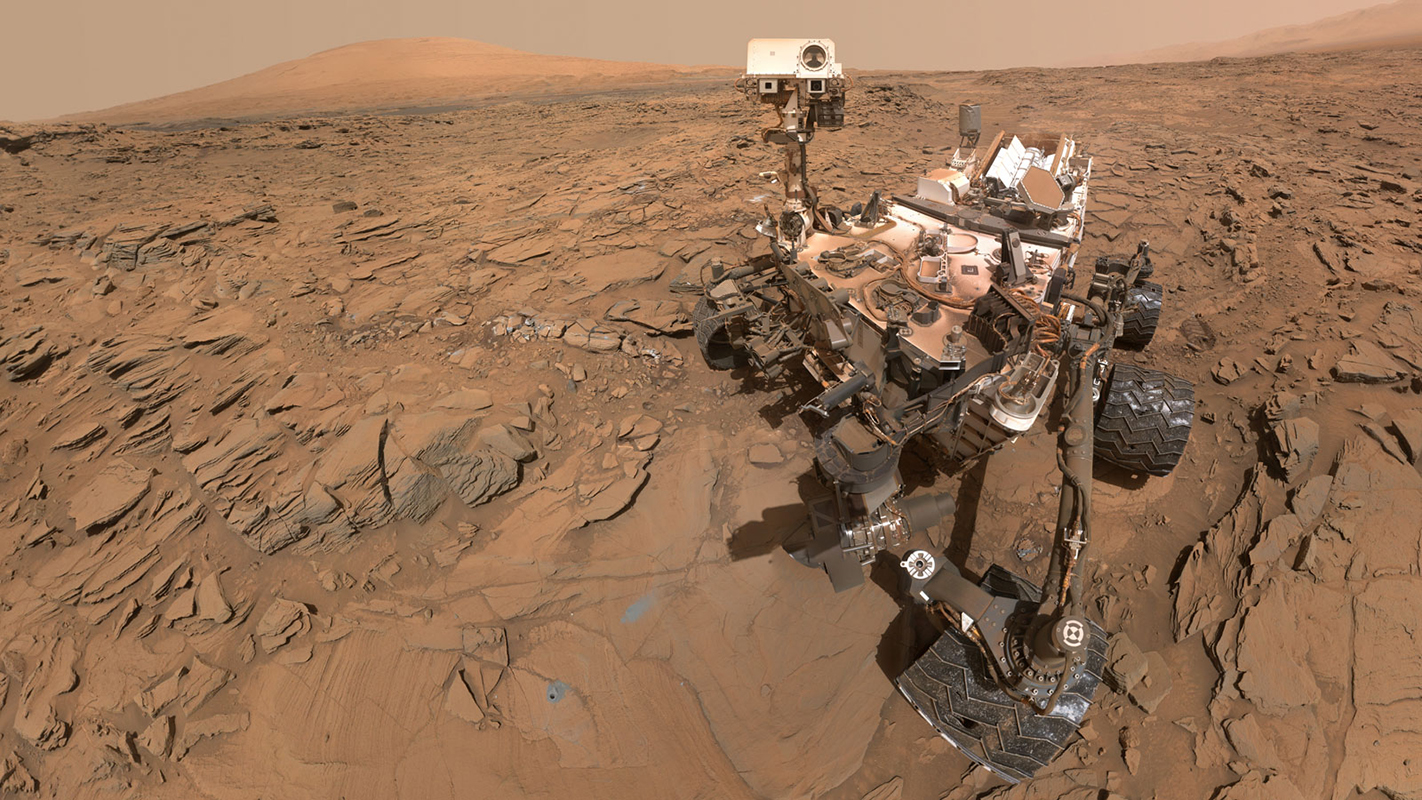

Scientists are also investigating worlds within our own solar system — such as the Saturn moons Titan and Enceladus — which are close enough to be visited by probes that can collect samples and capture images. Several NASA missions are also looking closely at Mars, which once had abundant liquid water on its surface, and where brackish water still flows today, researchers announced in 2015.

"Humans are creatures that want to know — where we came from, where we're going, how we appeared on Earth," López-Morales said. "Our research might start providing answers to that." [FAQ: Significance of Liquid Water on Mars]

Radio signals

But scientists aren't just looking for signs of extraterrestrial life — they're also listening for them.

For more than two decades, SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute, has conducted research to understand the origins of life in the universe, and to detect and analyze evidence of life emanating from places other than Earth. This effort includes investigations of microbial life within our solar system, such as on the surface of Mars or under the icy crust of Jupiter's moon Europa. SETI scientists are also monitoring the universe for signals in light or radio wavelengths that originate far away and could be signs of technologically advanced alien life, SETI explains on its website.

At SETI, astronomers use the Allen Telescope Array (ATA) of 42 radio antennas to "listen" for signals over a range of radio frequencies, tuned to "hear" the regions around 20,000 red dwarf stars (a broad term describing stars smaller than our sun and in a certain spectral range) that are closest to Earth, Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer at the SETI Institute, told Live Science.

Investigating red dwarf stars for life-supporting worlds is a relatively recent development at SETI. In the past, stars that were more like our own sun — a yellow dwarf — were thought to be the most likely candidates to host planets harboring life. But over the last few decades, astronomers have determined that many red dwarf stars host planets that could be at the right distance from the star to be habitable, according to Shostak.

"That's something we didn't know when we started," he said.

And SETI radio-signal monitoring is accelerating, as telescopes become more sensitive and technological developments increase the number of radio channels and locations in the sky that can be studied at once, Shostak explained.

"Until now, the total number of star systems that have been looked at carefully over a wide range of the radio dial is measured in the thousands. In the next 20 years, with new technology, you could increase that number to maybe a million," he said. [4 Places Where Alien Life May Lurk in the Solar System]

An alien megastructure?

Shostak also reviews images of alleged alien spacecraft sent to him by hopeful photographers, he told Live Science. A photographer himself, Shostak said that he invariably identifies all the purported "UFO" sightings as tricks of the light or internal reflections in the camera lens — much to the dismay of the observers.

"That never makes them happy," he said.

But even among astronomers, unusual observations can sometimes turn the conversation toward the likelihood of alien technology.

In 2015, when scientists discovered the star KIC 8462852 — also known as Tabby's Star, located more than 1,400 light-years from Earth — they were puzzled by repeated and significant dips in its brightness that took place over several years. During the dips, the star dimmed by as much as 22 percent, far more than could be caused by an orbiting planet passing in front of the star, Shostak said.

In short, the star was "really weird," Tabetha Boyajian, lead author of a study about the star and a researcher at Yale University, told the Atlantic in October of that year.

One possible explanation suggested by some experts was an "alien megastructure," an enormous array orbiting KIC 8462852, built by a hypothetical alien civilization advanced enough to possess technology capable of drawing power from a star. Such a construct could — in theory — periodically block visible light and make the star appear dramatically dimmer when seen from Earth, Space.com reported in 2015.

However, there is no data to actively support this hypothesis. In fact, on all fronts, evidence of any extraterrestrial presence — within our own solar system or beyond its boundaries — remains elusive. But scientists seeking life on other worlds are undaunted by the ongoing challenge, Shostak told Live Science.

"The search should continue, simply because it's a very interesting question," he said.

"Is Earth special? Is it the only place around with intelligent life? That would be remarkable — but it's just as remarkable to find you're not the only kid on the block. That's something that would change our view of ourselves forever," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus