How Did Pluto Get Its 'Whale'?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

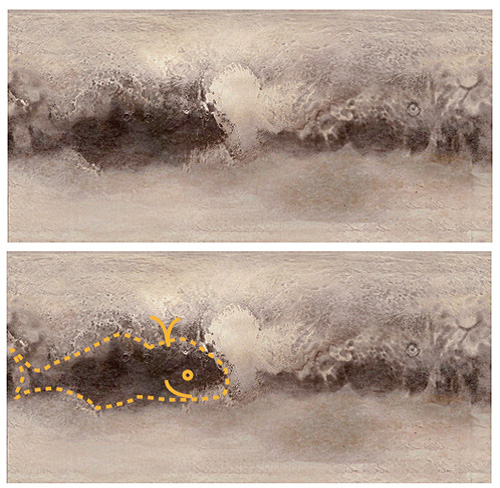

In 2015, scientists learned that there’s a giant red "whale" on Pluto. This dark-colored region could be the mark of a giant impact — the same one that produced Pluto’s huge moon Charon, according to a group of researchers in Japan.

The surface of Pluto — the biggest object inside the Kuiper Belt, the ring of ice bodies beyond Neptune's orbit — remained mysterious for decades. Astronomers knew the dwarf planet as little more than a blurry orb until NASA's New Horizons probe revealed its surprisingly complex features in high definition during a flyby in July 2015. [Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures]

Thanks to that mission, we now know that Pluto has towering ice mountains, blue skies, a 620-mile-wide (1,000 kilometers) heart-shaped nitrogen glacier, jagged faults and, potentially, an underground ocean.

One of the most prominent features on Pluto is the informally named Cthulhu Regio, also called "the whale," which stretches across 1,900 miles (3,000 km). Cthulhu Regio is pockmarked with craters, which suggests it is billions of years old — much older than the craterless, young "heart" it borders. Scientists have said the dark region's reddish coloring might come from tholins, which are complex hydrocarbons.

To further investigate how the whale got its coloring, Yasuhito Sekine, an associate professor at the University of Tokyo, conducted heating experiments on organic molecules, like formaldehyde, that would have been present on the newly forming Pluto soon after the formation of the solar system. Sekine found that he could produce the same dark, reddish color after heating solutions above 122 degrees Fahrenheit (50 degrees Celsius) for several months.

Meanwhile, Hidenori Genda, an associate professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, conducted computer simulations of a giant impact on Pluto. Genda found that the same impact that would have created Pluto's moon Charon, which is about half the size of Pluto, could have created a huge pool of hot water near Pluto's equator. And as this giant hot-water pool cooled, reddish complex organic materials would have formed, according to the findings, which were presented at the annual meeting of the European Geosciences Union in Vienna last month and were also published in the journal Nature Astronomy earlier this year. "For the terrestrial planets in our solar system, giant impacts are common," Genda told Space.com. "Our results suggest that giant impacts are common in [the] outer system beyond the Neptune orbit."

The color of an impact

The color changes across Pluto "make an interesting pattern, and we don't have good ideas to explain all of these features, so we are all still in the initial stages [of] exploring different hypotheses to explain these variations," said Kelsi Singer, a co-investigator on the New Horizons extended mission at the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Singer, who wasn't involved in the new study, isn't entirely convinced by the newly described impact scenario. She told Space.com in an email that it is unlikely that the "whale" has remained mostly the same for the past 4 billion years or so, because the region has a lot of variation within it.

"There are some heavily cratered areas, and some smoother, almost crater-free areas that have younger ages," Singer said. "You could perhaps argue that if the dark layer was very thick (more than a few km) you could keep it around for 4 billion years or longer and still have other craters form in it, tectonics fracturing it, and keep it dark."

But Singer said that in most areas of the whale, the dark material does not seem to be thick; thinner patches of the dark material are sitting on top of a brighter surface. Singer thinks a simpler explanation for the whale's coloring could be that the dark material formed from methane being processed by radiation on Pluto's surface or in the atmosphere.

To fully confirm the chemical makeup and impact history of Pluto, scientists might need to send additional space telescopes to observe the dwarf planet, or perhaps, one day, a probe to sample the icy surface.

"If we can get some information on chemical compositions of complex organic matters in the whale region, it will help us to confirm or deny the impact origin of this region," Genda said. "UV spectra will give us that information, but unfortunately, New Horizons did not have a UV spectra instrument. Ultimately, sample return from the whale region can reveal the origin of this region."

Follow Megan Gannon @meganigannon, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus