Why are bananas berries but strawberries aren't?

A strawberry isn't a berry. But scientifically speaking a banana is a berry. So what's the deal? Why are berries so hard to define?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Despite its name, the strawberry isn't a true berry. Neither is the raspberry or the blackberry. But the banana is a berry, scientifically speaking, as are eggplants, grapes and oranges.

So what's the deal? Why are berries so very hard to define?

The discrepancy in berry nomenclature arose because people called certain fruits "berries" thousands of years before scientists came up with a precise definition for the word, said Judy Jernstedt, a professor of plant sciences at the University of California, Davis. Usually, people think of berries as small, squishy fruit that can be picked off plants, but the scientific classification is far more complex, Jernstedt said.

Article continues belowRelated: What's the difference between a fruit and a vegetable?

Judy Jernstedt is a professor of plant sciences at the University of California, Davis. Jernstedt specializes in the structure and development of crop plants, plant anatomy and evolutionary morphology, among others. Jernstedt received a doctorate in Botany from the University of California, Davis in 1979, and a master's in Plant Physiology from the same university in 1974.

What is a berry?

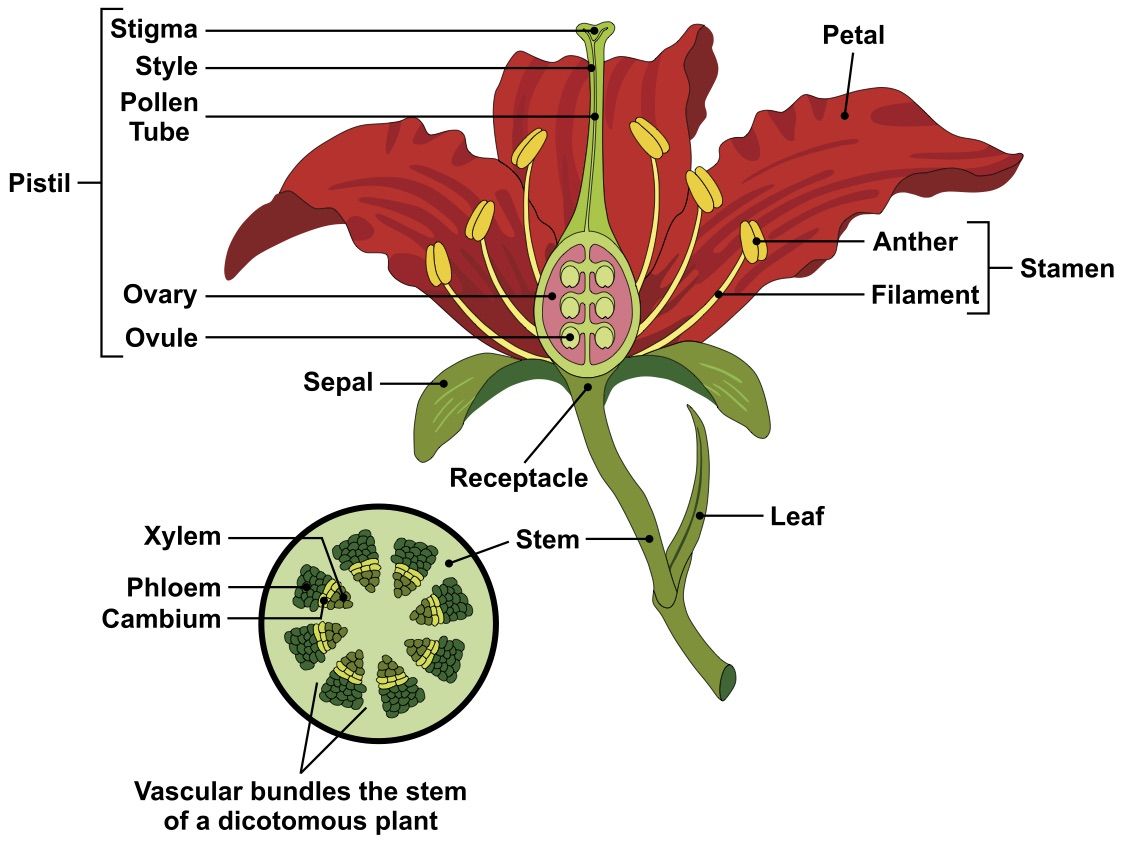

Botanically speaking, a berry has three distinct fleshy layers: the exocarp (outer skin), mesocarp (fleshy middle) and endocarp (innermost part, which holds the seeds).

Botanically speaking, a berry has three distinct fleshy layers: the exocarp (outer skin), mesocarp (fleshy middle) and endocarp (innermost part, which holds the seeds). For instance, a grape's outer skin is the exocarp, its fleshy middle is the mesocarp and the jelly-like insides holding the seeds constitute the endocarp, Jernstedt told Live Science.

The same layered structure appears in other berries, including the banana and watermelon, although their exocarps are a bit tougher, taking the form of a peel and a rind, respectively. (The suffix "carp" comes from the word "carpel," which refers to the pistil, the female organ of the flower, Jernstedt said.)

To be a berry, fruits must develop from one flower that has one ovary.

In addition, to be a berry, a fruit must have two or more seeds. Thus, a cherry, which has just one seed, doesn't make the berry cut, Jernstedt said. Rather, cherries, like other fleshy fruit with thin skin and a central stone that contains a seed, are called drupes, she said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Moreover, to be a berry, fruits must develop from one flower that has one ovary, Jernstedt said. Some plants, such as the blueberry, have flowers with just one ovary. Hence, the blueberry is a true berry, she said. Tomatoes, peppers, cranberries, eggplants and kiwis come from a flower with one ovary, and so are also berries, she said.

Other plants, such as the strawberry and the raspberry, have flowers with more than one ovary.

"Raspberries have those little subunits," Jernstedt said. "Each one of those little subunits comes from an individual ovary. And those subunits are actually [called] drupes."

Each drupe contains a seed; that's why wild raspberries and blackberries are so crunchy, according to Jernstedt. Because these types of fruit consist of so many drupes, they're called aggregate fruit, Jernstedt said. A strawberry is also an aggregate fruit, but instead of having multiple drupes, it has multiple achenes, the little yellow ovals on the fruit's surface, which each contain a seed.

Oranges are a subtype of berry called hesperidium, said Courtney Weber, a berry breeder at Cornell University in New York. Like other berries, oranges have three fleshy layers, have two or more seeds, and develop from one flower with one ovary. But citrus fruits contain distinct segments, a property that differentiates these fruits from other berries and gives them the subtype status, Weber said. (The number of sections is related to the number of carpels, Jernstedt said.)

In all, berry categorization "is kind of chaotic," Jernstedt said. "And the scientists feel that way too. There are always attempts to impose some order on fruit classification. But this has been going on for a couple of centuries, so don't hold your breath that it's going to be solved soon."

In other words, it can be difficult to classify nature's many fruits, which evolve without a thought about how scientists will view them.

"Flowering plants have devised a number of ways to produce seed and to get that seed distributed," Weber told Live Science. "Having the fleshy fruit types that we eat is just nature's way of getting animals to eat this fruit and seed and distribute them."

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus