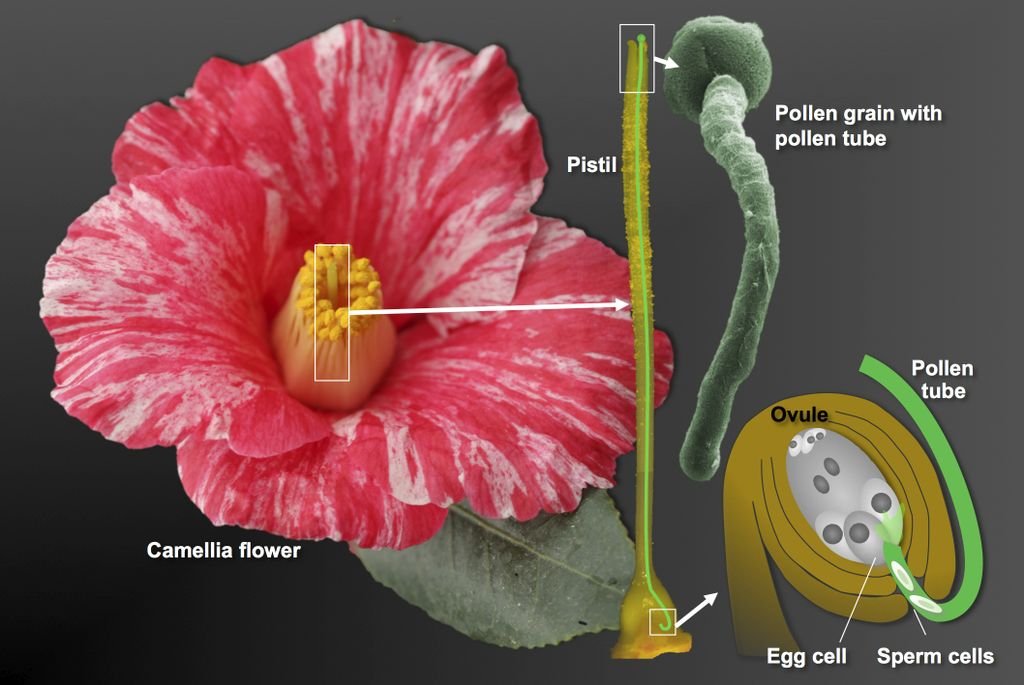

Gallery: Tantalizing Images of Plant Sex

Plant Sex

Plant reproduction and its human counterpart aren't all that different, a new study detailed in April 2013 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests. When a pollen grain, which stores plant sperm, lands on top of the stigma, a structure that sits atop the carpel where the female sex cells are stored, the pollen grows a long tube that pushes through the surrounding tissue. The pollen tube swells up like an inflating balloon, navigating a narrow channel to deliver sperm to the ovules, where it fertilizes an egg cell.

But when the tube encounters too much tightening force from the tissue, pollen tube bursts and releases sperm. Scientists captured the delicate act in these amazing microscope images.

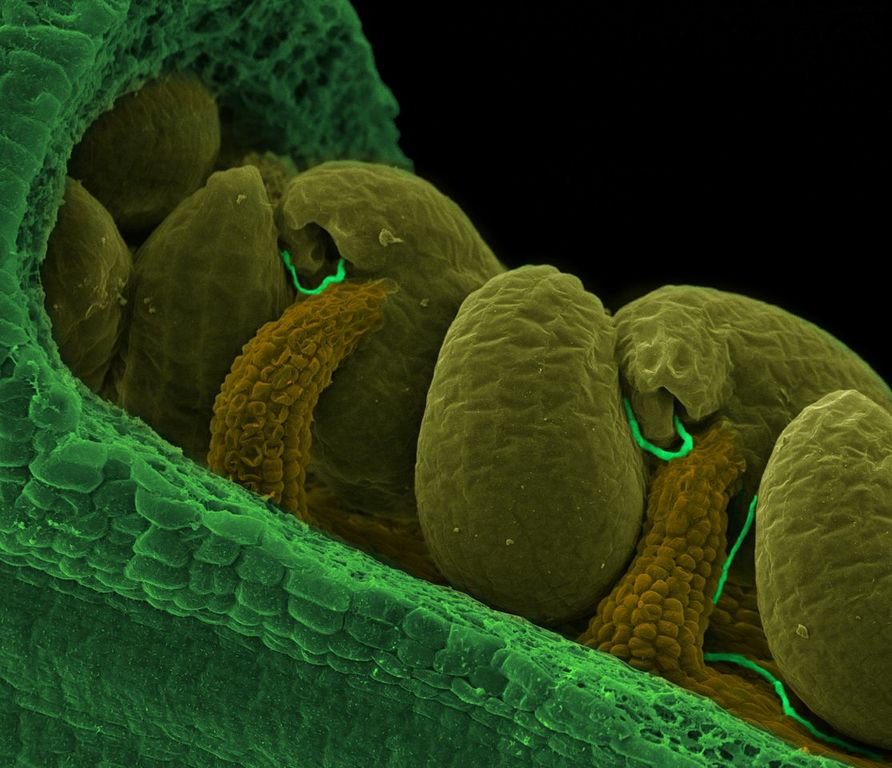

Flower Pistil

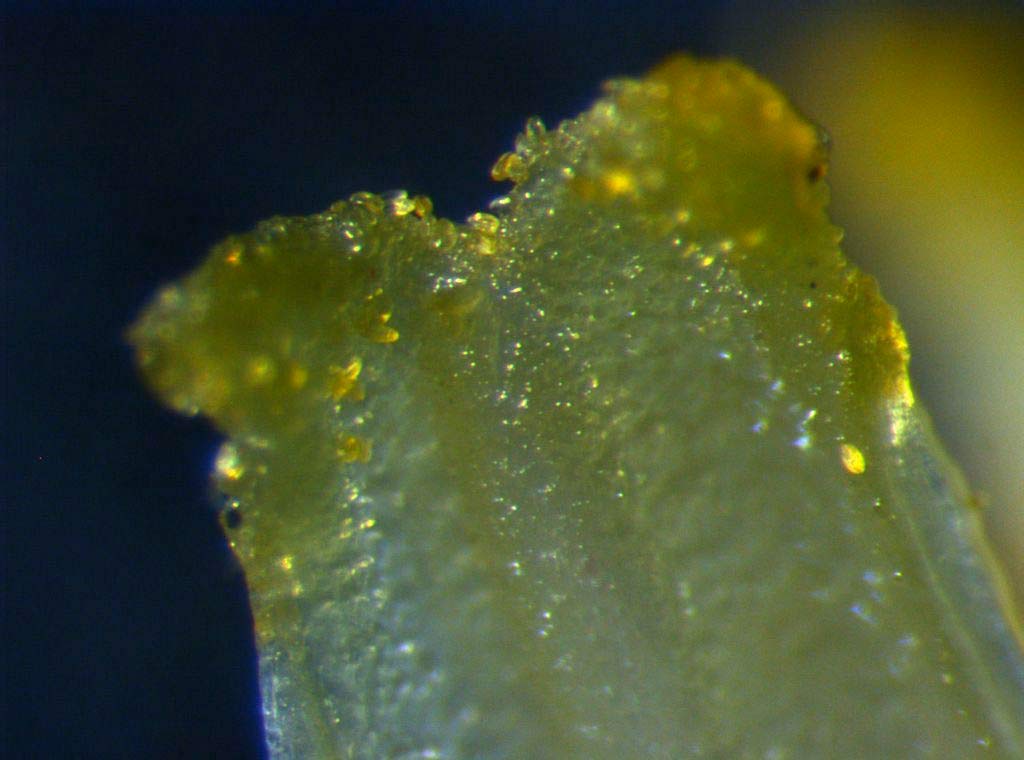

Inside of the pistil, or ovule-producing part of a flower, of an Arabidopsis flower revealing the ovules being fertilized by pollen tubes (thin green lines).

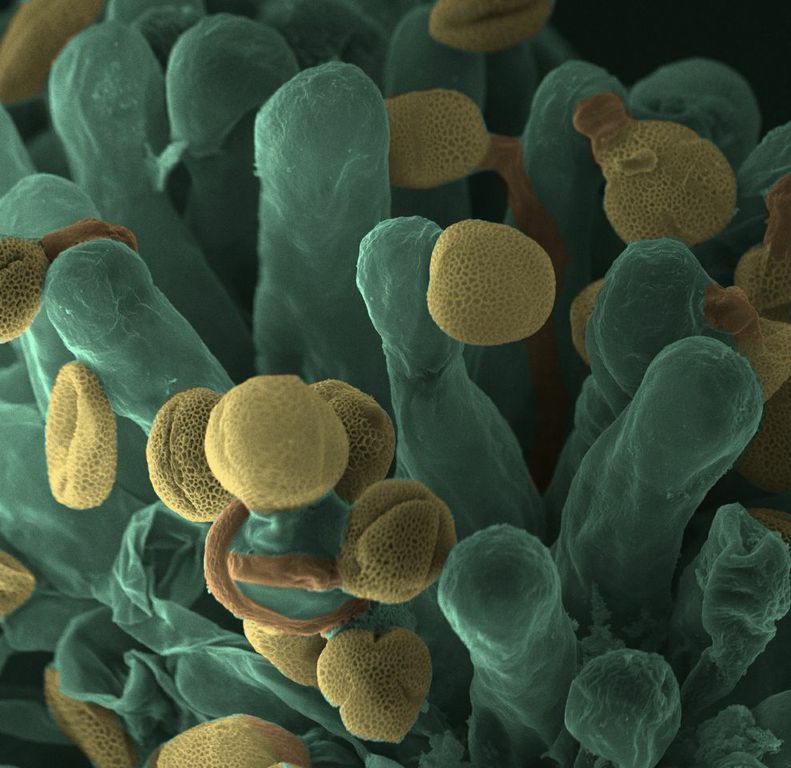

Flower Stigma

A scanning electron micrograph of germinated pollen grains attached to the stigma of an Arabidopsis flower pistil.

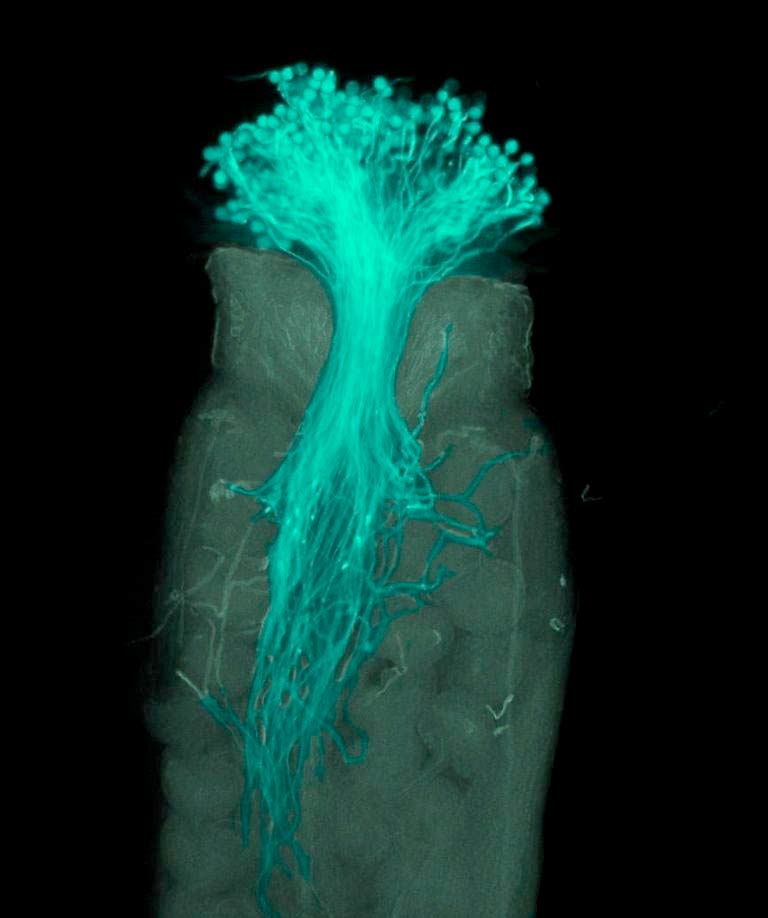

Growing Pollen Tube

Fluorescence micrograph of a pollinated Arabidopsis pistil, showing the pollen grains (teal-colored sphères) and the pollen tube (thin teal-colored lines) growing into the pistil toward the ovules.

Anthers Up-Close

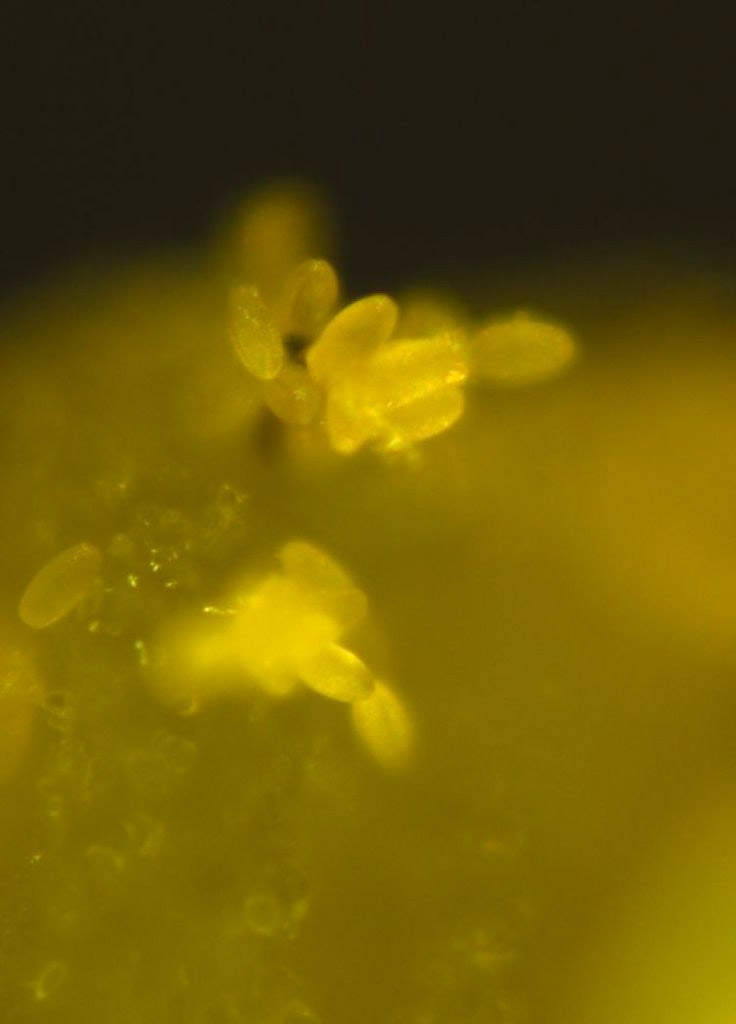

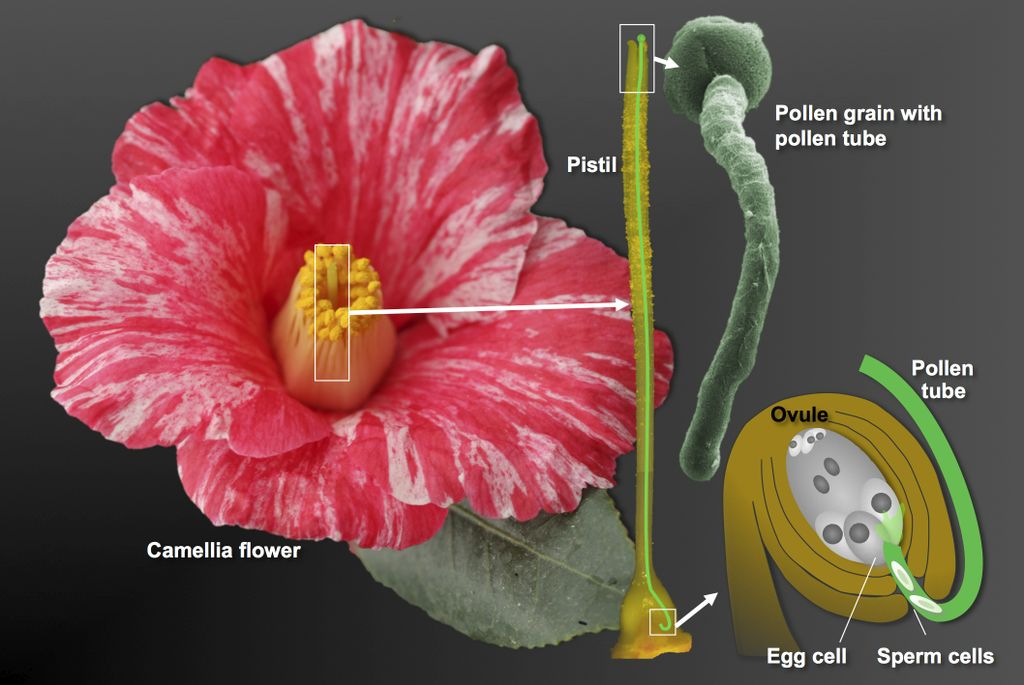

Close-up top view of the stigma and anthers, or the part of the stamen where pollen gets produced, of a Camellia flower.

Floral Beauty

Another close-up image of the Camellia flower and its anthers.

It's a sprout

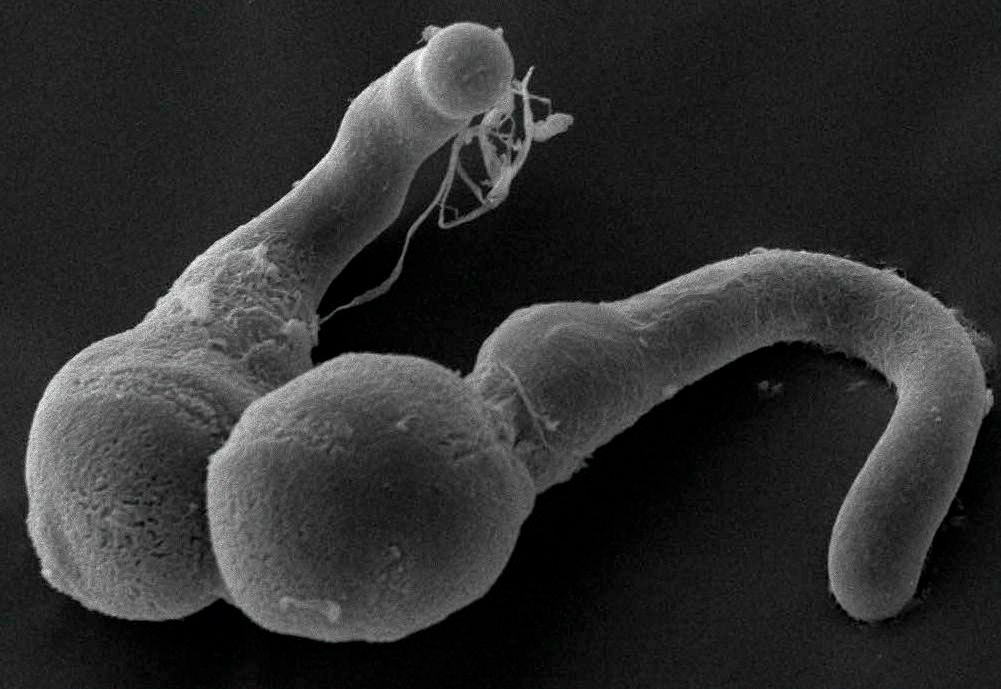

Scanning electron micrograph of two germinated pollen grains from the Camellia flower.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sticky Pollen

Here a loook at the pollen grains of the Camellia flower attached to a stigma.

Pretty Stigma

Close-up side view of the stigma and anthers of a Camellia flower.

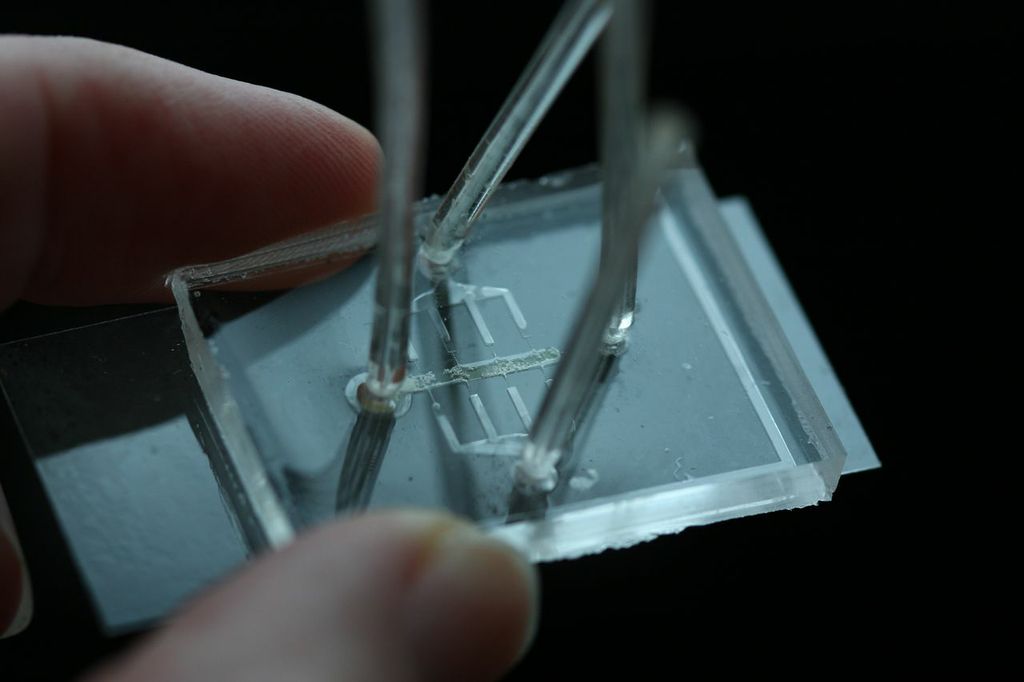

Sexy Chip

Anja Geitmann, a biologist at the University of Montreal in Canada, wondered how a plant's pollen tube generates the forces necessary to penetrate surrounding cells that resist its growth. To find out, the researchers developed a special chip (shown here) to measure the forces a pollen tube encounters as it grows.

Scoop on Sex

Here's how the researchers think plant sex goes down in the Camillia plant: The pollen grain attaches to the stigma situated on top of the pistil, which is about 1.2 inches (3 cm) long, and the tube grows all the way down to the ovary where it discharges the two sperm cells within an ovule. One sperm cell fertilizes the egg cell. The other sperm cell fertilizes the central cell of the same ovule to give rise to the endosperm, a tissue the nourishes the growing embryo.