Huge Claw, Bizarre Limbs Helped Ancient Reptile Dig

About 200 million years ago, a reptile resembling a chameleon wielded a digit on each of its front legs with a massive claw, and used that claw as a digging tool in a manner similar to that of modern anteaters.

However, the oversize claws weren't even the weirdest part of this animal's forelimbs, according to a new study describing fossils of the unusual appendages.

The front limbs of most tetrapods — four-limbed animals with backbones — share certain similarities in bone arrangement and shape. But this unusual reptile's forelimb structure diverged dramatically, suggesting that early tetrapod limbs may have been more diverse than previously suspected. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

The first fossil of this ancient, chameleon-like reptile — known as Drepanosaurus and measuring about 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) in length — was found in Italy in the 1970s and was described in 1980, according to study author Adam Pritchard, a postdoctoral fellow with the Department of Geology at Yale University.

But the fossil, though mostly preserved, was badly crushed, Pritchard told Live Science.

Scientists managed to isolate individual bones just enough to suggest the creature had odd front limbs. But to reconstruct the limbs to see what they actually looked like would take more, uncrushed, fossil material.

That material didn't emerge until decades later.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Armed and dangerous

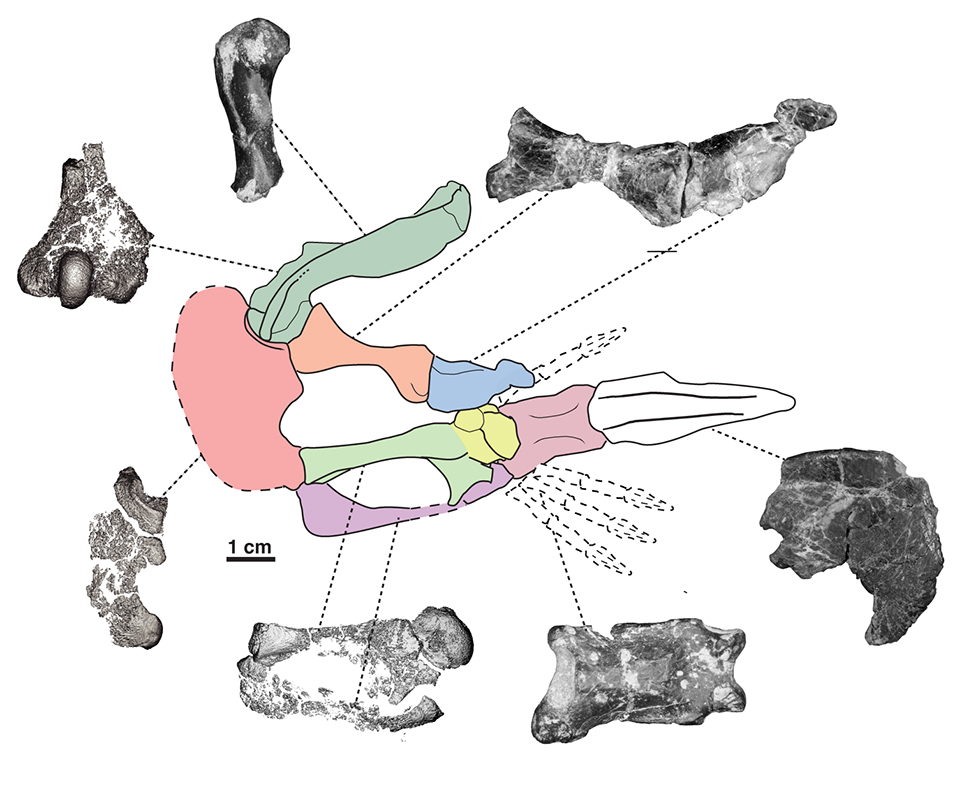

In 2010, Pritchard began investigating fossils excavated by the study's other co-authors, in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico. He and his colleagues identified three Drepanosaurus specimens that were preserved in 3D, providing a first glimpse of the forelimbs that had intrigued scientists 30 years earlier.

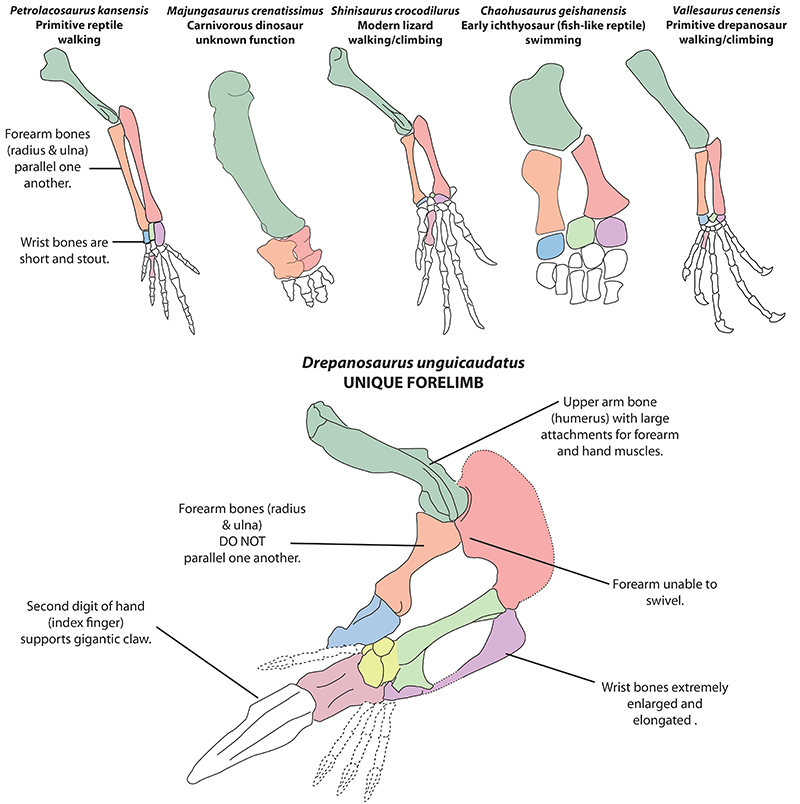

Pritchard explained that tetrapod forelimbs follow a basic plan: a single bone, the humerus, attaches to the shoulder. Attached to the humerus are two elongated parallel bones, the radius and ulna, which meet a series of shorter wrist bones at the base of the hand.

Drepanosaurus, however, had two differently shaped bones extending from the humerus that were not parallel. One was shaped like a crescent moon, Pritchard said. Attached to this crescent-moon bone were two long and slender wrist bones that were much longer than the other wrist bones.

"The idea we confirmed with the new fossils was that the crescent moon bone was, in fact, the ulna," Pritchard said. "Drepanosaurus maintains the traditional bones that make up the forelimb, but they're radically altered."

Can you dig it?

The fossils were so well-preserved that the study authors were able to see where the forelimb bones would have met one another, so they could determine the animal's range of motion. The scientists determined that Drepanosaurus was capable of powerfully moving its forelimb forward and pulling it back, but probably couldn't raise or lower the limb much.

Since the forelimbs were tipped with giant claws, this suggested that Drepanosaurus used its arms for digging, in a method employed by modern anteaters called "hook and pull," the researchers said.

"It involves hooking the claw powerfully into substrate and pulling the entire forelimb back, using the entire musculature of the arm to rip open whatever it's attacking at the time," Pritchard explained.

And the mechanics of Drepanosaurus' unusual forelimb are just the beginning of what scientists are poised to discover about this mysterious group of animals, Pritchard said.

"We have a lot more 3D-preserved fossils that are going to be able to answer questions about what the rest of the skeleton looked like — like the head and the claw at the end of the tail," he said.

The findings were published online today (Sept. 29) in the journal Current Biology.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.