10 'Barbaric' Medical Treatments That Are Still Used Today

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Medieval treatments?

In fashion, it seems that everything old becomes new again. But that is not always the case in medicine, a field that is continually striving to discover and use the most modern technologies and advanced techniques to improve people's health.

However, there are some age-old medical practices that are still in use today. These older medical approaches may seem medieval or sound like "barbaric" treatments in the 21st century, but research has shown that they are actually effective, and have a legitimate medical use.

Related: Animal Data Is Not Reliable for Human Health Research (Op-Ed)

Medical procedures and remedies need to be understood in their historical context because the rationale for their use long ago is often very different from the reasons for using them today, said Dr. Scott Podolsky, an internist at Massachusetts General Hospital and the director of the Center for the History of Medicine at Countway Library at Harvard Medical School in Boston. [10 Medical Conditions That Sound Fake but Are Actually Real]

Here are nine examples of "barbaric" medical treatments that have modern-day relevance, along with a look at why doctors may turn to these older approaches, and their potential risks.

Bee venom therapy

Bee venom therapy — which involves being willingly stung by a live honeybee, or injected with bee venom — dates back to the time of ancient Greece, when Hippocrates purportedly believed in the medicinal value of bee venom to ease arthritis and other joint problems, according to the American Apitherapy Society. (Apitherapy refers to all medical-related therapies that are based on bee products, including bee venom, honey or pollen.)

The reason it may help is because bee venom contains melittin, a chemical thought to have anti-inflammatory properties, according to a 2016 study published in the journal Molecules.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although bee sting therapy is promoted for relieving the pain and swelling of arthritis and for preventing relapses, fatigue and disability in people with multiple sclerosis, there is a lack of scientific evidence of its effectiveness for these two conditions, and it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this use.

Not only is there limited research of its benefits, but the treatment itself may be harmful to some people: A review study by researchers in South Korea published in 2015 in the journal PLOS ONE concluded that people frequently get adverse reactions to bee venom therapy.

Risks can range from minor skin reactions and pain at the sites of the stings to life-threatening anaphylaxis reactions in people who may be allergic to the venom, according to the study.

These days, bee venom therapy is more commonly used in Asia, Eastern Europe and South America than in the U.S., where it is considered an alternative medical therapy.

Maggot therapy for wound healing

Compared to other treatments described in this article, maggot therapy is fairly new, having been used for only about 100 years, said Dr. Ronald Sherman, an internal medicine physician and director of the BioTherapeutics, Education and Research Foundation in Irvine, California, a nonprofit organization that promotes the use of live animals to diagnose and treat illness. [Ear Maggots and Brain Amoebas: 5 Creepy Flesh-Eating Critters]

The treatment consists of applying live "baby flies," or the fly larvae, to a wound. Military surgeons first observed maggots to be beneficial when injured soldiers who remained on the battlefield were found to heal quicker if flies were allowed to lay eggs in their wounds. By 1928, a Johns Hopkins physician developed a way to cultivate medical-grade maggots and make them germ-free before their use in treatment.

In 2004, the FDA issued a clearance that allowed maggots to be marketed for medical use on wounds that are slow to heal, such as diabetic foot ulcers and bed sores. They also may be used for chronic leg ulcers, post-surgical wounds and acute burns.

Maggot therapy is done by applying the bugs to the surface of a wound and covering it with a dressing for about two days. The hungry critters secrete digestive enzymes that can dissolve the wound's dead and infected tissue, a process known as debridement, Sherman said.

Maggot therapy fell out of use in the 1950s with the widespread availability of antibiotics, but has re-emerged in the 21st century with the rise in antimicrobial resistance and hard-to-treat wounds, Sherman said.

"Maggots are very good at getting rid of rotting flesh," Sherman told Live Science. But one hurdle the treatment often needs to overcome is the yuck factor.

"Our culture equates maggots with death, dog doo and stinky garbage," Sherman said.

Medical leeches for venous congestion

Leeches are primitive worms (Hirudo medicinalis) that are equipped with suckers on their front and back ends that let them feed on blood, and teeth that can make a quick, clean cut, Sherman said.

These qualities make leaches useful for "bloodletting," a medical practice that removes blood from the body and dates back to ancient times.

In the 21st century, the FDA has cleared the use of medical leeches for a condition called venous congestion, in which blood pools in a particular area of the body and the veins can't pump it back to the heart, Sherman said. Venous congestion may occur following surgeries to reattach a limb, such as a finger or an ear, for example, or other major surgical reconstructions, such as a breast, he explained.

Leeches can extract a significant volume of blood from a surgical site in a short amount of time, about 45 minutes, which allows more oxygen to reach the site, Sherman said.

In addition, the saliva from leeches contain substances with anticoagulant properties, meaning they can prevent the blood from clotting, he added.

One major risk of leech therapy is anemia, or the loss of too much iron, Sherman said. It's also possible to get an infection at the site where the leeches bite the person's skin, he explained. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

Bloodletting for hemochromatosis (iron overload)

The most common reason for modern-day bloodletting, which is now called therapeutic phlebotomy, is hemochromatosis, a genetic disorder caused by an overload of iron in the body, Podolsky, of Massachusetts General, said.

When too much iron accumulates, it can be toxic to the liver, heart, pancreas and joints. To rid the body of extra iron by therapeutic phlebotomy, a doctor uses a needle to draw a pint or more of blood from the patient, once or twice a week for several months or longer, so that the person's levels of ferritin (a protein that stores iron) fall into a healthier range, Podolsky explained.

Therapeutic phlebotomy is an extremely effective treatment for hemochromatosis, Podolsky said. "It does the trick," he said.

This modern-day version of bloodletting is similar to the idea behind the use of bloodletting back in the 18th century, Podolsky said. There is a notion of excess — in this case, excess iron in the body, and removing blood lowers the excess iron levels and helps the patient, he said.

But the similarity of today's treatments with 18th century bloodletting ends there, Podolsky told Live Science. Back then, removing blood was done to restore balance in the body and supposedly help ease a wide range of illnesses, he said. [7 Weirdest Medical Conditions]

The most common side effects of removing blood to treat hemochromatosis include feeling tired and becoming anemic if too much blood is withdrawn as well as the possibility of infection, Podolsky said.

Electroconvulsive therapy for severe depression

Although not considered ancient because it was first developed in the late 1930s and introduced in the U.S. about one year later, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may have gained a modern-day reputation as a barbaric treatment when it was famously depicted in the movie "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" and administered unwillingly to Jack Nicholson's character.

Once known as electroshock therapy or simply called "shock treatment," ECT involves passing electrical currents through the brain, either by implanting electrodes in the brain or placing electrodes on the scalp, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

Electroconvulsive therapy may have developed a negative reputation from its past use when the therapy might have been used inhumanely, with high doses of electricity, without anesthesia, and over many more treatment sessions than it is given today. [5 Controversial Mental Health Treatments]

There's definitely a stigma attached to electroconvulsive therapy, and many people may be frightened of it even in its uses today, Podolsky said. But in modern medicine, ECT is used for people with a condition called treatment-resistant depression, which is severe depression that has not improved with medication or other treatments.

Today, ECT is done under general anesthesia, and is typically given three times a week for three to four weeks. The treatment affects brain chemicals and nerve cells, and can produce changes in mood, sleep and appetite, according to information about ECT from the University of Michigan Health System Department of Psychiatry.

The most common side effects of ECT are memory loss, confusion, headaches and nausea.

Modern-day lobotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder

Lobotomies were a controversial surgical treatment for some forms of mental illness, including schizophrenia, manic depression and bipolar disorder, that became popular in the late 1930s and remained in steady use until around the mid-1950s. In some instances, the surgery was also inappropriately used for people with mental retardation, chronic headaches and anxiety, according to a medical historian who wrote an editorial on lobotomy published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2005.

During a lobotomy, a doctor drilled a small hole in a person's skull aimed at severing nerve fibers in the brain that connect the frontal lobe, the area that controls thinking, with other brain regions.

This procedure was thought to help improve a person's abnormal behavior, but often left people withdrawn, apathetic and childlike. It was commonly used in overcrowded mental institutions during the 1940s and early 1950s to quiet patients down, Podolsky said.

By the mid-1950s, with the advent of antipsychotic medications, which were a more effective remedy for mental illness, lobotomies were no longer needed, Podolsky said.

Today, a new wave of psychosurgeries is being done in some hospitals, and although these procedures are considered controversial much like lobotomies were, they may be more precise in targeting the brain tissue that is causing people's symptoms, according to a review study of psychosurgeries published in 2005 in the journal Brain Research Reviews. One of these brain surgeries is known as cingulotomy, which is used to treat people with severe obsessive compulsive disorder. During a cingulotomy, doctors destroy a small amount of brain tissue thought to be overactive.

Obsidian blades in surgery

In the Stone Age, scalpels with blades made from rock called obsidian, or volcanic glass, were used to bore a hole into the skull. These medical instruments had an extremely sharp cutting edge, and these days an obsidian scalpel is still used in a few situations. But obsidian tools are expensive compared with stainless-steel scalpels, and few manufacturers make them.

Obsidian blades are said to be at least 100 times sharper than stainless-steel surgical scalpels and there's some evidence that cuts made with them may heal more rapidly with less scarring. But an obsidian blade is also very thin and fragile, and surgeons cannot apply the same amount of force to this cutting tool as a steel scalpel or it may break and shatter its pieces into the wound. [Unlucky 7? Emergency Surgery Usually Means These Operations]

Obsidian blades are not FDA-approved for use in the U.S., although a small number of surgeons in other countries use them, often for very delicate procedures in cosmetically sensitive areas.

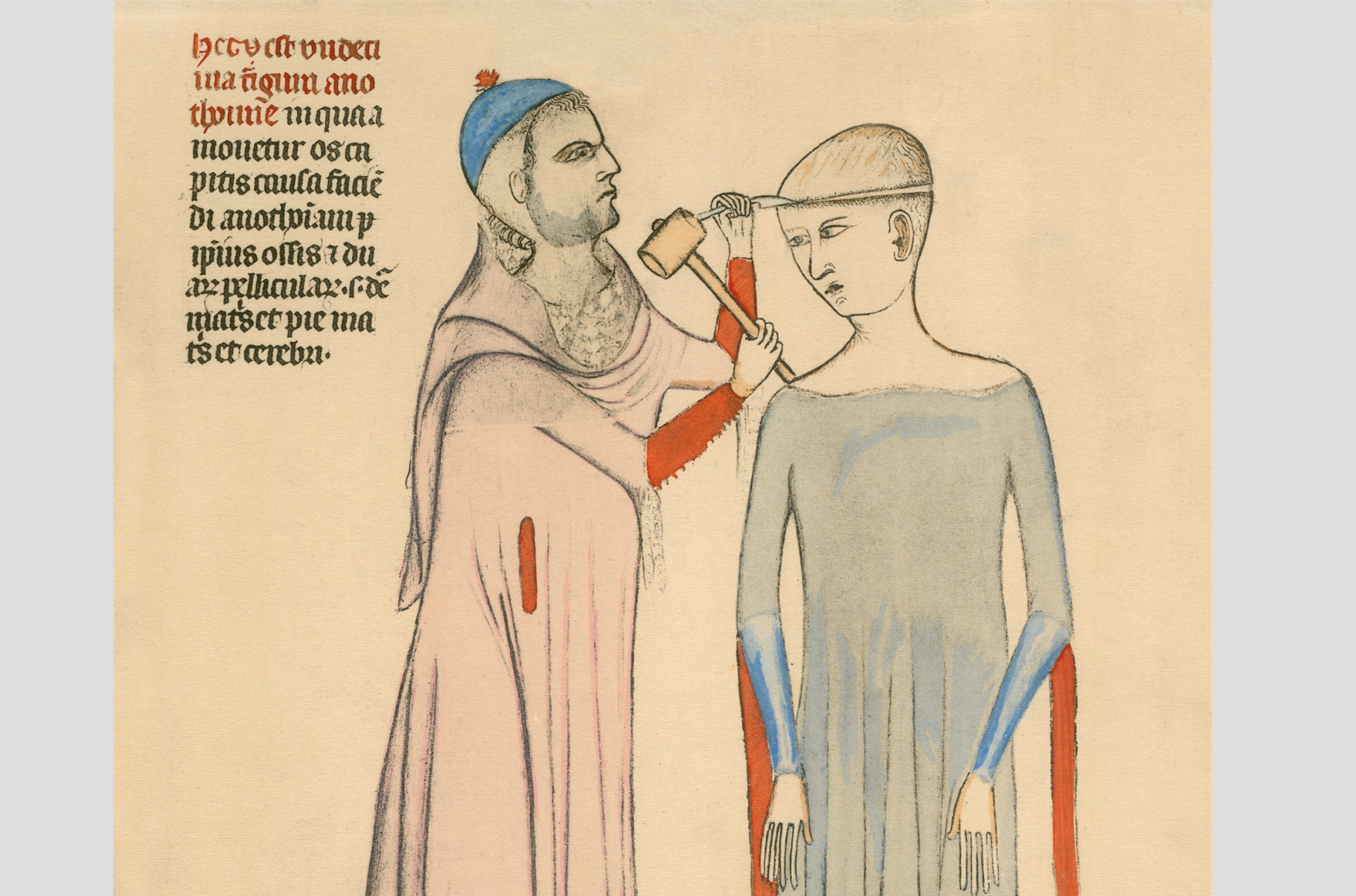

Trepanning

Trepanation is the oldest known surgical procedure, and dates back to the Stone Age. It involves making a hole in a person's skull.

Trepanning might have been done in ancient civilizations to rid a person of evil spirits believed to cause illness, or to treat conditions such as severe headaches, epilepsy, convulsions, head injuries and infections.

A version of trepanation is performed by neurosurgeons for very different reasons today, Podolsky said. These days, surgeons use the technique and different tools for drilling a small hole in the skull (but not into the brain itself) when there's internal bleeding due to trauma, such as from a car accident. Trepanning may also be used for a subdural hematoma, which is bleeding between the cover of the brain and the brain itself, which can commonly occur after an older adult suffers a minor head injury, or when a stroke has occurred, Podolsky said.

The modern-day use of trepanning helps to help relieve intracranial pressure, which prevents too much pressure from building up inside the skull, Podolsky said. Side effects of the procedure include a possible injury to the brain, as well as general risks from surgery, such as bleeding and infection, he said. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

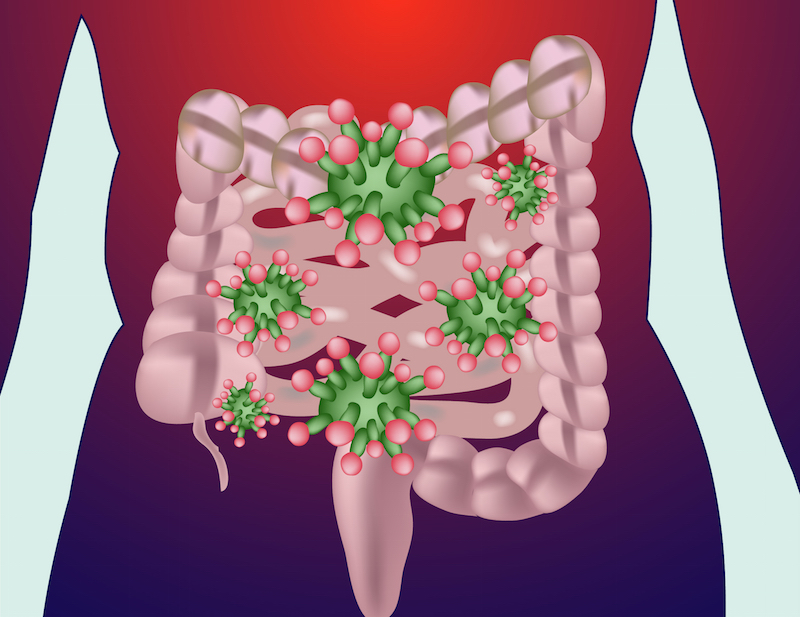

From "yellow soup" to fecal transplantation

A 4th century Chinese doctor first had the idea of giving a suspension that contained the dried stool from a healthy person by mouth as a treatment to someone with severe diarrhea or food poisoning. According to numerous accounts, this remedy may have been an ancient attempt at what is now called "fecal microbiota transplantation."

By the 16th century, another Chinese doctor used "yellow soup," a broth containing the dried or fermented stool of a healthy person as a treatment for severe diarrhea, vomiting, fever and constipation, several sources claim.

Today, stool transplantation, also called fecal microbiota transplantation, or FMT, is not done by spooning down "yellow soup." It does involve the transfer of stool from healthy donors to sick people, but the stool may be given by an enema or inserted through a tube into a person's stomach or small intestine, a process that introduces a healthy mix of bacteria to restore a better microbial balance in the gut. [The Poop on Pooping: 5 Misconceptions Explained]

"Poop transplants" may be used to treat people with recurrent Clostridium difficile (C.diff) infections, a bacterial infection that can be life-threatening. The symptoms of people who receive FMT get better within days, although their gut bacteria may undergo a dramatic change for at least three months after the procedure, according to a study presented in May at Digestive Disease Week, a gastrointestinal system research meeting, in San Diego.

Originally published on Live Science.

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus