Ear Maggots and Brain Amoebas: 5 Creepy Flesh-Eating Critters

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A 56-year-old Australian man is fighting for his life after becoming infected with a rare, flesh-eating "superbug" that caused giant wounds to develop on his thigh and stomach.

The man's condition is known as necrotizing fasciitis, and it's caused by a relatively well-known bacterium: Streptococcus, better known as Strep, according to a report by The West Australian, a local newspaper out of Perth. Some strains of the bacteria are potentially deadly, but they're not the only unusual things out there that can devour human flesh from the inside out.

Here are five pathogens and pests that feast on the human body.

Beastly bacteria

The Australian man infected with flesh-eating bacteria last week is one of many people around the world to fall ill every year from a particularly nightmarish pathogen known as Group A Streptococcus. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

These bacteria typically enter the body through open wounds and cause a condition known as necrotizing fasciitis, a rapidly spreading infection that kills the body's soft tissues, including skin and muscle. An estimated 400 people are diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis every year in Australia alone, The West Australian reported.

The Group A Streptococcus bacteria that cause flesh-eating disease are the same kind that sometimes cause other ailments, such as scarlet fever, impetigo (a type of skin infection), toxic shock syndrome and cellulitis, according to the National Institutes of Health. (Another strain of Strep bacteria causes strep throat.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the flesh-eating bacteria infect the fascia, or the connective tissue that surrounds muscles, blood vessels and nerves, the results can be deadly. Medical researchers estimate that about 25 to 30 percent of patients who contract the flesh-eating strain of Strep bacteria don't survive the infection.

Shoo, fly!

In 2013, a British tourist took home an unsavory souvenir from Peru: an earful of flesh-eating maggots. The wormlike creatures that doctors pulled from the woman's ear were the larvae of the New World screwworm fly (Cochliomyia hominivorax), which are indigenous to the Americas. Female screwworm flies lay their eggs in the exposed flesh of warm-blooded animals, including the flesh wounds of injured pets, the belly buttons of newborn livestock and the bodily openings of human beings.

The eggs of a female screwworm fly hatch within 24 hours of being deposited and begin to consume the flesh and bodily fluids of whatever host they have infested, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The parasitic larvae are lined with tiny ridges that help the maggots burrow deep into flesh. These features make the wormlike larvae look like tiny screws (hence their name).

The woman with the flesh-eating maggots brought them home with her from Peru in 2013. She first noticed there was something wrong when she heard a "scratching" sound inside her head and experienced shooting pains down the side of her face. After the pests were removed from her ear, the woman's symptoms improved, and only a small hole remained in her ear canal as a memento of her harrowing experience. [7 Absolutely Horrible Head Infections]

Bad-news bugs

Like the flesh-eating larvae of the screwworm fly, the babies of the human botfly (Dermatobia hominis) can also make your skin crawl. But unlike screwworm eggs, botfly eggs aren't deposited under a person's skin by a female botfly. Instead, the parasitic fly deposits her eggs on a host, such as a tick or mosquito, which then goes on to bite humans (or other animals). When that host, known as a vector, lands on a warm-blooded meal, the botfly eggs sense the change in temperature and hatch, entering the body of the animal at the site of the bite or sting.

D. hominis will stay under a person's skin, inside a layer of subcutaneous tissue, and feed on bodily fluids for about eight weeks before dropping out of its host's body and transforming into a fly. When they're inside the body, these maggots cause a condition known as furuncular myiasis, in which the site where the larvae entered becomes enlarged and inflamed, and oozes pus.

But removing the little maggots isn't all that difficult. A 2007 case study found that covering the larvae's site of entry with nail polish suffocates the creatures, which makes it easier to pull them from the skin.

Spider vs. man

If you don't like spiders, then this next fact probably won't help change your mind. Certain species of spiders dole out necrotizing, or "flesh-killing," bites. While many types of spider venom contain neurotoxins — which block nerve impulses to muscles and cause cramping, rigidness and disruption of the victim's bodily functions — other kinds of spider venom contain toxins that can cause necrosis, or the death of living tissues.

Cytotoxic venom can cause blistering around the site of a bite, which in turn may lead to open wounds and tissue death, according to the Australian Museum. Recluse spiders belonging to the group Loxosceles are perhaps the kind of spider most commonly associated with necrotizing venom. These spiders are indigenous to many parts of the world, including the United States, where the most common species, the brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa), inhabits some Midwestern and southern states.

While a recluse's bite can cause tissue death, such a side effect is rare, according to the University of California Integrated Pest Management Program, which states that only about 10 percent of brown recluse bites cause moderate or great tissue damage and scarring. And though necrotic wounds are often blamed on brown recluse spiders, these ghastly injuries are more often caused by other clinical conditions, like bacterial infections.

Misidentification of brown recluse bites is so common that Rick Vetter, a retired arachnologist at the University of California, Riverside, put together a comprehensive list of all the conditions that have been misdiagnosed as recluse bites in the medical literature. For instance, Vetter's list shows that a recluse "spider bite" may actually be something more serious, such as gangrene or Lyme disease.

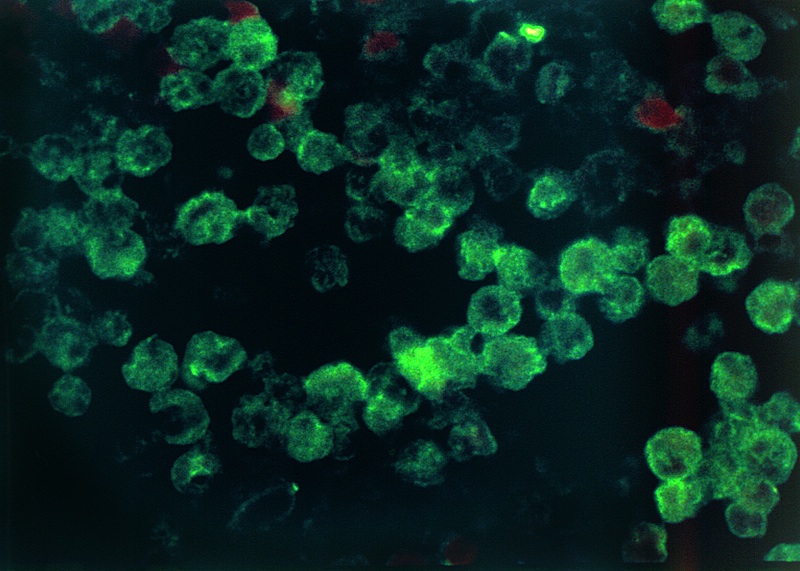

Amoeba attack!

In case flesh-eating worms and tissue-killing bacteria weren't enough to make you tremble, consider this: There is also a tiny organism that eats human brains. Naegleria fowleri is a microscopic amoeba that lives in warm, fresh water and enters the body through the nose. It passes through the sinus membranes into the olfactory bulb, where it reproduces and spreads through the brain, consuming brain tissue as it goes.

These horrific amoebas cause the brain to become infected, a condition known as primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), which leads to brain swelling and, in most cases, death. However, some people have survived encounters with N. fowleri, including a 12-year-old girl in Arkansas, who managed to fight off the brain-eating amoebas she contracted at a local water park in 2012. At the time, she was one of only three people known to have survived such an infection.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus