5 Controversial Mental Health Treatments

Introduction

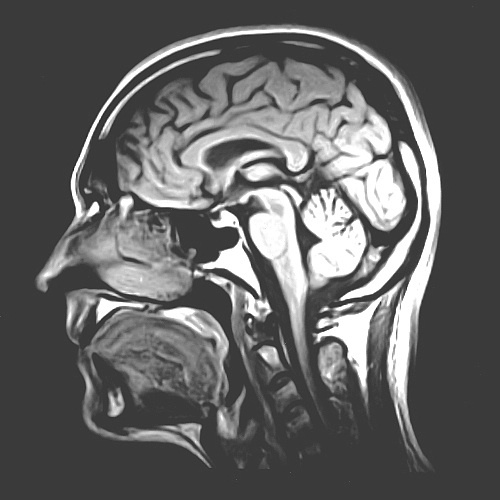

Psychiatric disorders are usually treated with talk therapy or medications, but when these treatments don't work, doctors and patients sometimes turn to less common, controversial procedures.

While these treatments, which include sending electric "shocks" through the brain, may sound extreme, some studies suggest that in certain patients, they can be very effective.

Here are five unconventional treatments for mental health disorders.

"Electroshock" Therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), first used in the 1930s, involves placing electrodes on the forehead and passing electrical currents through the brain in order to induce a seizure lasting 30 to 60 seconds.

The treatment is controversial, and in the early years of the therapy, patients were not given anesthesia, and high levels of electricity were used.

Today, the therapy is safer, because patients receive anesthesia and electricity doses are much more controlled, according to the Mayo Clinic. Still, the treatment can impair short-term memory and, in rare cases, cause heart problems.

Because of these potential side effects, ECT should never be used as a first line therapy. But, for people who have tried other treatments and have seen no improvement in their symptoms, the treatment can be very effective: 75 to 85 percent of patients who receive ECT recover from their symptoms, experts say.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

ECT is used to treat patients who are severely depressed and at risk for suicide, and in some cases, it is used to treat schizophrenia and severe mania.

Deep Brain Stimulation

Deep brain stimulation, which involves implanting a device that sends electrical impulses into the brain, is being investigated as a treatment for severe obsessive compulsive disorder, depression and drug addiction.

The therapy is already approved for treatment for tremors in Parkinson's disease and dystonia. In 2009, the Food and Drug Administration approved deep brain stimulation for treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), although patients are required to have tried other treatments for at least five years before they can qualify for the procedure.

After deep brain stimulation, some patients with OCD show improvements in mood, such as a decrease in anxiety, and have a better response to behavior therapies that weren't working before.

However, experts caution that the treatment is not a cure.

"What DBS really does is make you into an average OCD patient," Dr. Benjamin Greenberg, a psychiatrist at Brown University and at Butler Hospital in Providence, R.I., told LiveScience in a 2010 interview.

Related: OCD obsessions often come with physical sensations

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Another unconventional treatment for depression is transcranial magnetic stimulation. The treatment uses magnetic fields to change the activity in certain regions of the brain. It involves placing an electromagnetic coil on the forehead, and does not require surgery, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Researchers don't know how the treatment works, but it's thought that the magnetic fields stimulate regions of the brain involved in mood control, the Mayo Clinic says.

In 2008, the procedure was approved as a treatment for depression in those who haven't responded to other therapies.

Side effects include headaches, facial twitching, light-headedness, and less commonly, seizures and hearing loss.

Psychosurgery

Brain surgery for mental disorders, called psychosurgery, has been practiced since the 1930s, although it is very controversial. Early surgeries, such as lobotomies practiced in the 1940s and 50s, had serious side effects, including personality changes.

The practice of psychosurgery declined after psychiatric medications became available, although a small number of centers today continue to perform psychosurgery procedures.

A study published in June 2013 looked at the effects of a type of psychosurgery called bilateral capsulotomy, which damages the tissue in a part of the brain called the internal capsule, as a treatment for a small number of patients with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Nearly half of patients showed some improvement in their OCD symptoms, although 10 percent experienced serious side effects, including paralysis.

Magic mushrooms

The hallucinogen found in magic mushrooms, called psilocybin, may help treat psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety and addiction.

In a small 2011 study, more than half of people who received a moderate dose of psilocybin reported a "mystical" experience, the type believed to have the greatest long-term psychiatric benefits. Just 5 percent reported experiencing side effects, such as extreme fear (paranoia) or anxiety.

Even a year later, 83 percent of participants said the mystical experiences had increased their well-being.

Psilocybin is being studied as a treatment for terminally ill patients who experience depression and anxiety, and for those with hard-to-treat addictions, including alcoholism, researchers say. A 2010 study suggested that psilocybin could reduce anxiety and improve mood in people with terminal cancer.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.