Inflation could hit your mental health as much as your wallet, psychologists say

Why the rise in cost of living today is leading to depression and more.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

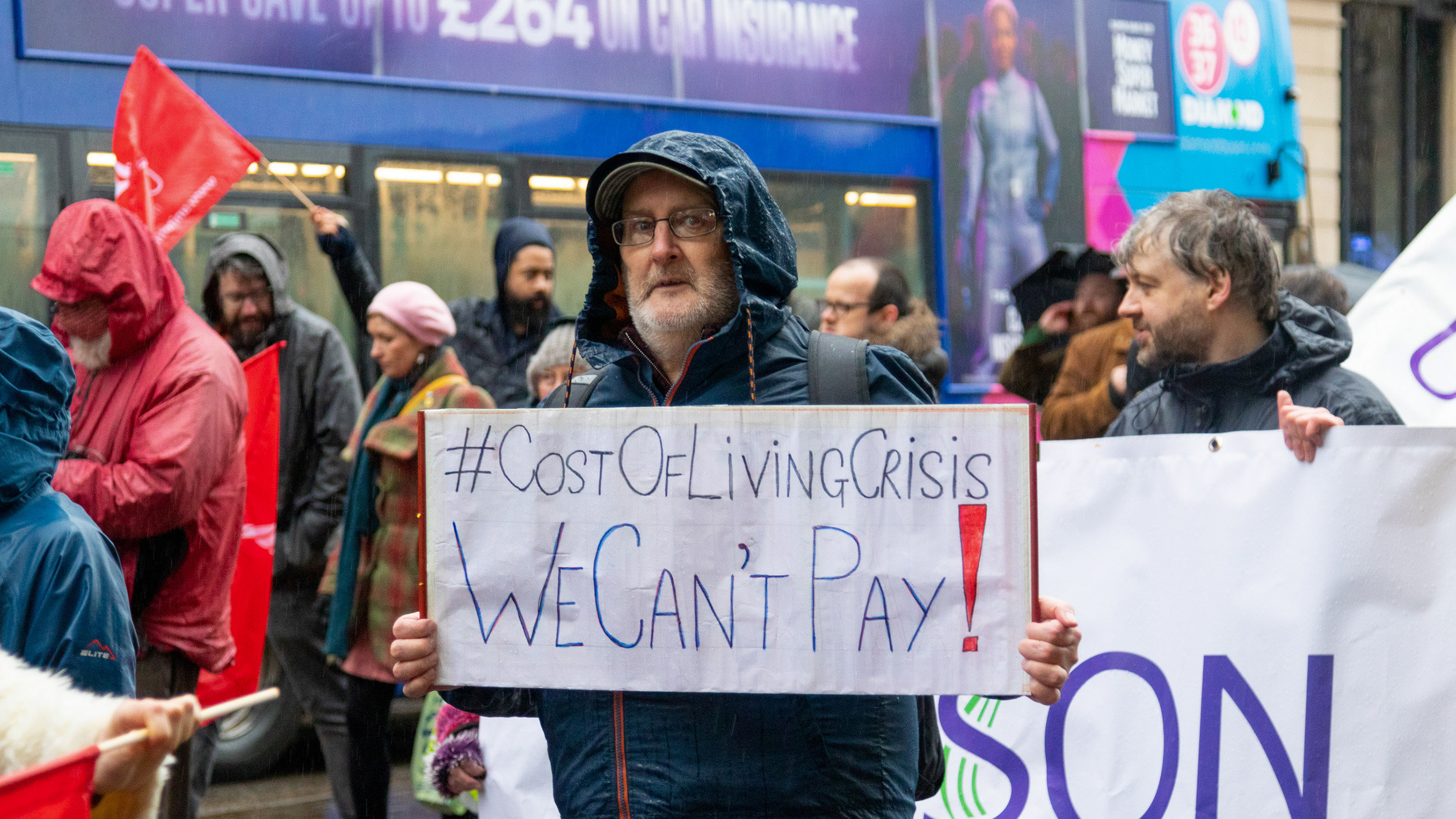

The cost of living is rising, creating new economic uncertainty on the tail end of a very uncertain two years. Experts say the result could be more mental strain, stress and anxiety.

Inflation in the U.K. hit a 30-year high in January, with consumer prices up 5.5% from the previous year. The U.S. saw consumer prices rise 7.5% year-over-year as of January, the biggest annual increase in 40 years.

In and of itself, inflation is not necessarily tied to declines in mental health. The impact on individuals depends heavily on their financial situations: For example, someone deeply in debt can benefit from inflation because each dollar they have to pay back is worth less, effectively shrinking their debt. But if that person's income doesn't rise along with inflation, they may end up in worse financial shape. And people whose incomes mostly go to necessities like food and gasoline — low-wage earners — tend to suffer most of all when inflation is high.

Related: 10 simple ways to ease anxiety and depression

The result of continuing inflation, then, could be to deepen economic inequality, a problem that existed well before the pandemic, said Lisa Strohschein, a sociologist at the University of Alberta who studies stress, family dynamics and health, including the effects of financial strain.

"Growing economic inequality has been a significant and long-term issue," Strohschein told Live Science. "And we now live in a world where the pandemic has made some people more wealthy than they already were, but for people who are at the bottom, they have never been more insecure."

The impacts of economics

Economic indicators don't occur in a vacuum, so linking a particular measure to mental health isn't always possible. But there are some things researchers know well. One is that economic inequality, or a large schism between haves and have-nots, is bad for a population's health, including mental health.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In a study published in the journal World Psychiatry in 2018, researchers reviewed 26 studies on income inequality around the world and found that two-thirds said that as income inequality rose, so did depression. A statistical re-analysis of 12 of those studies showed that people in highly inequitable societies were about 1.2 times more likely to experience depression compared with people in more equal societies. Unequal societies also have higher rates of schizophrenia, studies have found, perhaps because inequality decreases social cohesion and raises chronic stress for vulnerable people.

Unemployment is also hugely damaging to individuals' mental health. The Holmes-Rahe Life Stress Inventory, a psychological tool used to gauge how likely it is that someone experiences health impacts from stress, ranks losing a job as the eighth-most stressful life change that can happen to someone. Many different studies have found negative impacts of being unemployed, ranging from symptoms of anxiety and depression to low self-esteem and loss of well-being. In one 2009 paper in the Journal of Vocational Behavior, researchers describe how they re-analyzed data from more than 300 studies on unemployment and mental health; they found that 34% of people who were unemployed experienced psychological symptoms, compared with 15% of the employed. Blue-collar workers were hit the hardest.

Related: 10 energy-saving life hacks: How to save on electricity bills & more

Inflation is more complicated. For the low-earning households, the rising cost of goods is a source of insecurity. A recent Washington Post investigation looked at how inflation is hitting low-income Americans and found people struggling to afford basic groceries and other necessities. In contrast, the wealthiest segment of society has more of a financial cushion to absorb rising costs, as well as investments that tend to outperform inflation in the long run.

Financial strain hasn't been as big of a problem in the pandemic as labor market upheaval might suggest. People spent less and may have saved more, said Scott Schieman, a sociologist at the University of Toronto. But inflation will change that picture.

"Inflation will make the actual level of pay seem less adequate," Schieman told Live Science. "And for lower-earning households, that starts to make the anxiety and strain creep up."

Schieman's research involves long-running nationally representative surveys of American and Canadian workers. In the U.S. in January and February, he said, more than half of workers said they felt their job didn't pay them enough to make ends meet. That's part of a trend going back at least 20 years, he said. Feeling underpaid is linked to worse job satisfaction, he said, which may explain why workers are quitting their jobs in large numbers. For those who stay — or who can't find a better-paying position — the financial crunch can have emotional echoes.

"Feeling underpaid and having insufficient income from one's main job is a chronic source of stress that has links to anger and resentment," Schieman said. "That dampens positive views about other aspects of the job that might otherwise be seen as good things — like autonomy or challenge."

To stave off inflation, governments may raise interest rates, which puts a brake on borrowing and spending. This can have negative impacts on some subgroups, though. For example, a 2018 study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders found that people who are deeply in debt may struggle psychologically when interest rates rise. The heavily indebted have a higher rate of mental health problems than the general population. For this group, the research found, a 1% increase in interest rates can lead to a 2.6% increase in the risk of experiencing a psychiatric disorder.

Cumulative stress

Inflation has risen in the past, Strohschein said, and that hasn't always translated to major financial and mental strain. Wages often rise along with inflation, easing some of the stress for consumers, she said. But higher cost of living is just one stressor among many that people have experienced since the COVID-19 pandemic started. That means that many people are already at the end of their ropes.

"People can handle one stressful thing, but when [stressors] begin to accumulate, that's what puts people over the edge. It's that straw that broke the camel's back," Strohschein said.

In the U.K., wage growth is not currently keeping up with the pace of inflation, especially among frontline workers in education and health, The Guardian reported. Frontline workers are among those hit the hardest by the emotional strain of working outside the home and caring for others during the pandemic.

There is a psychological impact to inflation beyond its financial impact, Schieman said.

"Things just feel worse, there's a sense of uncertainty and a loss of control that goes with it," he said. "And there's a sense it could be worse down the road. All of these things dampen our sense of satisfaction and undermine emotional well-being."

This feeling of fear about the future may be hitting young people hard. Though older people are at a far higher risk of death from COVID-19, surveys suggest that younger people took the biggest psychological hit during the pandemic. Research conducted in the U.S. by psychologist Jean Twenge of San Diego State University found that in 2020, adults 18 to 44 saw the worst impacts on mental health, while adults over 60 were least affected psychologically, Live Science previously reported. Twenge speculated that younger people were affected more by business closures and job loss.

The youth mental health crisis has only continued. University students have missed opportunities for socialization and career networking due to pandemic precautions, Strohschein said, and many are feeling uncertain or even hopeless about their prospects.

"For young people, it's about the ways in which they make the transition to adulthood and their fears for their future," she said. These fears are likely well-grounded, she added, as the Great Recession of 2008 did have long-lasting impacts on Millennials, the generation that was launching into adulthood when that financial crisis hit. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Millennials delayed marriage and home buying due to high levels of student debt and high unemployment during the recession. A similar pattern could be seen in today's young adults, Strohschein said.

"The ways in which young people today are progressing through these really formative years and making decisions about what they will do with their lives, I think are going to be with us for a long, long time," she said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus