Lobotomy: Definition, procedure and history

Lobotomies have always been controversial, but they were widely performed for more than two decades to treat mental illness.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Lobotomy, also known as leucotomy, is a neurosurgical operation that involves permanently damaging parts of the brain's prefrontal lobe, according to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Introduced in the mid-20th century, lobotomies have always been controversial, but were widely performed for more than two decades as treatment for schizophrenia, manic depression and bipolar disorder, among other mental illnesses.

Lobotomy was an umbrella term for a series of different operations that purposely damaged brain tissue in order to treat mental illness, said Dr. Barron Lerner, a medical historian and professor at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York.

"The behaviors [doctors] were trying to fix, they thought, were set down in neurological connections," Lerner told Live Science. "The idea was, if you could damage those connections, you could stop the bad behaviors."

When lobotomy was invented, there were no good ways to treat mental illness, and people were "pretty desperate" for any kind of intervention, Lerner said. Even so, there were always critics of the procedure, he added.

When was the first lobotomy?

Even before the first lobotomy, doctors were manipulating the brain to change behavior. Beginning in the late 1880s, the Swiss physician Gottlieb Burkhardt removed parts of the cortex of the brains of patients with manic agitation, auditory hallucinations and symptoms of schizophrenia. Burkhardt noted in an 1891 paper that the surgery calmed his patients, though some suffered complications such as motor weakness, sensory aphasia (inability to understand speech, writing or tactile symbols) and epilepsy, and one patient died five days after the procedure, researchers reported in 2008 in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz is credited with officially inventing the lobotomy in 1935, for which he shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1949 (later, a movement was started to revoke the prize, unsuccessfully).

Moniz's breakthrough was inspired by lobotomy-like procedures that Yale neuroscientist John Fulton and his colleague Carlyle Jacobsen performed on chimpanzees. They removed both frontal lobes in a female chimpanzee who had previously displayed anger and frustration if she made a mistake while performing tasks in experiments; after the surgery, the chimp became more cooperative and did not show signs of frustration, scientists wrote in 2014 in the Singapore Medical Journal.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Later that year, Moniz and his colleague Almeida Lima performed the first human lobotomy experiments, operating on 20 people. The doctors targeted the patients' frontal lobes because that brain region is associated with behavior and personality.

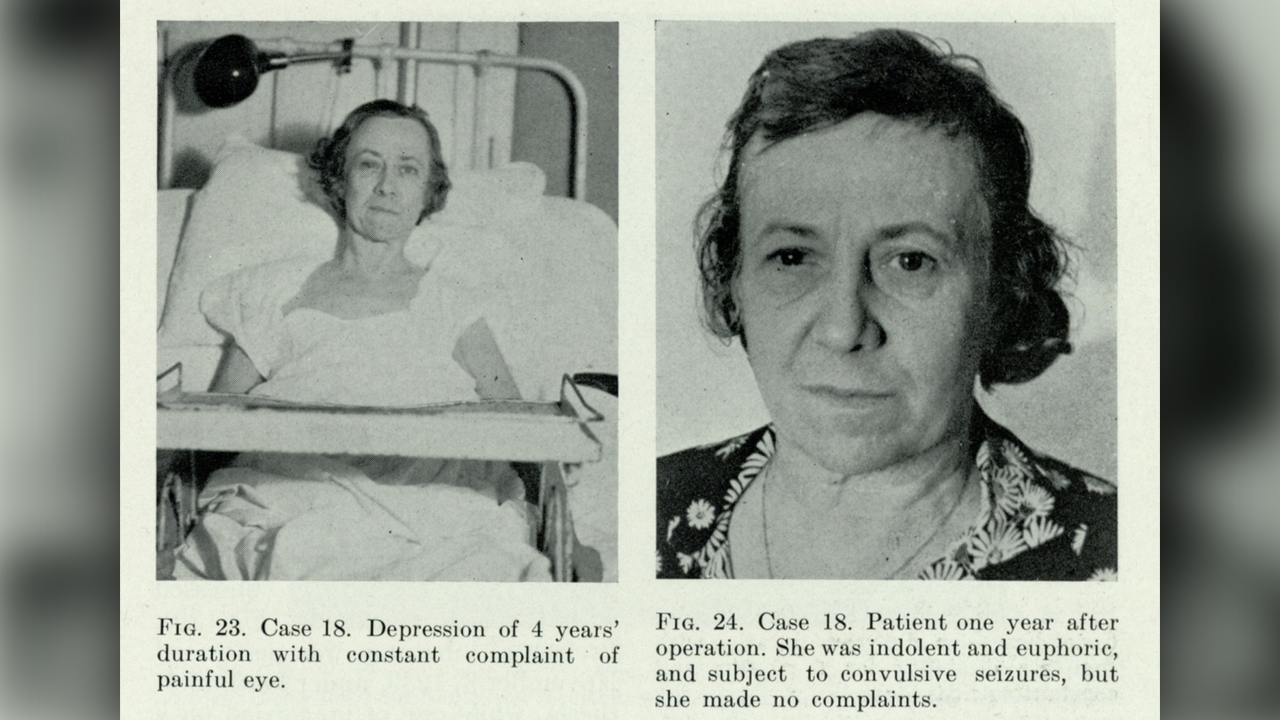

Moniz reported the surgeries as a success in treating patients with conditions such as depression, schizophrenia, panic disorder and mania, according to an article published in 2011 in the Journal of Neurosurgery. But the operations had severe side effects, including increased body temperature, vomiting, bladder and bowel incontinence and eye problems, as well as apathy, lethargy and abnormal sensations of hunger, among others. The medical community was initially critical of the procedure, but nevertheless, physicians started using it in countries around the world.

How is a lobotomy performed?

Moniz's first lobotomy procedures involved cutting a hole in the skull and injecting ethanol into the brain to destroy the fibers that connected the frontal lobe to other parts of the brain. Later, Moniz developed a surgical instrument called a leucotome, which contains a retractable loop of wire that, when rotated, cuts a circular lesion in brain tissue.

Italian and American doctors were early adopters of the lobotomy. American neurosurgeons Walter Freeman and James Watts were the first to perform the procedure in the United States in 1937, making "nine cores in the white matter of each frontal lobe" of a 59-year-old patient, according to a 2015 report in the journal The Lancet. They adapted Moniz's technique to create the "Freeman-Watts technique" or the "Freeman-Watts standard prefrontal lobotomy," in which a surgeon drilled holes in the patient's skull, then inserted and rotated a knife to destroy brain cells, targeting connections between part of the prefrontal lobes and a region in the thalamus, which is a grey-matter structure toward the center of the brain, The New York Times wrote in 1994 in Dr. Watts' obituary.

"Freeman thought psychosis was the result of excessive self-reflection — thoughts that circled back on themselves over and over again," Miriam Posner, assistant professor in the information studies department at UCLA, said in 2019 in the National Library of Medicine's History of Medicine Lecture Series at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

"He was being literal when he said lobotomy was a way of cutting those endlessly circling thoughts off within the brain," Posner said.

The Italian psychiatrist Amarro Fiamberti developed a procedure that involved accessing the frontal lobes through the eye sockets; that procedure would inspire Freeman to develop the transorbital lobotomy in 1945, a method that would not require a traditional surgeon or operating room, researchers reported in 2019 in the journal Frontiers in Neuroscience. The technique involved using an instrument called an orbitoclast — a long, slender instrument modeled after an ice pick — which the physician would insert through the patient's eye socket using a hammer. They would then move the instrument side-to-side to separate the frontal lobes from the thalamus, the part of the brain that receives and relays sensory input.

Transorbital lobotomies did not require anesthesia and were quicker to perform than standard lobotomies; consequently, surgeons across Europe and America performed tens of thousands of these procedures over the next two decades, according to the 2019 study. Freeman himself performed at least 3,000, and possibly as many as 5,000 lobotomies, according to the obituary in the Times.

"He traveled around the country, doing multiple lobotomies in a day," Lerner said. "He absolutely did this for way too long." Freeman performed his last lobotomy in 1967; it was his third such procedure on the patient, a woman named Helen Mortensen, NPR reported. She died of a brain hemorrhage soon after, and Freeman was banned from performing surgery, according to NPR.

What happens after a lobotomy?

While a small percentage of people supposedly showed improved mental conditions or no change at all, for many patients, lobotomy had negative effects on their personality, initiative, inhibitions, empathy and ability to function on their own, according to Lerner.

"The main long-term side effect was mental dullness," Lerner said. People could no longer live independently, and they lost their personalities, he added.

Mental institutions played a critical role in the prevalence of lobotomy. At the time, there were hundreds of thousands of mental institutions, which were overcrowded and chaotic. By giving unruly patients lobotomies, doctors could maintain control over the institution, Lerner said.

That's exactly what unfolds in the 1962 novel and 1975 film "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," in which Randle Patrick McMurphy, a violent but sane man who declares himself insane to avoid a prison sentence, is sent to mental hospital and given a lobotomy that leaves him mute, unresponsive and vacant-eyed.

"Usually things in movies are exaggerated," Lerner said. But in this case, it was "disturbingly real," he said.

Are lobotomies performed today?

Lobotomies declined in popularity in the 1950s, as their undesirable side effects became more well-known. Criticism of the procedures also grew among medical professionals who said the doctors who performed lobotomies were not neurosurgeons, neglected to report negative outcomes for many of their patients, and overall had "a lack of scientific rigor," according to the Frontiers in Neuroscience study.

"It also became apparent that some institutionalized or incapacitated patients were lobotomized without informed consent, and procedures may have been performed on prisoners to address dysfunctional behavior as opposed to mental illness," the study authors reported.

By the mid-1950s, scientists had developed psychotherapeutic medications such as the antipsychotic chlorpromazine, which was much more effective and safer for treating mental disorders than lobotomy. Nowadays, mental illness is primarily treated with drugs and psychotherapies. In cases where drugs or talk therapy are not effective, people may be treated with electroconvulsive therapy, a procedure that involves passing electrical currents through the brain to trigger a brief seizure, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Lobotomy is rarely, if ever, performed today, and if it is, "it's a much more elegant procedure," Lerner said. "You're not going in with an ice pick and monkeying around." The removal of specific brain areas (psychosurgery) is reserved for treating patients for whom all other treatments have failed.

Additional lobotomy resources

- Nobelprize.org: Controversial Psychosurgery Resulted in a Nobel Prize

- PsychCentral: The Surprising History of the Lobotomy

- NPR: "My Lobotomy": Howard Dully's Journey

This article was updated on Oct. 13, 2021 by Live Science senior writer Mindy Weisberger.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus