Dinosaur Tracks Reveal Odd Mating Dance

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Did dinosaurs shake a tail feather? Some meat-eating theropods used fancy footwork to attract their mates, leaving behind their fox-trotting tracks in rocks millions of years ago.

An analysis of the newfound marks suggests they are the first known evidence of a type of mating display behavior known as "scraping," common in modern ground-nesting birds. The dinosaur lads may have performed their paleo-numbers in groups for a (hopefully) swooning female audience, the researchers say.

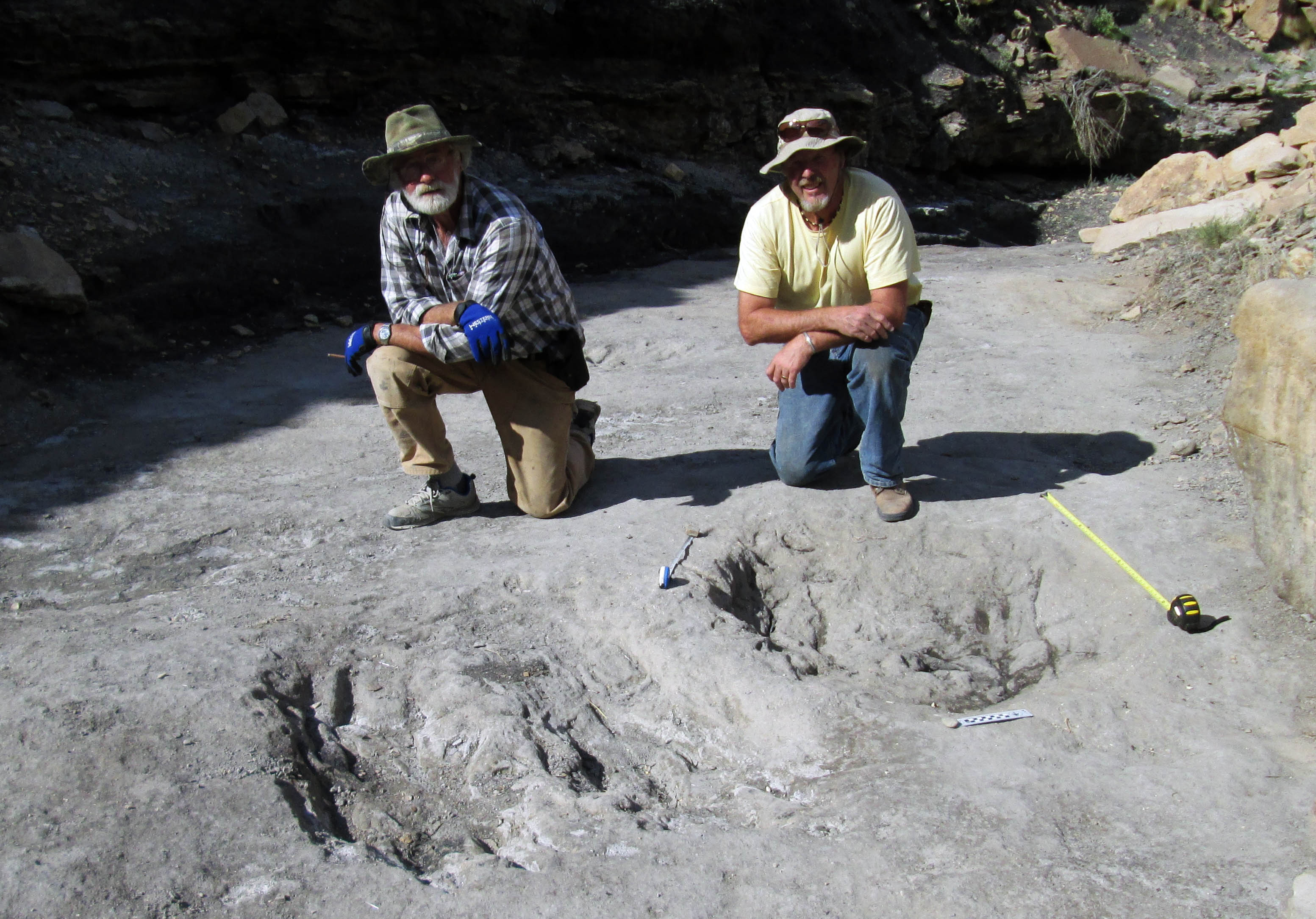

Paleontologists found scores of these "scrapes," areas in the rock that were shallowly scarred by multiple scratch marks. These collections of marks, each of which averaged about 6.6 feet (2 meters) in length, were scattered across four different Cretaceous sites in Colorado. The site locations, described by the study's authors as "spectacular," are crisscrossed with numerous dinosaur trackways — consecutive footprints made by the same animal. [Photos: Thousands of Dinosaur Tracks Along Yukon River]

Surprising scrapes

Martin Lockley, co-author of the study and emeritus professor of geology at the University of Colorado, Denver, told Live Science that these scrape marks were unlike anything the scientists had seen before. When Lockley and his colleagues first noticed the marks, the prints were partially covered with sand. "We started cleaning them off and taking a closer look at them, and we knew right away that there was something unusual about them," Lockley said. More and more of these scrape traces emerged as their investigation widened, eventually revealing about 60 of them in one of the sites.

It soon became clear that these unusual scrapes were connected to the dinosaurs whose tracks marched through the area. "We were calling them 'digging dinosaur' traces," Lockley said. "They were obviously made by the feet of dinosaurs, because we could see the claw marks. We could see two sides, a left and a right trough, with a ridge in the middle," he said.

Some of the scrape traces included the trademark three-toed footprint of a theropod, a group of bipedal and mostly carnivorous dinosaurs, further cementing the strange marks' connection to dinosaur creators. According to Lockley, that's when things really got interesting. "It was like, 'OK, we know what kind of dinosaur made them — what were they doing?'"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Paleo-detectives

Like television's Crime Scene Investigation (CSI) detectives, the scientists faced the challenge of recreating a scenario based on the clues left behind. And like detectives, they considered — and ruled out — a number of possibilities.

Were the dinosaurs digging for water? Not likely, Lockley said. The environment in that part of North America was very wet during the Cretaceous, and water would have been plentiful. Could they have been searching for food? Probably not; carnivorous theropods wouldn't have scratched around in the dirt looking for roots or other vegetation, Lockley explained. And there's no evidence suggesting that floods at the time buried carcasses that the theropods might have dug up and scavenged, he added.

That's when Lockley and his colleagues realized that they might find an explanation for these extinct dinosaurs' behavior in the behavior of "dinosaurs" alive today — modern birds.

Perhaps the scrapes were signs of nest building? Existing fossil evidence shows that theropod dinosaurs, like birds, built nests and brooded their eggs. But the study authors were doubtful, because the marks and troughs in the scrapes would likely have been worn smooth by weeks of continued use, as the dinosaurs brooded their eggs and reared their young. And the variable shapes and haphazard placement of the scrapes didn't match up with the more regular nest shapes and spacing in known dinosaur nesting colonies. [Image Gallery: Dinosaur Daycare]

Dancing like a bird

But when the scientists reviewed accounts of birds' mating display behavior, they hit pay dirt. Descriptions of activity called "nest scrape display" and "pseudo nest building" seemed to produce similar marks to the ones that they found.

"During the breeding season, the males start to get excited and show off to their mates by scratching to say, Look, I can build a nest!" Lockley told Live Science. "And they get so excited that they scratch, and move along and scratch again — they make dozens or hundreds of scratches in a short period of time."

The "nest scrape" explanation, Lockley said, fit well with the Colorado scrape marks. In the study, the researchers point to a "long and diverse" list of birds that perform nest scrape displays, including puffins, a New Zealand parrot, and seven species of shorebirds. And this type of behavior carries across many branches in the bird family tree, according to Paul Sweet, manager of the Ornithology Collections at the American Museum of Natural History.

Sweet, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science that male sage grouse will gather season after season in a "lek," an open area where they perform high-energy mating displays that can include strutting, fanning their tails and "trying to make themselves look as big as possible," Sweet said. [Animal Sex: How Did Dinosaurs Do It]

According to the researchers, the four sites where they found the scratch marks could have been leks where groups of theropod males would gather to strut their stuff for an appreciative female audience. The scratches they left behind provide the first physical evidence linking dinosaur mating display behavior to that of living birds, the scientists said.

Lockley, who has devoted decades to the study of dinosaur trackways, told Live Science that more examples of this fancy footwork are likely to be discovered, now that paleontologists will be looking for them.

"It seems like every five to 10 years there's a new category of evidence that comes to light, and then it's like, 'Oh, it's everywhere, why didn't we find this before?'" Lockley said. "I wouldn't be surprised if we have dozens of these sites in a few years."

The findings were published online today (Jan. 7) in the journal Nature Scientific Reports.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus