Ancient Footprints May Show Dinosaur Duo Strolling Along the Beach

About 142 million years ago, two carnivorous dinosaurs wandered along a beach and left their large footprints behind in the sand, a new study finds.

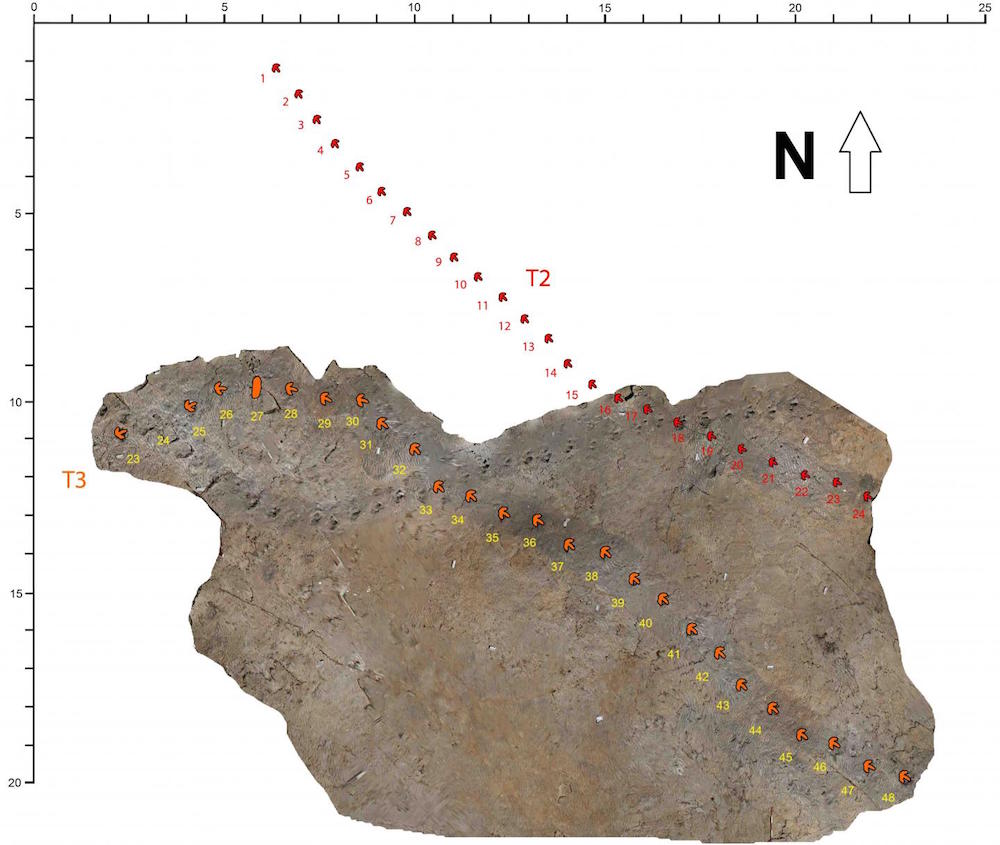

These footprints, now fossilized, are helping researchers understand what types of dinosaurs lived in what is now modern-day northern Germany. The tracks show that one dinosaur was large, and the other small. Their prints suggest they walked at a slow, strolling pace — about 3.9 mph (6.3 km/hour) for the large one and about 6 mph (9.7 km/h) for the little one.

At some points, the small dinosaur began trotting, possibly to keep pace with the large one. The footprints also indicate the dinosaurs skid here and there, likely slipping on the wet sand, said study researcher Pernille Troelsen, who earned her master's degree in biology from the University of Southern Denmark in June.[Paleo-Art: Dinosaurs Come to Life in Stunning Illustrations]

The dinosaurs' leisurely paces are slow, given that scientists estimate carnivorous dinosaurs could run faster than about 25 mph (40 km/h), Troelsen said.

Fancy footprints

For the past 200 years, researchers have flocked to Germany's Bückeberg Formation to study fossilized dinosaur footprints and tracks. Many are found in the formation's fine-grained quartz sandstones, but Troelsen chose to study the two tracks — about 50 footprints in all — preserved in a silty mudstone layer.

Her biology background gave her a different perspective from that of geologists, who have also studied the two trackways, she said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"As a biologist, I can contribute with knowledge about behavior of the individual animals," Troelsen said in a statement.

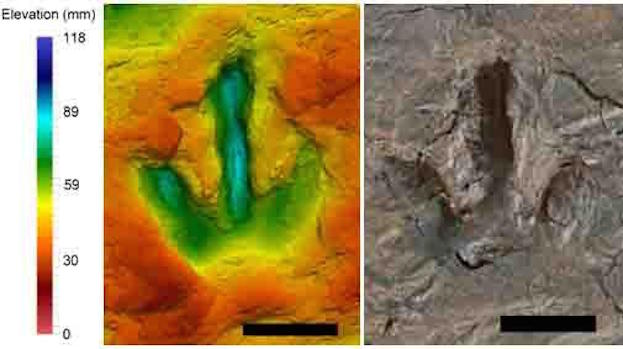

She started by analyzing the footprints. The large dinosaur's feet measured an average of 13.5 by 14.3 inches (34.4 by 36.4 centimeters) — larger than a U.S. man's size 15 shoe — and the small theropod's prints measured an average of 9.3 by 9.3 inches (23.5 by 23.5 cm), or about a U.S. man's size 6 shoe, Troelsen told Live Science in an email.

Further analysis suggests the animals stood about 5.2 feet (1.6 meters) and 3.6 feet (1.1 m) at hip height, for the large and small dinosaur, respectively, and were likely a species of meat-eating dinosaur within the Megalosauripus genus.They were about the same size as Velociraptor, and were agile hunters that walked and ran on two legs, she said.

Sometimes, the little dinosaur crossed its legs as it walked along the beach, though it's unclear why. Troelsen floated several ideas; perhaps the little theropod lost its balance because the sand was slippery or a gust of wind blew it aside. Or, maybe it found some interesting prey, or wanted to keep up with the big carnivore, she said.

"If so, this may illustrate two social animals, perhaps a parent and a young," Troelsen said in the statement.

Other studies suggest that several dinosaur species were social animals, and possibly hunted together and had dinosaur "daycares" in which adults cared for young together.

But it's impossible to tell whether these tracks were made at the same time.

"They may be many years apart, in which case it maybe reflects two animals randomly crossing each other's tracks," Troelsen said. "We can also see that a duckbill dinosaur (Iguanodon) has crossed their tracks at one time or another, so there has been some traffic in the area."

Researchers have found dinosaur footprints in a number of European countries, including England, northern Germany and Spain, most of them dated to the Lower Cretaceous period, from about 140 million to 145 million years ago, she said.

The findings have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, and were presented at the annual meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Paleontologists in Opole, Poland, on July 10.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.