Hurricane Patricia: How Big Can Tropical Cyclones Get?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

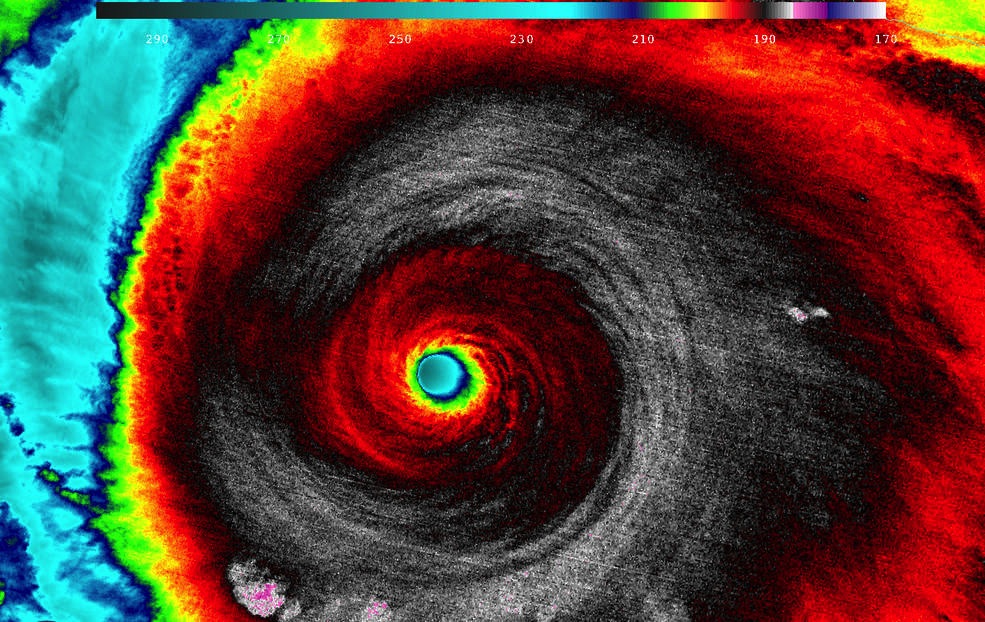

Hurricane Patricia is currently churning in the eastern Pacific Ocean, and weather forecasters are calling it the strongest hurricane ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere. Communities in southern Mexico, where the hurricane is expected to make landfall later today (Oct. 23), are already preparing for a "potentially catastrophic" storm. But with the right ingredients, more of these tempests could become monsters, experts say.

Hurricane Patricia is a Category 5 storm — the highest on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale that is used to gauge a storm's intensity — and is expected to have winds of nearly 200 miles per hour (325 km/h) with even higher gusts, according to the National Hurricane Center (NHC). After making landfall, the massive storm is expected to weaken and fall apart in the ensuing 36 hours.

According to the NHC, Category 5 hurricanes produce "catastrophic damage" that will destroy roofs and walls in framed homes. "Power outages will last for weeks to possibly months. Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months," NHC officials wrote on the agency's website. [Hurricanes from Above: See Photos of Nature's Biggest Storms]

Article continues belowCategory 5 storms typically have winds of at least 157 mph (252 km/h), but Patricia is special; earlier today, the NHC said Hurricane Patricia is the strongest hurricane on record in the area the center monitors, which includes the Atlantic. (Before Patricia, the strongest hurricane measured in the Western Hemisphere was Wilma in 2005, with top wind speeds of 175 mph, or 282 km/h.)

But there is mounting evidence that climate change is contributing to more intense hurricanes, due to warming oceans. A study published in July 2013 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that this century could see a 40 percent global increase in tropical cyclones that are Category 3 and higher.

So, with climate change fueling more monster hurricanes, how big can these storms get?

Hurricanes convert the energy of warm ocean air into powerful winds and waves. As such, warm water is the primary fuel for a hurricane, but the laws of physics dictate that hurricanes can't simply grow forever.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A 1998 calculation by Kerry Emanuel, a climatologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, suggested an upper limit of 190 mph (306 km/h) for hurricane winds. Emanuel and other hurricane researchers have predicted that wind speeds could increase about 5 percent for every 1 degree Celsius increase in tropical ocean temperatures, but there is still considerable debate. Some say it's unlikely that hurricane winds will exceed 200 mph (322 km/h).

Still, there have been other recorded non-hurricane wind records: One measurement, on April 12, 1934, atop Mount Washington pegged gusts at 231 mph (372 km/h). And in May 1999, Oklahoma scientists caught a tornado with winds of 318 mph (512 km/h).

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus