Global Ocean Acidity Revealed in New Maps

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

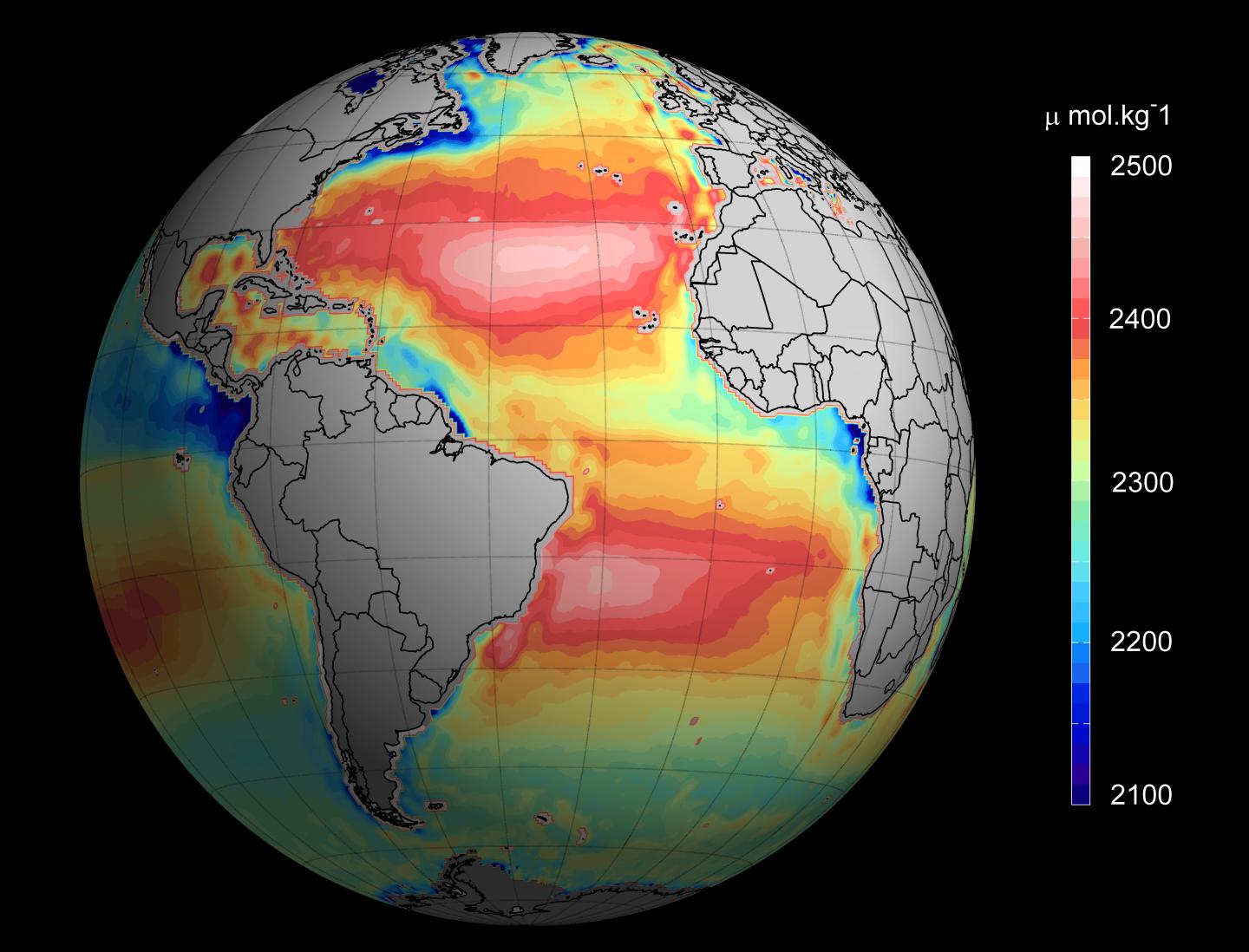

Ocean acidification can now be seen from space, highlighting an ongoing danger of climate change and revealing the regions most at risk.

Seawater absorbs about a quarter of the carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, that humans release into the atmosphere each year, mostly from the burning of fossil fuels, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). This process has slowed the warming of the globe, as all of that carbon is locked up in the ocean's "carbon sink" rather than floating freely in the atmosphere. But when seawater takes up carbon dioxide, it becomes more acidic. According to NOAA, the surface pH of the ocean has become 30 percent more acidic since the end of the Industrial Revolution.

That acidity is not necessarily evenly distributed, however, nor is it simple to measure. Most studies rely on physical measurements taken out in the open ocean from research vessels and buoys deployed from such vessels. These measurements are spotty and expensive to collect.

Now, scientists are turning an eye to the sky to complement on-the-ground data. Using satellite measurements, researchers at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom and their colleagues have created global maps of ocean acidity that show which areas are most affected.

"We are pioneering these techniques so that we can monitor large areas of the Earth's oceans, allowing us to quickly and easily identify those areas most at risk from the increasing acidification," study leader Jamie Shutler, a senior lecturer in ocean science at the University of Exeter, said in a statement.

Shutler and his colleagues used measurements available from existing satellites, such as NASA's Aquarius satellite and the European Space Agency's Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity sensor. They combined thermal camera imagery with salinity data to calculate acidification.

A map created from the results shows the variation apparent across the globe. The redder the color, the more alkaline, or basic — the opposite of acidic — the region is. The more basic the seawater, the more room it has to absorb carbon dioxide without becoming overly acidic. Open regions of the ocean show this resilience, while many coastal regions appear less alkaline. The northeastern United States looks particularly vulnerable — a finding that echoes 2013 research using on-the-ground measurements.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ocean acidification eats away at the shells of mussels, oysters and crabs, and baby oysters are already dying in some regions from it. These detrimental effects can carry up the food chain. Meanwhile, researchers worry about direct impacts on nonshelled ocean life as well. A 2013 study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B found that fish kept in acidic water acted more skittish than fish in normal seawater, which could affect their survival in the wild.

The new research is detailed in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus