Ebola vs. Hemorrhagic Fever: What's the Difference?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

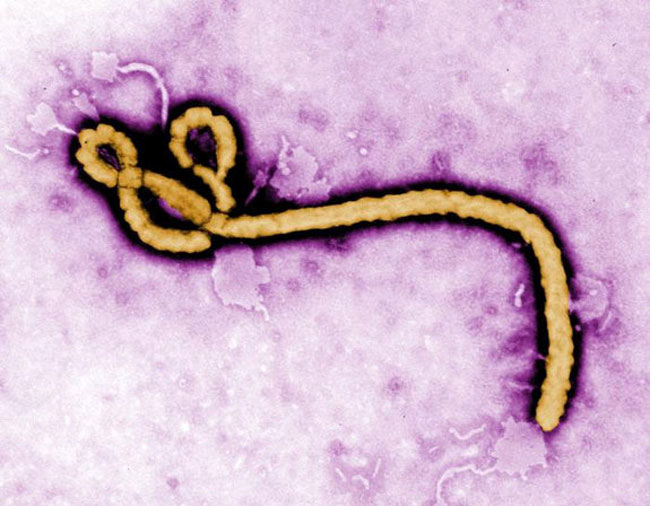

Ebola's most notorious symptom may be hemorrhagic fever, but the virus is actually one of many that can cause the hallmark bleeding from the nose, mouth, ears and other places.

Collectively known as viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs), these illnesses typically cause fever as well as extreme dysfunction in the body's network of blood vessels, which can result in profuse bleeding.

The hemorrhaging associated with VHFs can arise from a number of different factors depending on which virus a person is infected with, said Alan Schmaljohn, a virologist and professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

In the case of people with Ebola, hemorrhaging occurs when the virus infects the liver, affecting the body's ability to make blood-clotting proteins and causing blood vessels to leak. But other viruses may cause hemorrhaging by depleting the body's supply of platelets, which stop bleeding, Schmaljohn told Live Science. [5 Things You Should Know About Ebola]

Ebola is one of several members of the Filovirus family of viruses that can cause hemorrhagic fevers, and there are at least three other families of viruses that also cause hemorrhagic fevers, including Bunyaviruses, Flavaviruses and Arenaviruses, Schmaljohn said.

For the most part, there are no treatments available for people with any type of viral hemorrhagic fever, although one acute viral disease, yellow fever, can be prevented with a vaccine.

What these viruses have in common

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

All of the virus families that can cause hemorrhagic fevershare certain characteristics, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They all have a basic structure that consists of a core of ribonucleic acid (RNA) as the genetic material, surrounded by a fatty material. They are also all dependent on an animal or insect host for survival, and spread to humans from the infected host. (Many of these viruses can then be spread person-to-person.) Finally, all these viruses can rise to outbreaks that tend to be unpredictable, but restricted to the areas where these host species live.

Apart from these characteristics, and the fact that many of these viruses can cause hemorrhaging, the viruses don't have that much in common, Schmaljohn said. The genetics, ecology, physical structure and effects of the viruses that cause hemorrhagic fevers in different parts of the world are quite diverse, he added.

"I've long disliked the lumping of 'hemorrhagic fever viruses' with one term, because they are such different viruses, with different physical and genetic characteristics, and hemorrhage is not a consistent feature of any of them," Schmaljohn said in an email. In the current West Africa outbreak, about 18 percent of people with Ebola are developing hemorrhagic syndrome, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Despite the differences between the viruses, VHFs are often grouped together. The term VHF allows experts to talk about a nuanced subject in less complex terms, he said.

VHFs in Africa

In Africa, there are many species of animals that serve as natural reservoirs for the viruses that cause hemorrhagic fevers. For example, the strain of Ebola causing the current outbreak, Ebola Zaire, is believed to have been transferred to humans by fruit bats belonging to the Pteropodidae family, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). This bat family is also the natural reservoir for another VHF -- Marburg virus.

Marburg virus has been linked to the recent death of a man in Uganda, the Washington Post reported. Like Ebola, Marburg belongs to the Filovirus family of viruses and is spread among humans when a person comes into contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person.

Another virus found in Africa that causes hemorrhagic fever is Lassa virus, which is an Arenavirus and is native to West Africa. Unlike Ebola and Marburg, the reservoir host of Lassa is a rodent known as the multimammate rat. Whereas the Filoviruses Ebola and Marburg cannot be spread through the air, Lassa virus can be transmitted when tiny particles of rat feces or urine containing the virus become airborne, according to the Ohio Department of State Infectious Disease Control Manual (ODH-IDCM).

Lassa virus has also been known to spread when multimammate rats are caught and prepared as food for humans, according to the ODH-IDCM. Ebola and Marburg outbreaks have been linked to the consumption of infected fruit bats, which are regularly eaten by people in certain ethnic groups in West African countries such as Guinea. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

But not all VHFs are transmitted to humans by mammals. A disease known as Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever can be spread to people through tick bites, according to the WHO. Ticks infected with the Bunyavirus that causes this disease can also infect livestock, such as cattle, sheep and goats. The virus can also be carried by birds, most notably ostriches, but these animals don't show any signs of having the disease.

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever is most often transmitted to agricultural and slaughterhouse workers, as well as veterinarians, who come into contact with bodily fluids from infected animals.

VHFs around the globe

In Asia and Europe — as well as North and South America — most viral hemorrhagic fevers are spread by rodents, according to the WHO. These rodent-borne viruses known as hantaviruses all belong to the Bunyavirus family.

Asian and European hantaviruses cause an illness known as viral hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS). This means that besides hemorrhaging, these viruses can also cause kidney, or renal failure.

There are many HFRS-causing viruses in Asia and Europe, according to the CDC. These include Hantaan River virus, which is native to Korea; Seoul virus, which is native to Korea and other parts of Asia; and Puumala virus, which is native to Scandinavia and Finland but also found in Eastern Europe and Russia.

All of these viruses are spread to humans by rodents (typically mice), though the species of rodent differs depending on the region where the viruses occur. But HFRS viruses can also be "aerosolized,"or spread through airborne fragments of infected feces, urine or even dust from the rodents' nests.

Hantaviruses are spread in the same ways in North and South America, where they cause a different disease, known as hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS). This disease is characterized by a severe respiratory infection, or pneumonia, according to the CDC.

In the United States and Canada, most cases of HPS are caused by the Sin Nombre hantavirus, which was first identified in the Four Corners region of the western United States. Other hantaviruses found in North America include New York hantavirus, which is hosted by the white-footed mouse and native to the northeastern U.S., Black Creek hantavirus, which is hosted by the cotton rat and native to the southeastern U.S., and Bayou virus, which is hosted by the rice rat and native to the southeastern U.S.

There are also many hantaviruses that cause HPS in South America, according to the American Society of Microbiology. However, there have been no reports of person-to-person transmission of hantaviruses in North America and very few in South America. The Andes virus of South America has been reported as spreading from one infected human to another, but in general, person-to-person transmission of hantaviruses is considered unlikely, according to the CDC.

One of the most common of the viral hemorrhagic fevers, yellow fever, is endemic in both South America and Africa. This mosquito-borne virus infects approximately 200,000 people and kills about 30,000 people worldwide each year, according to the WHO.

Another common VHF endemic to South America, as well as parts of Mexico and the Caribbean, is dengue fever, the reservoir host for which is mosquitoes.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus