Stopping Deadly Ebola Outbreak Will Be a 'Marathon,' CDC Says

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

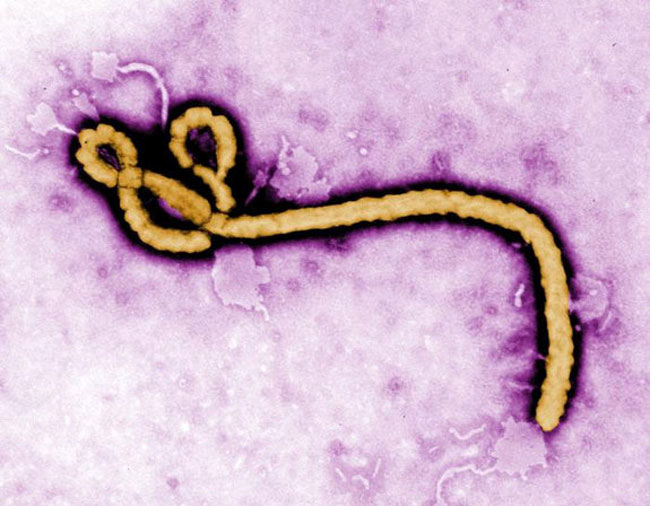

The deadly Ebola outbreak in West Africa is not showing any signs of slowing down, prompting U.S. health officials to issue more warnings for their staff in the region, encourage U.S. doctors to collect information about sick patients' travel histories and take more actions in the affected countries to bring the virus under control before it spreads to other regions.

The outbreak is the largest in history, and has now brought 672 deaths and more than 1,200 infections to Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recently, some of the health care workers responding to the outbreak, including two U.S. humanitarian workers, have become infected, as well.

"It's a rapidly changing situation, and we expect that there will be more cases in these countries in the coming weeks and months," Stephan Monroe, deputy director of CDC's National Center for Emerging & Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, told reporters today (July 28). "The response to this outbreak would be more of a marathon than a sprint." [5 Things You Should Know About Ebola]

It is always possible for the virus to reach the United States on a plane, but experts say that this does not represent a great danger. Even if the virus did arrive in that manner, it would be unlikely to spread far within the United States because of the higher standard of care in this country, experts said.

It is also unlikely that a sick passenger could spread the disease to fellow passengers, Monroe said. Ebola is generally transmitted through direct contact with blood or other bodily fluids, or contact with contaminated needles, and people are unlikely to come into contact with a fellow passenger in this way.

Nevertheless, the CDC has taken measures for preparedness in case a sick passenger brings the virus to the country, the agency said.

"We are actively working to educate American health care workers about how to isolate patients and how they can protect themselves from infection," Monroe said. The CDC encourages all health care workers to take travel histories of their patients and identify any who have traveled to West Africa within the previous three weeks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The CDC is also working on educating health care workers to recognize symptoms of Ebola, which can include fever, headache, and joint and muscle aches.

Why is it so difficult to stop this outbreak?

In order to stop any outbreak from growing, health care workers try to break the chain of transmission, that is, to identify the people who have been in contact with a patient and isolate those who may be infected.

However, despite such measures, containing this Ebola outbreak has proven difficult. Since the first cases were recognized in Guinea in February this year, the virus has spread to not only Liberia and Sierra Leone, but now also to Nigeria. That country has reported one case, a sick Liberian passenger who collapsed in the airport and later died in the hospital. The health officials in Nigeria are working to identify whether the passenger has infected anyone else.

Just between July 21 and July 23, 96 new cases and seven deaths were reported from Liberia and Sierra Leone. In Guinea, 12 new cases and five deaths were reported during the same period, after weeks of low virus activity. This shows that there are still undetected chains of transmission in the community, the World Health Organization said.

Yesterday, in a move to prevent the virus from spreading further, Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf closed all but three country borders, issued restrictions on public gatherings and quarantined affected communities, according to the Associated Press.

But major factors, including political issues and cultural trends, may be contributing to the spread of the outbreak in affected countries. People may not trust that infected relatives are safe within the health care system, or may not take preventive measures necessary to stay safe.

"There's a fair amount of distrust of the government in general, and of the messages that are being delivered," Monroe said. "We are focusing on trying to identify, in each one of the communities that are affected, the trusted sources [of information], whether it be the village elder or religious leader, somebody who we can work with to teach them first what the appropriate messages are, so that people can then accept the messages."

The Ebola outbreak is a first for West African countries. As a result, local health care workers may lack adequate training, and so may have contributed to the disease's spread by failing to wear protective clothing when treating patients, CDC officials said today. However, the American workers became infected despite having been trained for responding to Ebola, which may be a sign of higher risk of exposure in clinical settings in those countries that have less supportive measures in place. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

The CDC has deployed several teams to the affected African countries to help coordinate the response at a national level, and train other teams on how to trace people who may have had contact with infected individuals, Monroe said.

There's no cure for Ebola, so patients are treated with supportive therapy, which includes balancing their fluids, maintaining their oxygen levels and blood pressure, and treating them for any complicating infections. Although in some previous outbreaks, the mortality rate has been as high as 90 percent, it is currently around 60 percent in this outbreak, indicating efforts to treat patients early may be working, Monroe said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus