Intense El Niño May Be Developing (Photo)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

El Niño conditions seem to be developing in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, data from satellites and ocean sensors indicate.

A natural climate cycle that brings abnormally toasty temperatures to the Pacific Ocean, El Niño occurs when winds pile up warm water in the eastern part of the equatorial Pacific, triggering changes in atmospheric circulation that affects rainfall and storm patterns around the world.

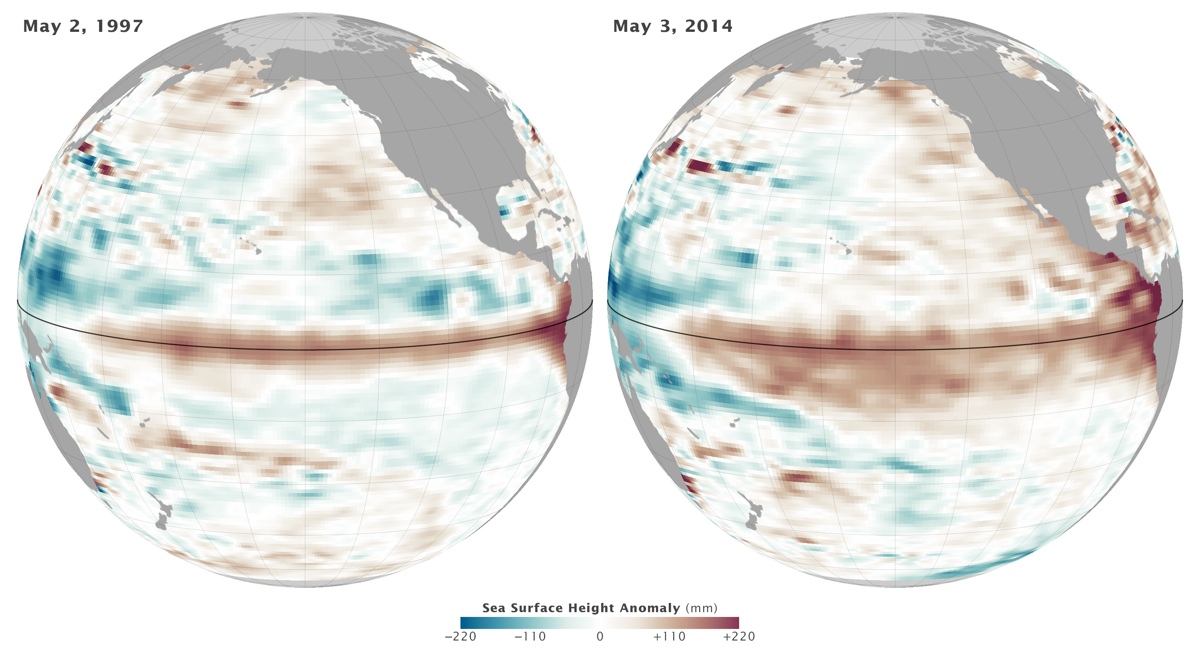

Sea-surface height can reveal if such heat is being stored in particular regions of the ocean, since water expands as it warms. Above-normal sea-surface height in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, in turn, can suggest an El Niño is developing, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. That's what is showing up right now, as satellite images taken from the Ocean Surface Topography Mission/Jason 2 satellite reveal sea-surface height, averaged over a 10-day period centered on May 3, is above normal. A similar anomaly showed up during May 1997 — which coincided with one of the strongest El Niños ever experienced. That year North America saw one of its warmest and wettest winters on record; Central and South America saw immense rainstorms and flooding; and Indonesia along with parts of Asia endured severe droughts, the Earth Observatory noted. [See 101 Stunning Images of Earth from Space]

"What we are now seeing in the tropical Pacific Ocean looks similar to conditions in early 1997," said Eric Lindstrom, oceanography program manager at NASA headquarters, in an Earth Observatory statement. "If this continues, we could be looking at a major El Niño this fall. But there are no guarantees."

A network of sensors in the Pacific Ocean reveals a deep pool of warm water shifting eastward, supporting the satellite data, according to the Earth Observatory.

Model predictions issued on May 8 by the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center forecast that the chances of an El Niño developing during the summer are more than 65 percent. "These atmospheric and oceanic conditions collectively indicate a continued evolution toward El Niño," the alert read.

This event may be just the beginning of more intense El Niños to come, according to research detailed Jan. 19 in the journal Nature Climate Change. That study suggested the most powerful El Niño events may occur every 10 years rather than every 20 years, due to rising sea-surface temperatures overall in the eastern Pacific Ocean.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus