1st sighting of 'ball lightning' in England uncovered

The monks described it as a "fiery globe threw itself down into the river."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

On June 7, 1195, a fiery spinning ball emerged from a dark cloud in an erstwhile sunny sky close to the London lodgings of the bishop of Norwich. Witnesses could never have known that the natural phenomenon that they were seeing would defy scientific explanation for more than 800 years. For what they observed has all the hallmarks of ball lightning: an atmospheric effect, the origin of which remains hotly disputed.

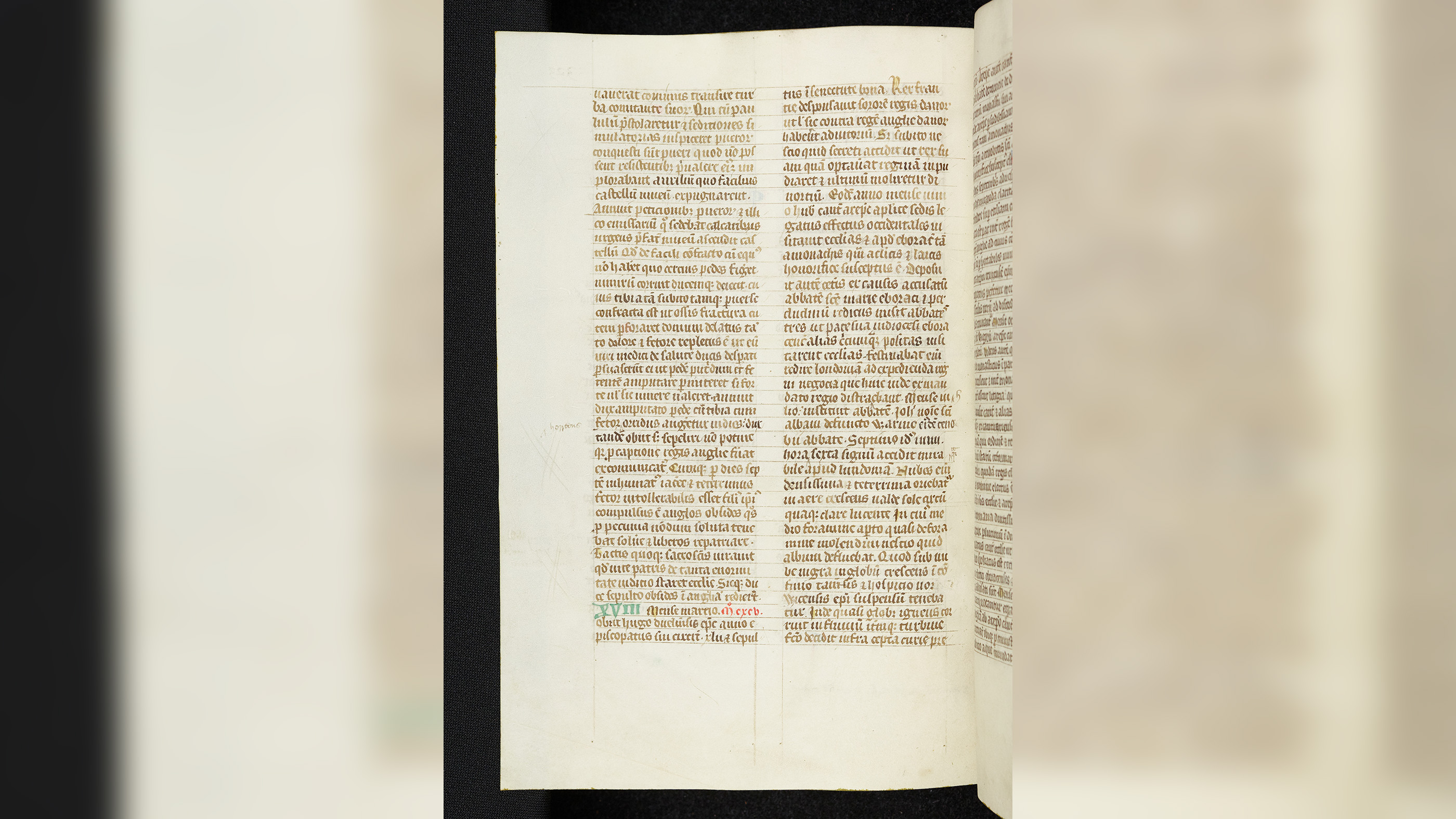

An account of this extraordinary moment survives in a monastic chronicle compiled between about 1180 and 1199 by Gervase, a monk of Christ Church Cathedral in Canterbury. It would appear that this is the first credible written record of ball lightning in England, and much more convincing than an earlier European description. Previously the earliest record of a sighting was believed to be from the 17th century.

This extensive work (nearly 600 pages in its modern edition) records historical events in England and further afield, the friends and enemies of the monastic house, and descriptions of noteworthy or unusual natural phenomena. The writing includes descriptions of solar and lunar eclipses, earthquakes and floods.

A 'marvellous sign' in the sky

We discovered the account of what appears to be ball lightning while exploring Gervase's records of natural events in his chronicle, a cornucopia of historical details giving insights into medieval culture. We dug through hundreds of pages in Latin and stumbled across this sighting, detailed in our article in Weather, the journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. Gervase's records of natural events appear within the historical narrative, often with no preamble. They were, nevertheless, clearly important enough to Gervase to be included. The ball lightning entry is sandwiched between the installation of a new abbot of St Albans and the deposition of the abbot of Thorney.

No attempt is made to explain the "marvellous sign" in the sky seen near London. The reader is left to draw their own conclusions. One abbot takes up his post, another deposed, alongside the appearance of a fiery spinning ball. In the chronicle it says:

But Gervase appears to have been an astute observer and reporter of celestial activity. For example, his seemingly fanciful description of the splitting of the image of the moon is consistent with the formation of a vertical mirage from a column of hot air from activity such as iron working or bell casting.

Gervase’s description of ball lightning is also remarkably similar to modern reports. It predates by nearly 450 years the next earliest contemporary report of ball lightning in England. This comes from an account of the storm of October 21, 1638 at Widecombe in Devon. While there is an earlier claim by Nicholas Walsh MP that in 1556 ball lightning killed his immediate family, leaving him heir to his father’s estates, the story does not appear to have been recorded until 1712 by the historian Sir Thomas Atkyns.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For a long time ball lightning was regarded with skepticism. Although it is now generally accepted as a genuine phenomenon with thousands of reported sightings, there is still no accepted scientific explanation of its origin. Highly complicated theories include the burning of silicon from vaporized soil. More recently, a suggestion has been made for light trapped inside a sphere of thin air. It is one of the oldest scientific puzzles that remains unsolved.

The moon illusion

Although rare, other long standing scientific puzzles do exist. One, that intrigued medieval natural philosophers is the "moon illusion" whereby the moon appears larger when near the horizon than when it is high in the sky. This was described by medieval thinkers, such as al-Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (born Basra, Iraq, in around AD965 and died in Cairo around AD1040) and Robert Grosseteste (1170-1253). The effect is still not totally resolved. It is certainly a psychological effect and not, as the medieval observers believed, associated with refraction.

Another is the origin of ferromagnetism, seen in the attraction between permanent magnets and iron (fridge door magnets are well known examples). Medieval authors such as John of St. Amand and Petrus Peregrinus undertook experiments on magnets that laid the groundwork for further investigation. However, it was not until 1928 that Werner Heisenberg provided a satisfactory explanation of the phenomenon in terms of quantum mechanics.

Understanding ball lightning has been hampered by an inability to reproduce the effect convincingly in the laboratory and partly because of the variations in eyewitness reports. The reported observation of ball lightning might be a first step towards providing quantitative data from which to fully explain Gervase of Canterbury’s “marvellous sign descending”.

Medieval monks such as Gervase were fascinated by the natural world and its phenomena. Centuries later, their records make stimulating reading for modern scientists as well as historians.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Giles is a Professor in High Medieval History at Durham University in England, where he focuses on the history of medieval thought and the making of medieval theology. Giles has written on Anselm of Canterbury, monastic learning in the period, especially on notions of natural phenomena and economy, and most recently on Robert Grosseteste. He is a principal investigator on a project with modern scientists as well as medieval specialists to re-edit, translate and explore Grosseteste's scientific works.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus