'RoboClam' Digging Machine As Fast as Natural Burrowers

A robot that can dig quickly and deeply into mud or wet sand could one day help lay underwater cables, dig up and detonate underwater mines, or anchor machines to the seafloor, researchers say.

The robotic digging machine, dubbed RoboClam, takes cues from the prolific burrowing abilities of the Atlantic razor clam (Ensis directus), a species of large mollusk found along the Atlantic coast of North America. By mimicking how these clams burrow through muddy soil in their coastal habitats, researchers developed a machine that could eventually aid in a variety of underwater tasks.

"When we started the project, we were looking for a means of making small, lightweight, low-power systems to move through soil," said Amos Winter, a professor of mechanical engineering at MIT. "We figured there's probably an animal that has figured out how to do this well. Razor clams stuck out because they can move through more than a kilometer of soil with the energy of an AA battery." [See video of the RoboClam]

Nature's best

Atlantic razor clams dig by opening and closing their shells quickly, Winter explained. This rapid movement sucks in water, which creates a pocket of liquid, quicksand-like material around the clam's body. That watery mix reduces drag and helps the clam move downward through the wet sand.

"The key motion is when the clam shuts its shell like a book. When this happens, it relieves the pressure from the shell pushing on the soil," Winter told Live Science. " As the clam shuts its shell, the liquidized region around the body makes it much easier to move through [that area] than the surrounding, static soil."

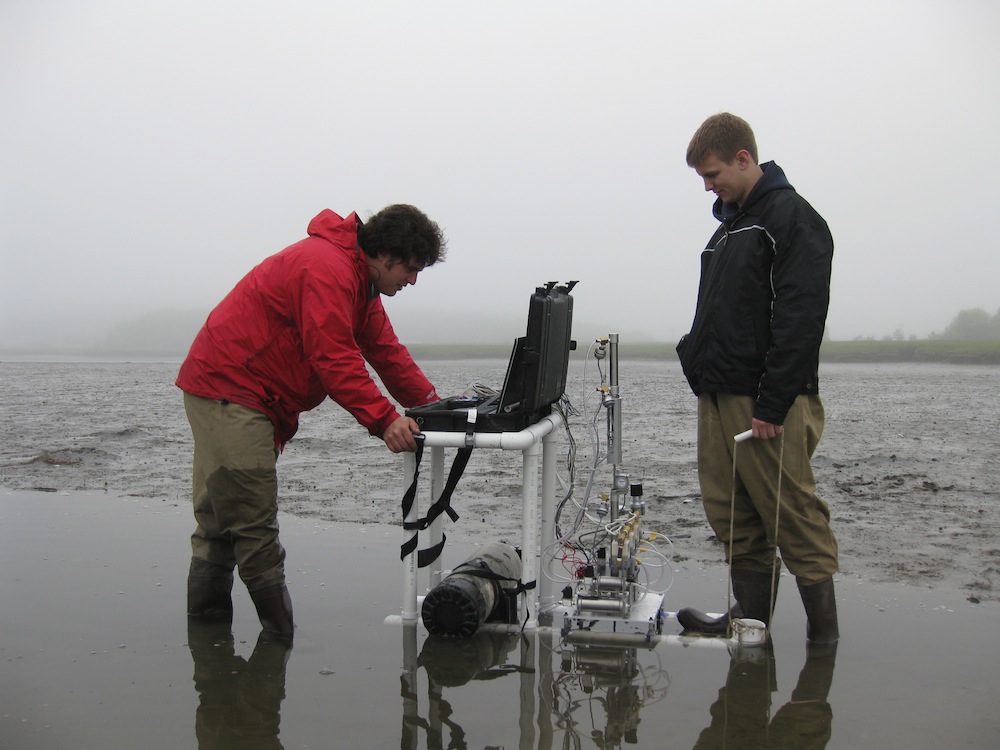

Winter and his colleagues have been experimenting with a working prototype of the RoboClam. The researchers have performed more than 300 tests of the digging machine in their lab, and in the razor clam's natural environment in the mudflats off the coast of Gloucester, Mass.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The engineers found that the RoboClam can dig at about the same speed as real razor clams, which average about 0.4 inches (1 centimeter) per second.

In trials, the RoboClam has burrowed to a maximum depth of nearly 8 inches (20 cm). The real clams can dig to a depth of about 27.5 inches (70 cm), but the current robotic prototype is limited in its reach because its motors sit above the surface of the water, Winter said.

Finding the sweet spot

Winter said he was "pleasantly surprised" that the RoboClam could work as efficiently as the creatures that inspired it. The process of fine-tuning the machine involved figuring out the perfect speed at which to open and shut the "shells" of the robotic digger, he said. If the shells moved too quickly, the water and sand did not mix into the proper fluid consistency. If the shells moved too slowly, more sand collapses in around the body of the clam than it can handle, making it difficult to dig.

"There's a sweet spot in between that maximum and minimum time," Winter said.

The researchers are still experimenting with the RoboClam, and have plans to build another prototype that could serve as a proof-of-concept model for a product that could become commercially available within two to five years, Winter said.

The researchers are already working closely with Bluefin Robotics, a Massachusetts-based company that builds and operates robotic underwater vehicles for defense, commercial and scientific purposes. The RoboClam could anchor Bluefin Robotics' vehicles when they need to remain stationary in a current, Winter said.

"Other applications include general anchoring, even in boats," he added. "We could also use the RoboClam to lay underwater cable, blow up underwater mines or set sensors in the ocean."

The research was published online today (April 8) in the journal Bioinspiration & Biomimetics.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.