Scientists burned, poked and sliced their way through new robotic skin that can 'feel everything'

New, gelatin-based material could let robots feel everything from a light poke to a deep cut.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have developed a new type of electronic "skin" that could give robots the ability to "feel" different tactile sensations like pokes, prods and temperature changes — and even the feeling of being stabbed.

The skin is made from an electrically conductive, gelatin-based material that can be molded into different shapes. When equipped with a special type of electrode, the material can detect signals from hundreds of thousands of connective pathways that correspond to different touch and pressure sensations.

The scientists said the material could be used in humanoid robots or human prosthetics where a sense of touch is vital, in addition to having broader applications in the automotive sector and in disaster relief. They published their findings June 11 in the journal Science Robotics.

Tactile sensing has emerged as the next big milestone for robotics, as scientists look to build machines that can respond to the world in a manner akin to human sensitivity.

Electronic skins typically work by converting physical information — like pressure or temperature — into electronic signals. In most cases, different types of sensors are needed for different types of sensation; for example, one to detect pressure, another to detect temperature and so on.

However, signals from these different sensors can interfere with each other, and the materials they are embedded in — traditionally soft silicones or stretchy, rubber-like materials called elastomers — are easily damaged, the scientists said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This new electronic skin uses a single type of "multi-modal" sensor that is capable of detecting different types of stimuli like touch, temperature and damage.

While it's still challenging to reliably separate and pinpoint the cause of each signal, multi-modal sensing materials are easier to fabricate and more robust, the scientists said. They're also less expensive to produce, making them suitable and cost-effective for widespread use.

That's handy

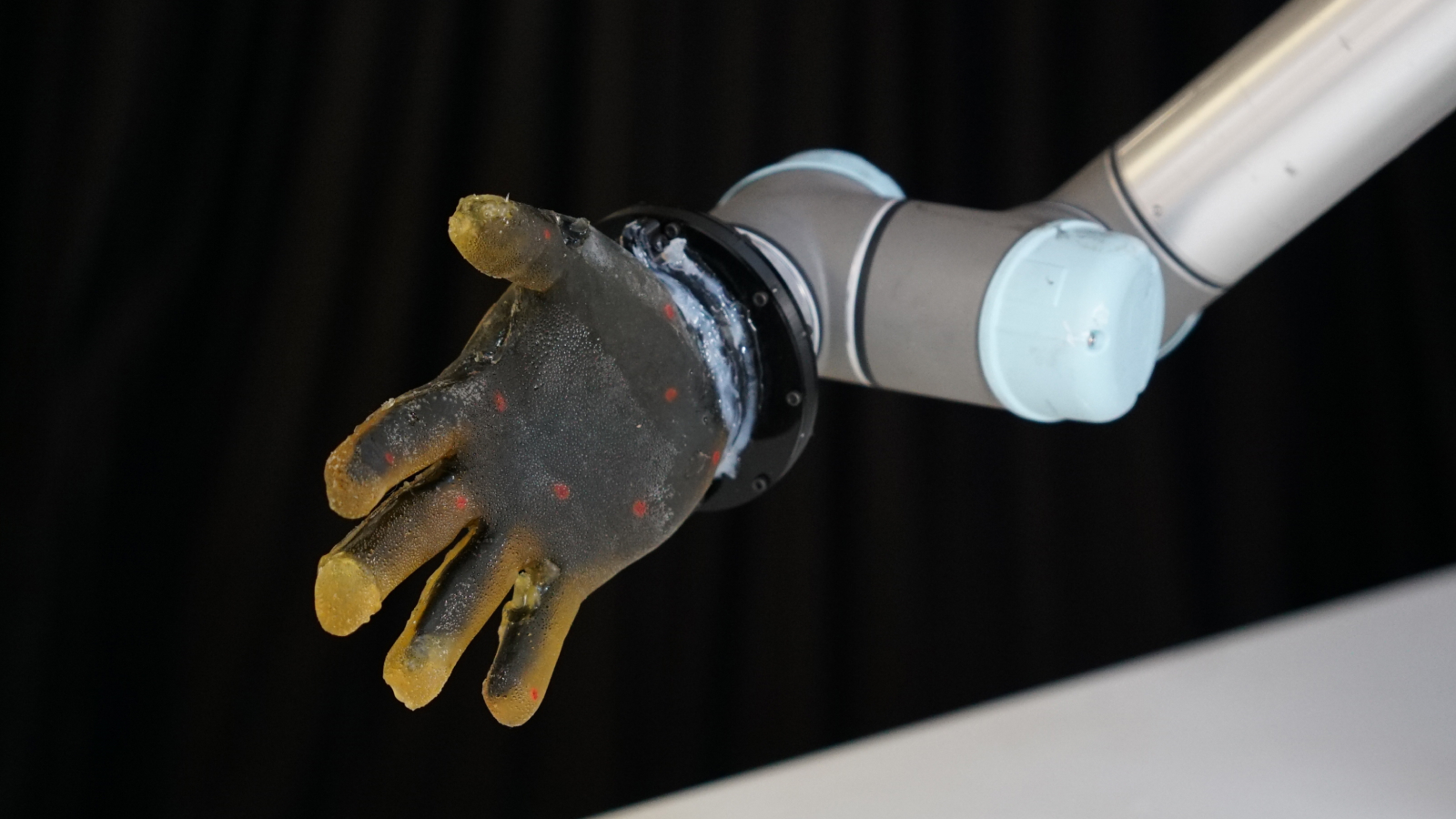

To test their synthetic flesh, the researchers melted down a soft, stretchy and electrically conductive gelatin-based hydrogel, and cast it into the shape of a human hand. They then equipped the hand with different electrode configurations to see which captured the most useful data from physical interactions, subjecting it to a series of tests to find out.

This rather brutal process involved blasting it with a heat gun, poking it with their fingers and a robotic arm, and cutting it open with a scalpel.

In total, the researchers said they collected more than 1.7 million pieces of information from the skin's 860,000-plus conductive pathways. They used data gathered from these tests to train a machine learning model that, if integrated into a robotic system, could enable it to recognize different types of touch.

"We're not quite at the level where the robotic skin is as good as human skin, but we think it’s better than anything else out there at the moment," study co-author Thomas George Thuruthel, a lecturer in robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) at University College London (UCL), said in a statement.

"Our method is flexible and easier to build than traditional sensors, and we're able to calibrate it using human touch for a range of tasks."

Owen Hughes is a freelance writer and editor specializing in data and digital technologies. Previously a senior editor at ZDNET, Owen has been writing about tech for more than a decade, during which time he has covered everything from AI, cybersecurity and supercomputers to programming languages and public sector IT. Owen is particularly interested in the intersection of technology, life and work – in his previous roles at ZDNET and TechRepublic, he wrote extensively about business leadership, digital transformation and the evolving dynamics of remote work.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus