Attila the Hun: Biography of the 'Scourge of God'

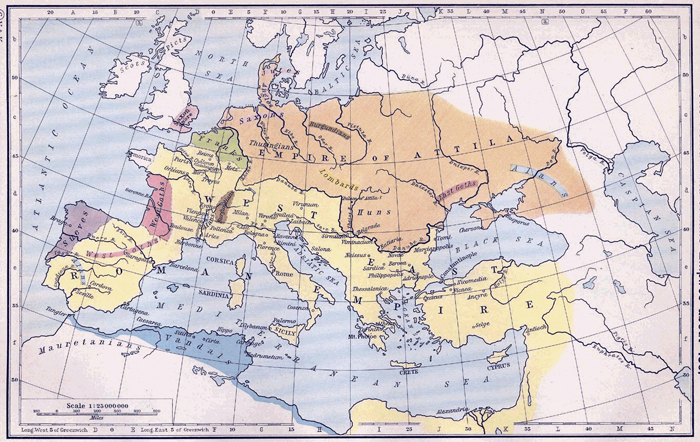

Attila was king of the Huns, a non-Christian people based on the Great Hungarian Plain in the fifth century A.D. At its height, the Hunnic Empire stretched across Central Europe. The Romans considered the Huns to be barbarians, and under Attila’s rule the Huns pillaged and destroyed many Roman cities.

His date of birth is unknown but he died in A.D. 453 on his wedding night (he practiced polygamy and had multiple wives). Whether his death was natural, or whether he was murdered by his new wife, Ildico, is still a subject of debate. By the time he died, the non-Christian Attila had become known as the “scourge of god,” and his death was cheered in what was left of the Roman Empire.

While his name has become synonymous with conquest and destruction, a careful look at historical records reveals a more complex picture. While he was responsible for destroying Roman cities he was, at one point, an ally of the western half of the Roman Empire, helping them fight other “barbarian” groups including the Burgundians and Goths. The Roman Empire had split in two by his lifetime, with the western half controlling little more than Italy and part of France.

Also while his people amassed an incredible amount of plunder, and blackmailed the eastern half of the Roman Empire out of thousands of pounds of gold, Attila himself was said to have lived relatively simply. The Roman diplomat Priscus attended a banquet with Attila and wrote that a “luxurious meal, served on silver plate, had been made ready for us and the barbarian guests, but Attila ate nothing but meat on a wooden trencher,” (translation by J.B. Bury, through Georgetown University website).

“In everything else, too, he showed himself temperate; his cup was of wood, while to the guests were given goblets of gold and silver. His dress, too, was quite simple, affecting only to be clean.” His shoes, sword and horse bridle were also unadorned.

Additionally, Attila did not believe that the ways of the Huns could be sustained forever. Priscus said that Attila was in a depressed mood at the banquet and the only person he was happy with was his youngest son, Ernas. When Priscus asked why, he was told “that prophets had forewarned Attila that his race would fall, but would be restored by this boy (Ernas).”

Rise to power

Attila was the son of Mundzuk and an unknown mother. Born into a royal family, he and his brother, Bleda, lived a relatively privileged life but still had to learn the traditional ways of the Huns, a nomadic tribe that had migrated to Europe from Central Asia in A.D. 370.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

“Together they were taught archery, how to fight with sword and lasso, and how to ride and care for a horse,” writes University of Cambridge professor Christopher Kelly in his book “Attila the Hun” (The Bodley Head, 2008). At some point, he learned how to conduct siege warfare, perhaps from Roman prisoners of war. It was a technique that would prove essential in his campaigns.

We know little about Attila’s religious beliefs; however, he did have a belief in prophecy. He was also said to have taken the discovery of a well-crafted sword by a shepherd to be a sign that he had a right to wage war.

The two brothers would start ruling jointly in A.D. 434, when their uncle, the Hun king Rua, died. Rua had been campaigning against the eastern half of the Roman Empire, trying to destroy dissident tribes that had fled Hun rule.

With his death, the two brothers focused on consolidating the Hun Empire, which stretched across much of central Europe. While the Huns were at the core of this empire, records indicate that they controlled other groups, such as those dissidents that Rua had been trying to hunt down.

The first major military action the two brothers initiated was an attack on the Burgundians, based in France, something which they did in alliance with the Western Roman Empire and their leading general, Aetius, who had obtained his position with the help of the Huns. The attack on the Burgundians was successful and in A.D. 437 they slaughtered them, wiping them out “root and branch,” wrote Prosper of Aquitane in the 450’s.

Again, in concert with Western Roman Empire, they attacked the Goths, but this time suffered a defeat at the city of Toulouse. The defeat forced the Huns to withdraw much of their forces beyond the Danube to lick their wounds. They made a peace deal with the eastern half of the Roman Empire that saw Attila and Bleda be personally paid 700 pounds of gold a year, notes Kelly.

Wars with Eastern Roman Empire

Seven hundred pounds of gold a year was a lot of money, but it apparently did not satisfy them for long. Kelly notes that in A.D. 441, when the Eastern Roman Empire sent an army to Sicily and North Africa to battle a group called the Vandals, the two brothers took advantage of the situation to launch a series of attacks across the Danube River into the Eastern Roman Empire.

They moved swiftly, their first objective being the town of Constantia. “On a crowded market day the Huns struck without warning, easily taking the town in a carefully coordinated attack on its Roman garrison,” Kelly writes.

With many of the Eastern Roman Empire’s best troops campaigning against the Vandals, the Huns could not be stopped, and Attila and Bleda rampaged through the Balkans, ignoring peace feelers offered by Emperor Theodosius II. Eventually, the emperor recalled his troops from Sicily, and Attila and Bleda called it a day, heading back beyond the Danube with a huge amount of loot.

In A.D. 445, Attila would have Bleda murdered, allowing him to become sole ruler of the Huns. Kelly notes that we don’t know how this happened.

Attila was not finished with the Eastern Roman Empire. In A.D. 446, after Theodosius II refused to pay him gold, he launched another campaign against them. Only a few months into it, an earthquake struck Constantinople, the empire’s capital, forcing its citizens to hastily rebuild its walls.

The earthquake forced the Eastern Roman Empire to do everything it could to keep the Huns away from the capital. “Soldiers and cities were repeatedly sacrificed to save Constantinople,” Kelly writes, noting that Attila never did attack the capital itself. The sixth century historian Marcellinus wrote that the Huns “attacked and pillaged forts and cities, lacerating almost all the territory surrounding the capital,” (translation from Kelly’s book).

Kelly notes that Theodosius II was forced to agree to a peace treaty in which he gave Attila 2,100 pounds of gold a year. A staggering sum but one that, Kelly notes, the eastern empire could afford. He also notes that, for Theodosius, paying Attila was cheaper than fighting against him.

Plea from a princess

A series of events caused Attila to turn his attention west, towards France. In A.D. 450, the princess Honoria, the sister of the western Roman Emperor Valentinian III, appealed to Attila for help. Kelly notes that she was an ambitious woman whom the emperor was trying to marry to an unambitious man who would keep her away from the western Roman capital at Ravenna.

She sent a servant named Hyacinthus to Attila with an offer to give him gold if he would intervene on her behalf. He also sent a ring to Attila, which he misinterpreted as being a sign that she wanted to marry him. He sent back a series of messages offering to make her one of his wives and demanding that she be made co-ruler of the Western Roman Empire.

Honoria did not want to be married to Attila and, ultimately, married the suitor that the emperor originally chose. Attila still demanded her hand in marriage but the emperor refused. Attila, in turn, threatened to kick the emperor out of his own palace and marched on France.

This time, Attila was going to get a taste of his own medicine. Valentinian III turned to Aetius, who had spent much time with the Huns, to lead the Roman troops. He also formed an alliance with the Visigoths, who hated Attila as much as the Romans did. Other “barbarian” groups in France also joined the Roman side.

The two armies clashed in northeastern France in what became known as the Battle of Catalaunian Plains (also called the Battle of Chalôns). “Attila’s plan of attack was pretty simple and that was to put the Huns themselves in the middle of the battle line and head as quickly and as directly across the field of battle and then tear apart the center of the enemy army,” said historian Victor Davis Hanson in a 2004 History Channel documentary. This happened to be where the Roman coalition line was weakest.

“They fought until they couldn’t see each other and then the battle continued into the darkness, it was one of these battles without end,” said Thomas Burns, a professor at Emory University, in the same documentary.

In the end, the Roman line held. Attila was said to be so furious at the outcome that he “screamed, yelled, he showed his masculinity, his fearlessness, and then he actually created a funeral pyre and threatened to immolate himself. So little did he value his own life and so much did his value his reputation that he would die undefeated,” said Hanson. But in the end Attila withdrew, marching his army back into central Europe.

In A.D. 452, he marched into northern Italy, forcing Valentinian III to flee to Rome. After spending time looting and destroying cities in northern Italy, Attila met Pope Leo I as an emissary. We do not know exactly happened at the meeting (Kelly notes that no eyewitness account survives) but Attila decided to pull back, taking his troops and loot back into central Europe. Kelly notes that the Eastern Roman Empire had launched an offensive beyond the Danube River into Hun territory, and Attila may have been concerned that his forces were overextended.

Attila’s death

The following year, after a great feast, Attila was found dead on his wedding night. His bride was Ildico, an apparently younger and quite beautiful woman, she was one of several wives Attila had at the same time.

Whether the bride killed Attila or whether he died of natural causes is a matter of debate. The sixth-century writer Jordanes, who used Priscus as a source, said that he died, supposedly naturally, of a hemorrhage of blood after a heavy feast. Whether this is accurate is a mystery.

“He had given himself up to excessive joy at his wedding, and as he lay on his back, heavy with wine and sleep, a rush of superfluous blood, which would ordinarily have flowed from his nose, streamed in deadly course down his throat and killed him, since it was hindered in the usual passages,” wrote Jordanes (translation by Charles Mierow, through University of Calgary website). “Thus did drunkenness put a disgraceful end to a king renowned in war.”

Attila was buried in a triple coffin of gold, silver and iron, and the people who prepared his tomb were supposedly killed so that its location would remain unknown. Indeed, to this day the tomb of Attila is still lost. It may have been looted at some point in antiquity, in which case it may never be found.

After his death his empire fell apart, his sons fighting among each other, and the western half of the Roman Empire would also fall in a few decades. Part of the prophecy that Attila dreaded, that his kingdom would collapse, had come true.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.