Glowing Millipedes Accidentally Found on Alcatraz

A plan to eliminate rats on Alcatraz, home to the famous old prison in San Francisco Bay, led to the discovery of an unfamiliar glowing creature never before seen on the island.

In early 2012, National Park Service employees placed a non-toxic dye into food for rats to eat; the dye makes the animals excrete fluorescent droppings that glow under black lights, making it easier to track the rodents. A group of workers and volunteers from the UC Davis' entomology club canvassed the island using black lights to search for evidence of rats, which threaten populations of birds on the Rock.

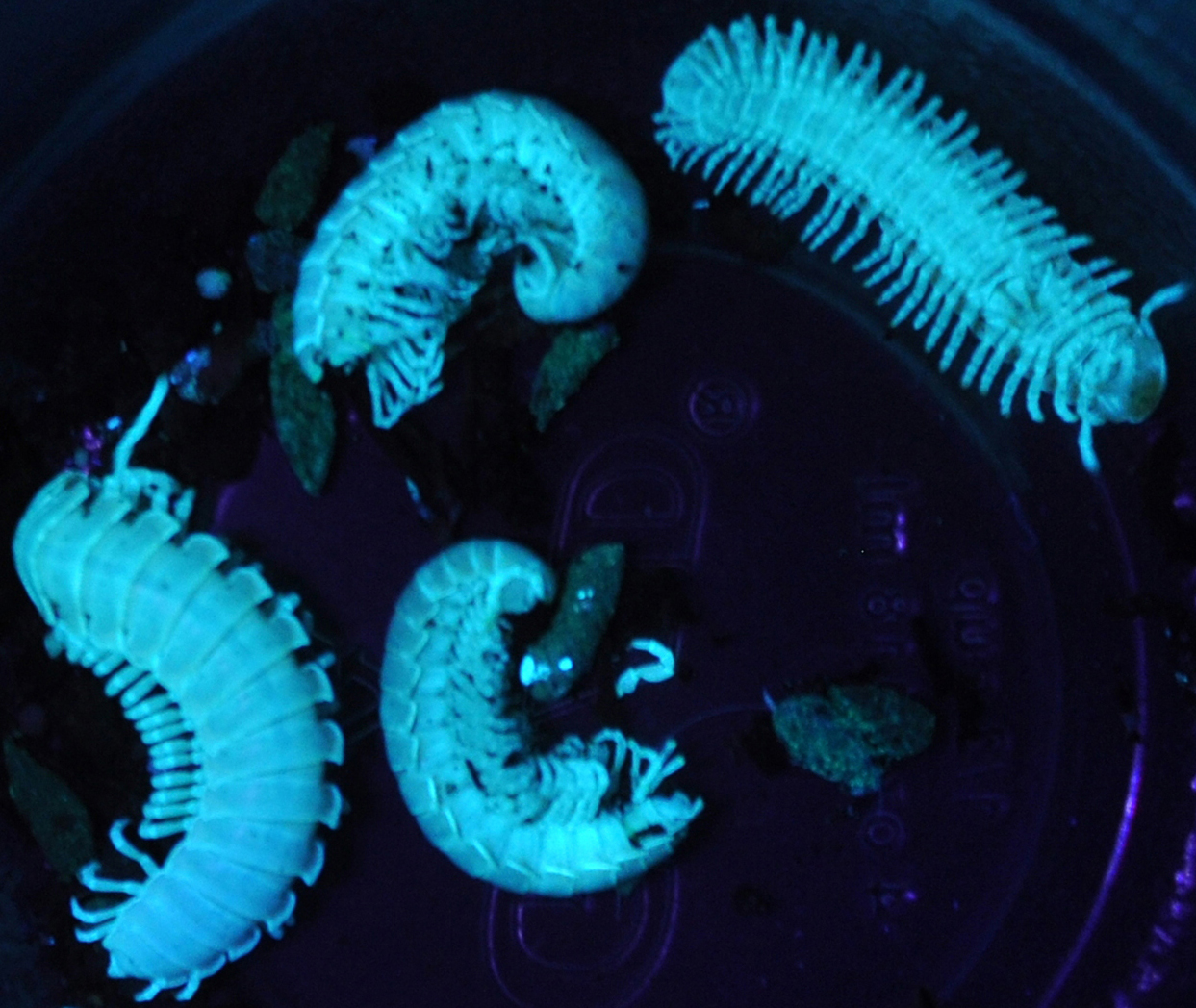

Instead of glowing rat droppings, however, the researchers found something else that glowed under their lights — and it was alive. Closer investigation revealed small, fluorescent millipedes, said UC Davis entomologist Robert Kimsey, whose student Alexander Nguyen is studying what makes the creatures glow.

(Video credit: Jenny Oh / KQED Science)

Why fluoresce?

Although other types of fluorescent millipedes live around the Bay Area, these looked slightly different to Kimsey, so he called in a millipede expert, Rowland Shelley, the curator of terrestrial invertebrates at the North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh. Shelley determined that although the strange millipedes did look slightly different from their Bay Area brethren, they fell within the same species, Xystocheir dissecta dissecta.

The species doesn't produce its own light, but instead fluoresces under the ultraviolet radiation of black lights, Kimsey said. This means that a chemical in the millipede's exoskeleton absorbs the light and then re-emits it in a slightly different wavelength, or color. It's unlikely this serves an evolutionary purpose, Kimsey said, since the insects are active at night and wouldn't normally be exposed to ultraviolet light.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Why would it fluoresce? That's the $64,000 question," he told OurAmazingPlanet. "It's nocturnal, so [fluorescing] is irrational."

Recent work has shown that many species of millipedes are fluorescent, and nobody knows exactly why, Rowland said.

Millipedes, glowing bright

But the story of glowing California millipedes gets stranger still: The Golden State is home to seven species of millipede that are bioluminescent, meaning they produce their own light, Rowland said. These species, in the same family as the Bay Area millipede, make a beautiful white light that is actually quite bright, he said. And they are all quite blind; lacking eyes, they find their way about with their antennae.

In one scientific paper from the 1960s, researchers described a group of bioluminescent millipedes in Camp Nelson (a rural area in Tulare County, Calif.) as looking like "bright stars in a dark sky on a dark night," Rowland said. [Image Gallery: The Leggiest Millipede]

On a recent trip, Rowland collected several of these glowing millipedes and brought them back to his hotel room, putting them on his bed. "I cut out the light, and once you do, the animals emit a bright, neon, white light," he said. "They go around tapping their antennae until they get to an obstacle, like when I pushed my covers up into a hump, until they find a way around. It's spectacular. It sure beats any TV program you could have on at night."

These millipedes, which aren't found anywhere else in the world, emit the light as a warning to predators that they are toxic, Rowland said. It's the nighttime equivalent of aposematic coloration — bright colors (like those of poison dart frogs) that broadcast the same message: Don't eat me.

The millipedes' bodies contain cyanide, but most are safe to handle unless you plan "to put one in [your] mouth and chew on it," Rowland said. This chemical cocktail has an unusual consequence, giving the animals an almond or cherry smell that is quite pleasant, he added. "When I collect them, I smell every one I pick up, 'cause they smell very good."

Email Douglas Main or follow him @Douglas_Main. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.