Baby Star Caught in the Act of Growing

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

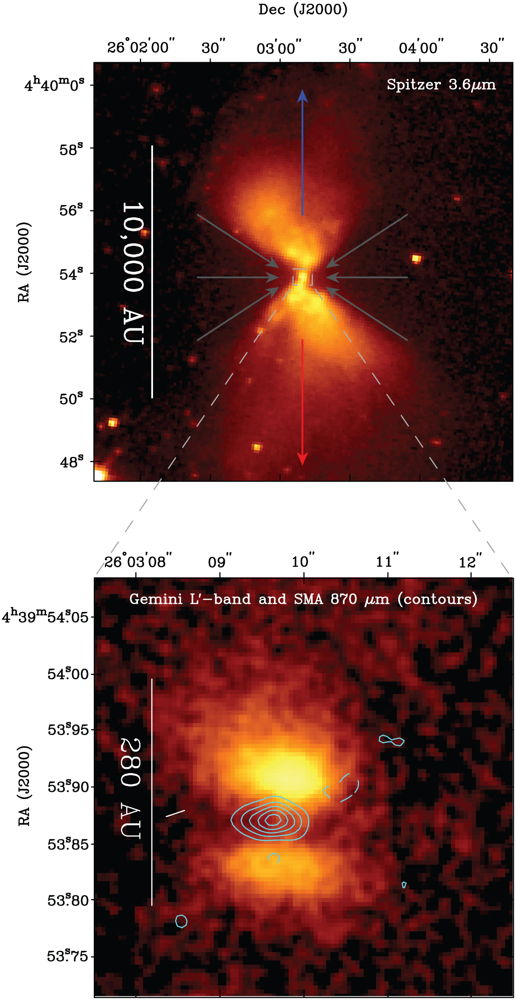

Beneath a dusty disk of creation, a baby star's mass has been measured for the first time.

The star, called L1527 IRS, is only one-fifth the mass of the sun, and is expected to keep growing as the swirling disk of matter surrounding it falls into its surface.

Astronomers estimated the star formed around the same time that Neanderthals evolved on Earth: just 300,000 years ago.

In fact, if L1527 had grown in mass just a bit more quickly in its earlier years, it could be as young as 150,000 years old. Either way, the star is among the youngest discovered in the universe, said lead researcher John Tobin.

"There's five times more material surrounding it that could be incorporated in [the star]," said Tobin, a Hubble fellow at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Virginia. "There is still a lot of room to grow, so to say."

Birth of a solar system

L1527 lies in the constellation Taurus, about 450 light-years from Earth. Its close distance makes it easier to resolve fine features in the disk. [Video: Nursery of Baby Stars Spotted By Chandra]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

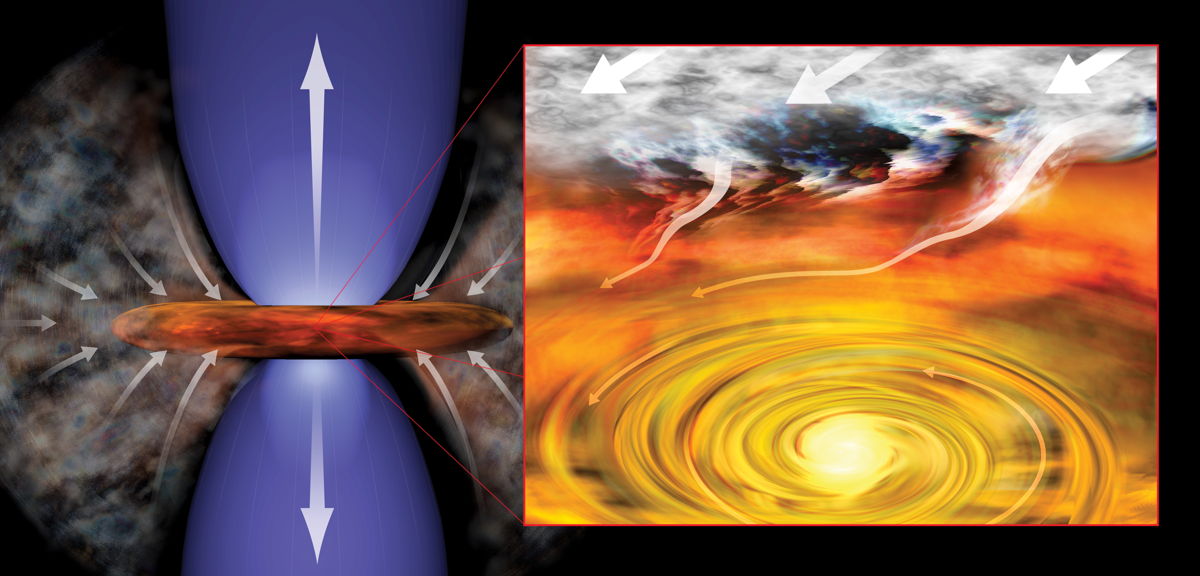

Generally, a star forms from a cloud of gas that collapses into itself. Material streams inward from the cloud and forms a protostar in the center of a disk of gas and dust.

Over millions of years, material falls on the protostar and releases quite a bit of energy. In L1527, 90 percent of its energy comes from material landing on the surface of the protostar. The remaining 10 percent comes from the star itself.

"There is a rotationally supported disk around this protostar," said Tobin, adding it's a "key element" in building planets. "It lets the material hang out long enough for the planet formation process."

But it's far too early in L1527's evolution to talk about protoplanets, he added. In the scale of stellar evolution, the star is at Stage 0. By comparison, Earth's sun is a middle-aged matron, at 4.6 billion years of age.

Mass measurements

Astronomers measured L1527's mass through simple Newtonian physics: They determined the mass by calculating the speed of the matter swirling around the protostar at a given distance.

Tobin, who has been watching this star for several years, said L1527 could serve as a useful goalpost in humans' understanding of stellar evolution.

It appears that 90 percent of young stars that are less than 1 million years old have disks of matter surrounding them. Save for the few in multiple-star systems who see their disks blown away, it appears disk formation is a universal process in a young star's life.

Tobin was granted telescope time at the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, which is a new radio telescope array that reveals a universe not seen in visible and infrared light.

"We want to get a more detailed view of the structure of the rotating disk," he said, adding, "We're also trying to look at more young protostars to find more disks like this. You can get a big picture view of everything that’s going on."

The research will be published in the Dec. 6 issue of the journal Nature and includes collaborations with astronomers in the United States, Germany and Mexico.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus