Ocean on Jupiter's Moon Europa Likely Deep Underground

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

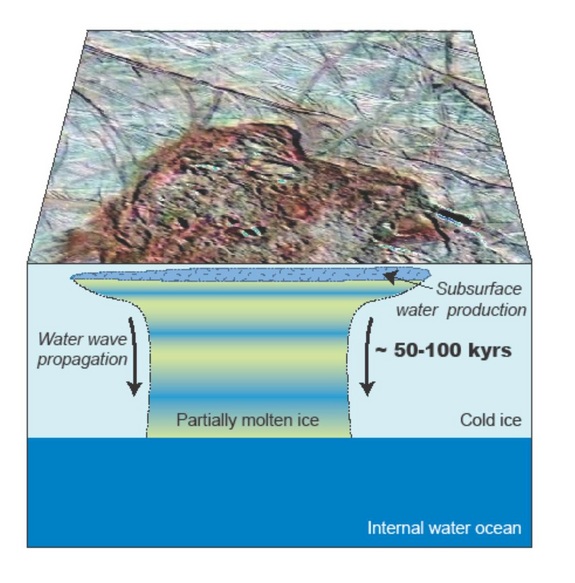

Missions hoping to explore the huge subsurface ocean thought to exist on Jupiter's moon Europa may have to dig deep — really deep.

Water stays in a liquid state near Europa's surface for just a few tens of thousands of years or so, new research suggests. That's a blink of an eye in geological terms, since our solar system is more than 4.5 billion years old.

"A global water ocean may be present, but relatively deep below the surface — around 25 to 50 kilometers," Klára Kalousová, of France's University of Nantes and Charles University in Prague, said in a statement today (Sept 24).

"There could be areas of liquid water at much shallower depths, say around 5 kilometers, but these would only exist for a few tens of thousands of years before migrating downwards," Kalousová added. [Gallery: Photos of Europa]

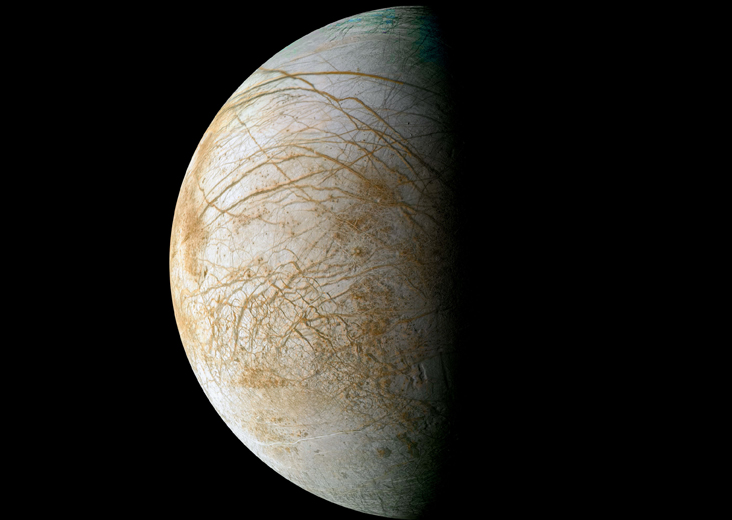

Many researchers think Europa, which is about 1,900 miles (3,100 km) wide, harbors an enormous global ocean beneath its shell of ice. While Europa's surface is frigid, heat generated in the moon's interior by Jupiter's gravitational pull keeps this ocean — which may be 60 miles (100 km) deep — from freezing solid.

Here on Earth, life thrives wherever liquid water is found. So Europa is an intriguing target for future missions seeking signs of life elsewhere in the solar system.

But scientists don't know how difficult it would be for a future Europa probe to access the moon's ocean, because they're not sure how deep beneath the crust it lies. Some researchers have speculated that pockets of liquid water may persist just a few miles below the surface, but the new study throws cold water on that prospect.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kalousová mathematically modeled how mixtures of liquid water and solid ice behave in a variety of conditions. She found that differences in density and viscosity, along with several other factors, probably cause water near Europa's surface to migrate downward rapidly through partially melted ice to meet up with the larger ocean.

Europa isn't the only moon in the solar system that may have an underground ocean. Fellow Jovian moons Callisto and Ganymede might have one, for example, and so might Saturn's icy satellite Enceladus.

The new study could help scientists better understand these frigid worlds, as well as Saturn's huge moon Titan, which has a hydrocarbon-based weather system, Kalousová said.

"As well as helping us to better understand Europa’s water cycle, this research could provide insight into icy moons that are geologically active, such as Enceladus, and worlds that have cycles connecting the interior with a surface atmosphere, such as Titan," she said.

Kalousová will present the research at the European Planetary Science Congress in Madrid on Tuesday (Sept. 25).

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus