Astronomers Find Cosmic 'Dragonfish' Packed with Supermassive Stars

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers have spotted the most jam-packed cluster of young supermassive stars ever seen in the Milky Way galaxy, including hundreds of the most massive types of stars that are dozens of times heavier than our sun.

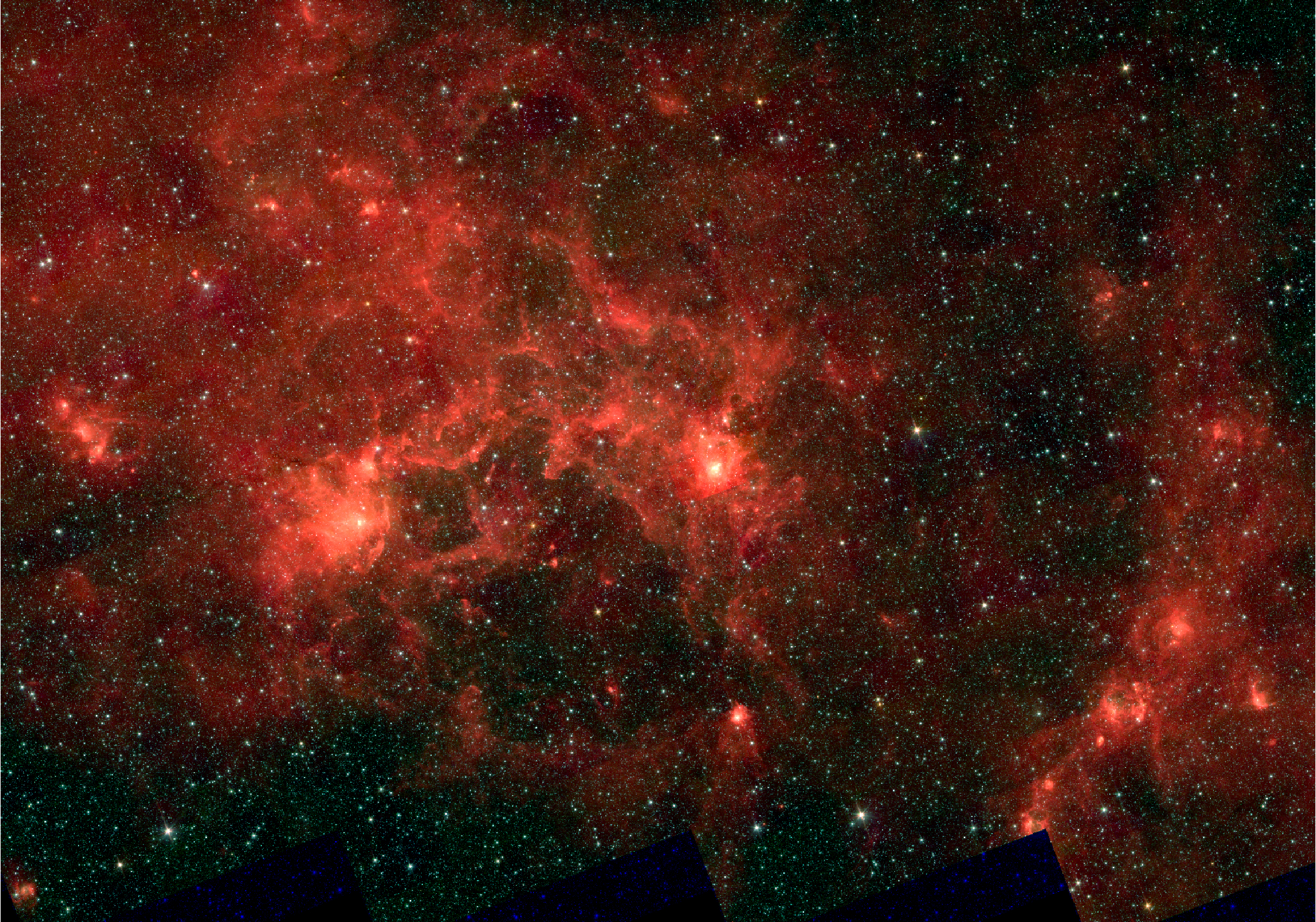

The light from these hefty newborn stars is heating the surrounding clouds of gas and dust, punching out a hollow shell into space that measures roughly 100 light-years wide, the researchers said.

"By studying these supermassive stars and the shell surrounding them, we hope to learn more about how energy is transmitted in such extreme environments," Mubdi Rahman, a doctoral student at the University of Toronto in Canada, said in a statement.

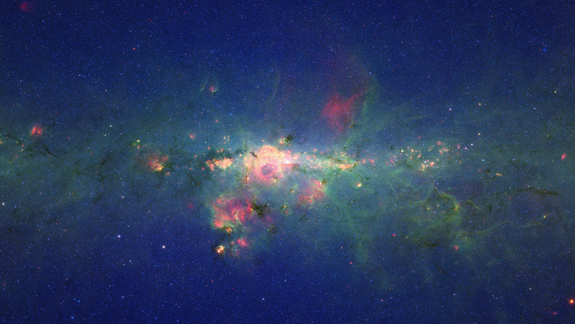

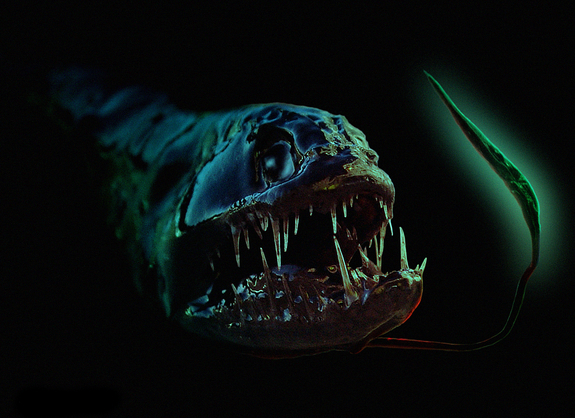

Rahman, who led the study with his supervising professors, Dae-Sik Moon and Christopher Matzner, suggested the name "Dragonfish" to describe the cosmic scene, because the infrared image of the shell of gas resembles the undersea creature's dark, gaping mouth and teeth, with bright spots corresponding to two eyes and a fin to the right, the researchers said.

Star clusters

Large nurseries chock full of massive stars have previously been detected in other galaxies, but these were so distant that the stars often blurred together in telescope images, the astronomers said.

"This time, the massive stars are right here in our galaxy, and we can even count them individually," Rahman said. [Strangest Things in Space]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But there are still challenges: The star cluster is located about 30,000 light-years away — nearly halfway across the Milky Way — and dust obstructs the line of sight from Earth. This has made it difficult to glean precise measurements of these stars or determine what type they are, Rahman said.

"These stars are incredibly bright, yet, they're very hard to see," he explained. This is because as light from the young stars travels toward Earth, it is largely absorbed by intervening dust in the galaxy, making these stellar giants appear as dim as smaller, nearby stars. In fact, the fainter stars in the cluster appear so dim they cannot be seen.

Rahman and his colleagues were able to study a few dozen stars using the New Technology Telescope at the European Southern Observatory's La Silla Observatory in Chile. They gathered extensive data on the light emitted by these stars and were able to confirm that at least a dozen stars in the cluster were the most massive kind, with some possibly weighing 100 times more than the sun.

Gas shell in space

Using the infrared eyes on NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, the researchers were able to take an image of the gas shell being blown away from the newborn stars.

And while the shell may be expansive, it certainly is not empty, Rahman said. For each of the few hundred supermassive stars the researchers found, there are thousands of hidden average stars that are more similar to the sun. Other bright patches in the shell could represent gas that has been compressed enough to generate more young stars.

"There may be newer stars already forming in the eyes of the Dragonfish," Rahman said.

The gas presently in the shell is the remainder of the gas that gave birth to the massive stars, but the astronomers have also detected a young star that appears to be wandering free of the cluster's mass and gravity.

"We've found a rebel in the group, a runaway star escaping from the group at high speed," Rahman said. "We think the group is no longer tied together by gravity: however, how the association will fly apart is something we still don't understand well."

Details of the study's findings will be published in the Dec. 20 issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus