Searchers of Ringed Alien Planets Put Faith in Kepler Probe

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

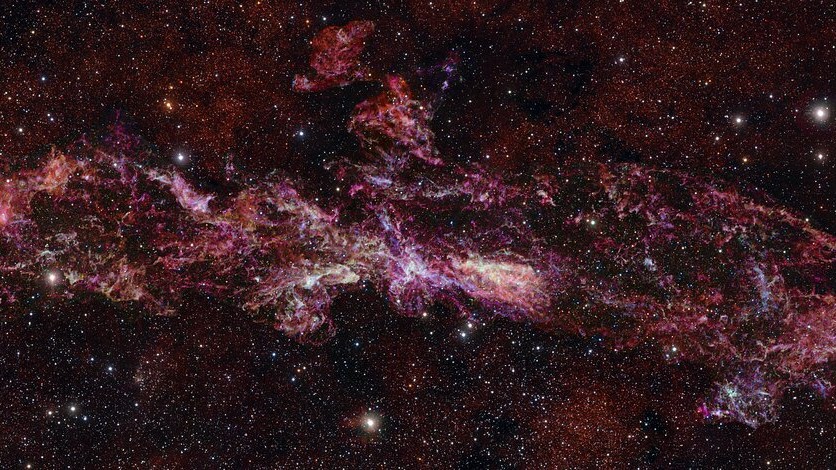

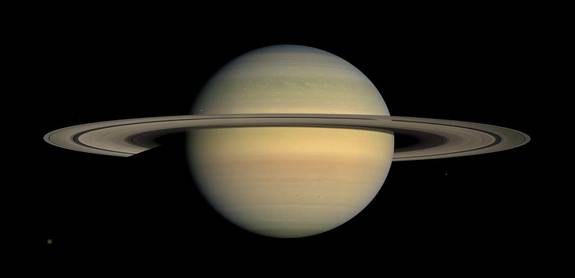

Saturn-like worlds may abound throughout the universe, and NASA's planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft has the ability to find them, astronomers say.

Rings surround the gas giants in our solar system, but scientists have yet to find any on similar alien planets. The precise instruments on the Kepler spacecraft could change that.

"The ideal areas to try and look for rings are the regions Kepler is sensitive to," Hilke Schlichting, of the University of California, Los Angeles, explained.

Schlichting and Philip Chang of the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics examined the types of rings that could form around large gas planets orbiting near their stars. [Photos: The Rings and Moons of Saturn]

Before Kepler scientists announced the spacecraft's discovery of over 1,200 potential alien worlds in February, gas giants with small orbits dominated Kepler's planetary findings.

Rocky rings

Such planets would likely be surrounded by rings made of rock rather than ice, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As with Saturn, the particles in these rings would range from micron size to tens of meters wide. Schlichting told SPACE.com they would resemble the bands around our own solar system's most notably ringed planet.

Of course, they might not appear exactly the same. Rings form around the equator of a planet, so if the planet is tilted in respect to Earth, the rings may be tipped on edge, or appear to surround the planet like a circular frame.

Some rings even may have a kink to them. That is, a portion of the ring near the planet would move out smoothly from the halo, then sharply bend. Such a warped ring might occur if the tilt of the planet changed over time, which could reveal details about the planet's interior.

But figuring out details like warps would come later, the researchers said.

"First we have to find the rings, then we can worry about signatures" in them, Schlichting said.

Searching for rings

Finding the rings alone could reveal details about how large gas giants – which Schlichting calls 'warm Saturns' but actually run the gamut from Neptune- to Jupiter-size – wound up so close to their suns.

According to current formation models, gas giants can form only far from the heat of their parent star. The question is whether they then migrate smoothly inward or scatter inward at random.

"If we could detect several of these systems, they could tell us how the bodies got there."

If rings formed with their planet, they would likely be icy. As they moved closer to the star, they would evaporate. If the planet moved in slowly, it would be more likely to pick up rocks in its rings than a rapidly moving, erratic body would.

Because the rings form around the equator, they can also reveal the orbital axis of a planet in relation to its parent star, or its obliquity. This also could help determine how these hot giants formed.

Schlichting is confident that the Kepler spacecraft will reveal a number of ringed alien planets.

"Given that Kepler has found 1,000 extrasolar planet candidates, the chances that we would find rings in this data are very high."

It's simply a question of sifting through the existing data, Schlichting said.

"I think it will be within this year," she said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus