Ancient Furry Featherweight Mammal Discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

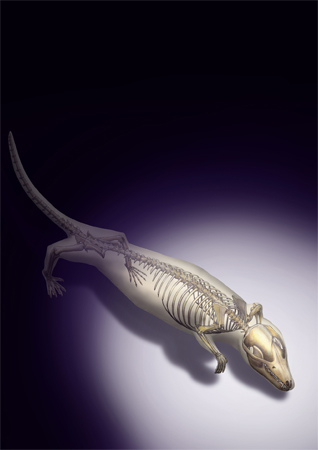

Fossil remains have revealed a new svelte, squirrel-like mammal that scurried around in the wee hours of the night snagging insects and worms about 125 million years ago.

Paleontologists unearthed the remains in the Yan Mountains in what is now the Hebei Province in China. A reconstruction of what the animal looked like in life shows a five-inch-long furry critter weighing less than an ounce, with short limbs and claws ideal for digging and traipsing along the ground.?

The animal's lengthy physique, supported by 26 thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, is unlike most living and extinct terrestrial mammals which tend to bemuch stouter (humans are much larger and yet have just 33 vertebrae in their spines). The scientists attribute the high number of vertebrae to genetic mutations that occurred during the deep Mesozoic time.

The furry featherweight [image], dubbed Yanoconodon allini, belongs to a primitive Mesozoic mammal group known as triconodonts, defined by the three cusps lined up on its molar teeth.

Besides adding to the picture of what the region's ecosystem was like in ancient times, the fossil of this nocturnal mammal [image] sheds light on the evolution of the modern ear structure.

Found in relatively pristine condition, the animal's middle-ear structure was still attached to the lower jaw bone by so-called Meckel's cartilage. The position of the ear bones provides a snapshot of a critical, and until now, missing, intermediate point in the evolution of the modern mammalian ear.

"This new fossil offers a rare insight in the evolutionary origin of the mammalian ear structure," said Zhe-Xi Luo of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. He headed up the study of the mammal, detailed in the March 15 issue of the journal Nature.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mammals top other vertebrates when it comes to the sophistication of their hearing. Three tiny bones that make up the middle ear are responsible for mammals' stellar hearing ability. While scientists have known the delicate bones evolved from precursor jaw bones in our reptilian relatives, the question of how the jaw hinge got separated from the jaw over evolutionary time and made its way into the middle ear of the mammals has plagued scientists for more than a century.

"Now we have a definitive piece of evidence, in a beautifully preserved fossil split on two rock slabs," said Luo. "Yanoconodon clearly shows an intermediate condition in the evolutionary process of how modern mammals acquired their middle ear structure."

- Top 10 Missing Links

- Why are Ears Shaped So Strangely?

- Beyond the Controversy: How Evolution Works

- Ten Amazing Animal Abilities

- Images: Dinosaur Fossils

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus