10 Amazing Things You Didn't Know about Animals

10 Amazing Things You Didn't Know about Animals

Myths and mysteries make the fascinating, but even odd creatures ought to be understood. We explore a few recent findings, common misconceptions and amazing adaptations.

Learn the truth about elephant minds, how one creature finds 29 hours in a day, and the real reason crocodiles bellies are full of stones.

Editor’s Note: This article, originally published in 2007, was updated in March 2016 to reflect recent research and new information.

Parrot Talk More than Just Squawking

Parrot speech is commonly regarded as the brainless squawking of a feathered voice recorder. But studies over the past 30 years continually show that parrots engage in much more than mere mimicry. Parrots are capable of logical leaps and can solve certain linguistic processing tasks as deftly as 4-6 year-old children. Parrots appear to grasp concepts like "same" and "different," "bigger" and "smaller", "none" and numbers. They understand zero Perhaps most interestingly, they can combine labels and phrases in novel ways. A January 2007 study in Language Sciences suggests using patterns of parrot speech learning to develop artificial speech skills in robots.

Elephants Do Forget, but They're Not Dumb

Elephants have the largest brain — nearly 11 pounds on average — of any mammal that ever walked the earth. Do they use that gray matter to the fullest? Intelligence is hard to quantify in humans or animals, but the encephalization quotient (EQ), a ratio of an animal's observed brain size to the expected brain size given the animal's mass, correlates well with an ability to navigate novel challenges and obstacles. The average elephant EQ is 1.88. (Humans range from 7.33 to 7.69, chimpanzees average 2.45, pigs 0.27.) Intelligence and memory are thought to go hand in hand, suggesting that elephant memories, while not infallible, are quite good.

Giraffes Compensate for Height with Unique Blood Flow

The stately giraffe, whose head sits some 16 feet up atop an unlikely pedestal, adapted his long neck to compete for foliage with other grazers. The long necks of giraffes date back to ancestors that lived 16 million years ago, according to a study reported October 7, 2015 in the journal Royal Society Open Science. While the advantage of reach is obvious, some difficulties arise at such a height. The heart must pump twice as hard as a cow's to get blood up to the brain, and a complex blood vessel system is needed to ensure that blood doesn't rush to the head when bent over. Six feet below the heart, the skin of the legs must then be extremely tight to prevent blood from pooling at the hooves.

Many Fish Swap Sex Organs

With so many land creatures to wonder at, it's easy to forget that some of the weirdest activities take place deep in the ocean. The strange practice of hermaphroditism is more common among species of fish than within any other group of vertebrates. Some fish change sex in response to hormonal cycle or environmental changes. Others simultaneously possess both male and female sex organs. Scrawny male molly fish flaunt their bisexuality to improve their mating odds, according to research reported in the journal Biology Letters.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Baby Chicks and Brotherhood

It's a mistake to think of evolution as producing selfish animals concerned only with their own survival. Altruism abounds in cases where a helping hand will encourage the survival of genetic material similar to one's own. Baby chicks practice this "kin selection" by making a special chirp while feeding. This call announces the food find to nearby chicks, who are probably close relations and so share many of the chick's genes. The key to natural selection isn't survival of the fittest animal. It's survival of the fittest genetic material, and so brotherly behavior that favors close relations will thrive. Chimps are also known to be selfless on occasion.

Mole-Rats aren't Blind

With their puny eyes and underground lifestyle, African mole-rats have long been considered the Mr. Magoos of rodents, detecting little light and, it has been suggested, using their eyes more for sensing changes in air currents than for actual vision. But findings of the past few years have shown that African mole-rats have a keen, if limited, sense of sight. And they don't like what they see, according to a report in the November 2006 Animal Behaviour. Light may suggest that a predator has broken into a tunnel, which could explain why subterranean diggers developed sight in the first place. [Perspective: Why We Love Naked Mole Rats]

For Beavers, Days Get Longer in Winter

Beavers become near shut-ins during winter, living off of previously stored food or the deposits of fat in their distinctive tails. A beaver conserves energy by avoiding the cold outdoors, opting instead to remain in dark lodgings inside their pile of wood and mud. As a result these rodents, which normally emerge at sunset and turn in at sunrise, have no light cues to entrain their sleep cycle. The beaver's biological sense of time shifts, and she develops a "free running circadian rhythm" of 29-hour days. Such a shift in human circadian rhythm would mess with a human's ability to sleep and function.

Birds Use Landmarks to Navigate Long Journeys

We humans have detailed maps, GPS navigation systems and even Siri to guide us wherever we'd like to go. Birds, smart as they are, haven't learned to use any of this technology. Yet pigeons can fly thousands of miles to find the same roosting spot with no navigational difficulties. Some species of birds, like the Arctic tern, make a 25,000 mile round-trip journey every year. Many species use built-in ferromagnets to detect their orientation with respect to the Earth's magnetic field. A November 2006 study published in Animal Behaviour suggests that pigeons also use familiar landmarks on the ground below to help find their way home. Still, much about bird navigation remains a mystery, according to this 2014 this perspective piece by University of Oxford researcher Tim Guilford.

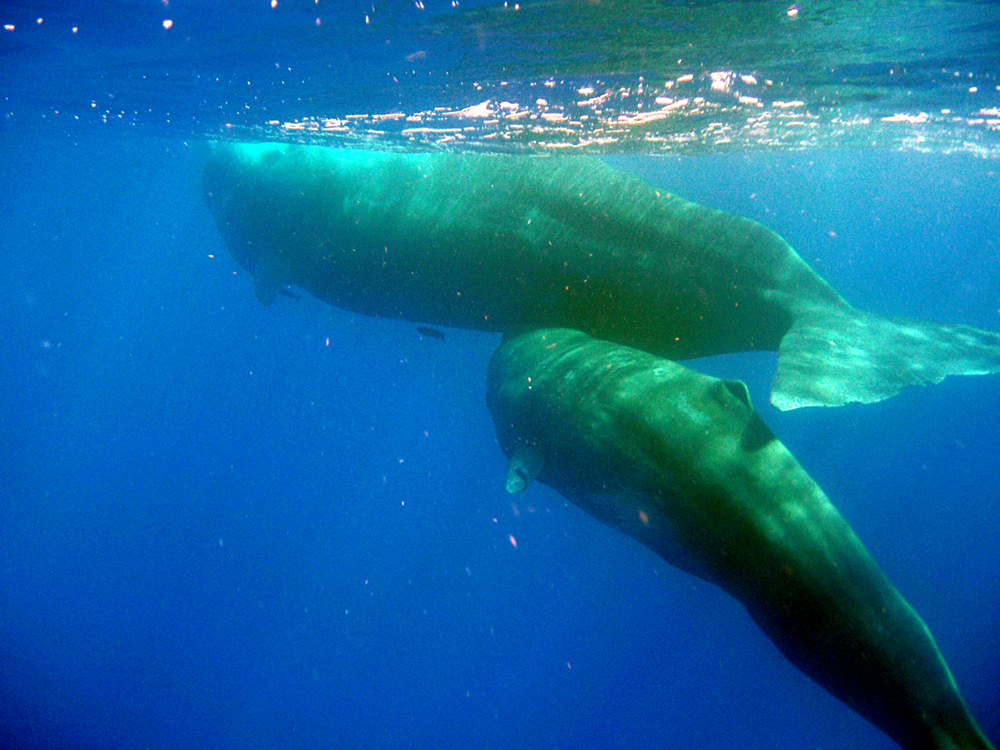

Whale Milk Not On Low-Fat Diets

Nursing a newborn is no small feat for the whale, whose calf emerges, after 10 to 12 months in the womb, about a third the mother's length (that's a 30-foot baby for the Blue whale). The mother squirts milk into the newborn's mouth using muscles around the mammary gland while the baby holds tight to a nipple (yes, whales have them). At nearly 50 percent fat, whale milk has around 10 times the fat content of human milk, which helps calves achieve some serious growth spurts — as much as 200 pounds per day. It should be no surprise that whale moms then quickly teach their young where to eat on their own.

Crocodiles Swallow Stones for Swimming

The stomach of a crocodile is a rocky place to be, for more than one reason. To begin with, a croc's digestive system encounters everything from turtles, fish and birds to giraffes, buffalo, lions and even (when defending territory) other crocodiles. In addition to that bellyful-o'-ecosystem, rocks show up too. The reptiles swallow large stones that stay permanently in their bellies. It's been suggested these are used for ballast in diving.

Since you made it all the way, here are some bonus crocodile facts: The largest croc ever found was 20.24 feet (6.17m) long. These reptiles are cold-blooded, so in winter they hibernate. A croc can lay up to 60 eggs at a time!