How the Giraffe Got Its Iconic Neck

The age-old question of how the giraffe got its long neck may now be at least partly answered: Long necks were present in giraffe ancestors that lived at least 16 million years ago, a new study finds.

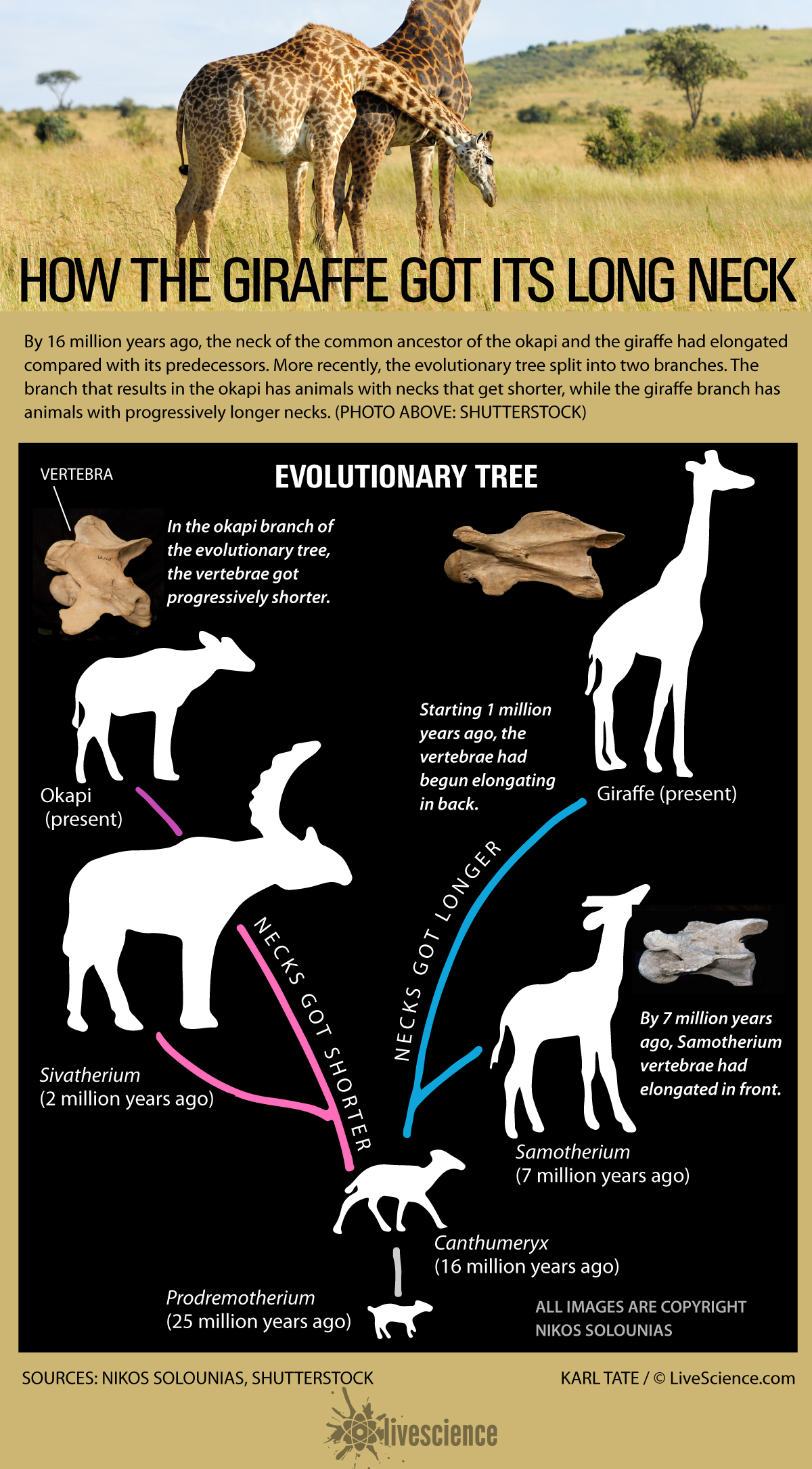

In the study, researchers examined the cervical (neck) vertebrae from 71 animals, including modern giraffes, their relatives and their ancient ancestors. They found that two species — Prodremotherium elongatum, which lived 25 million years ago and was potentially an ancestor of modern giraffes, and Canthumeryx sirtensis, which was a giraffe ancestor that lived 16 million years ago — both had elongated necks.

These ancient animals were different enough from their modern counterparts that they are not classified as part of the giraffe family. Therefore, the fossils indicate that "cervical lengthening precedes Giraffidae," the researchers wrote in the study, using the scientific name for the giraffe family. [In Photos: See Cute Pics of Baby Giraffes]

In other words, the long neck came before the giraffe.

As the researchers put it, writing in their report published in the Oct. 7 issue of the journal Royal Society Open Science, "the most distinguishing and popular attribute" of giraffes is "apparently not a defining feature of the family."

The study is one of the first to rigorously compare the necks of giraffes with those of their relatives and ancestors to see how they changed over time, the researchers said.

"We wanted to figure out how the giraffe got its long neck because we know that its ancestors had a shorter neck," said the study's senior researcher, Nikos Solounias, a professor of anatomy at the New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study included animals from 11 species, including nine extinct species and two living species — the giraffe and the okapi, a giraffe relative native to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The researchers focused on the third cervical vertebra of each species, and compared the modern animals' vertebrae with those of their ancestors. Giraffes, like humans, have seven cervical vertebrae, but the giraffe's vertebrae are large, measuring up to 10 inches (25.4 centimeters) long.

After Canthumeryx, the ancestor that lived 16 million years ago, the family tree split into two branches. The researchers found that on one branch, four species had evolved shorter necks over time. The okapi, with its short neck, is on this side of the family tree.

Before the new study, researchers thought the okapi was "more primitive" than modern giraffes, because it had a shorter neck, Solounias told Live Science. But the new findings showed the okapi is descended from animals that had longer necks than it does.

Long-neck inheritance

On the other branch of the family tree, the species evolved longer necks over time. A key point came about 7 million years ago, when the front side of each vertebra began getting longer, contributing to the neck lengthening in species such as Samotherium major, which is a member of the modern giraffe family.

Then, about 1 million years ago, in another species, the back part of each vertebra lengthened, which also contributed to the modern giraffe's neck.

In other words, the fossil trail shows that the neck "elongated disproportionally," Solounias said. "In the beginning you had an anterior [front] elongation, and then later, you had a posterior [back] elongation."

The researchers verified their work using a mathematical equation that showed how the neck vertebrae would be expected to morph over time. The equation showed that the Samotherium vertebra (which had already lengthened in the front) would need to elongate at its back end, just as the researchers had predicted based on the fossils.

Now that researchers know that the giraffe's neck is at least 16 million years in the making, they can continue trying to figure out what drove the evolution toward longer necks. One idea is that it helped the animals graze on leaves high above the heads of other herbivores.

Another is that the longer necks gave males an advantage in mating, said Melinda Danowitz, a medical student at the NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine, who also worked on the study. In today's giraffes, males fight by swinging their heads and necks against each other, and females tend to mate with males that win these fights, she said.

There is fierce debate on both sides, but both ideas may explain why giraffes benefit from having such long necks, Danowitz said.

The new study is an important one, said Donald Prothero, a research associate in vertebrate paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, who was not involved with the new study.

"[It] shows the mechanism by which giraffes lengthened their necks," he told Live Science in an email. "In the past we only had fossils of short-necked giraffes (like the living okapi and most extinct giraffes) and long-necked giraffes.

"This study describes new fossils, which have necks intermediate in length between the giraffe and the okapi," he said. "It includes not only a description of new fossils, but also a detailed analysis of the development of the neck vertebrae and their functional anatomy."

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus