Study: Global Warming Near Critical Level

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Global temperatures are dangerously close to the highest ever estimated to have occurred in the past million years, scientists reported today.

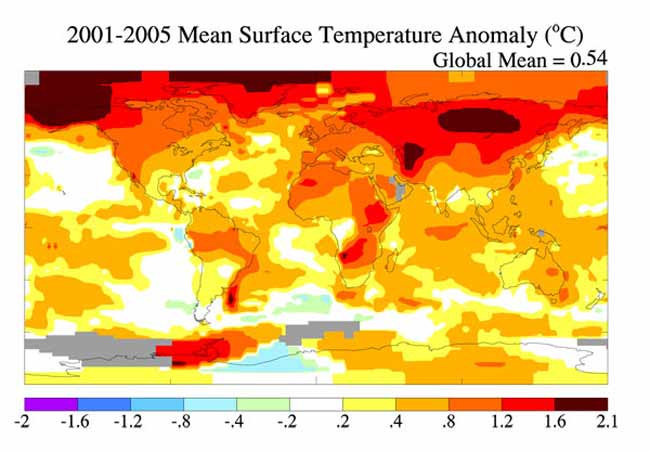

In a study that analyzed temperatures around the globe, researchers found that Earth has been warming rapidly, nearly 0.36 degrees Fahrenheit (0.2 degrees Celsius) in the last 30 years [chart].

"The average surface temperature is 15, maybe 16 degrees Celsius (60 degrees Fahrenheit)," said Alan Robock, a meteorologist and climate researcher from Rutgers University who was not involved with the study.

If global temperatures go up another 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius), it would be equal to the maximum temperature of the past million years.

"This evidence implies that we are getting close to dangerous levels of human-made (anthropogenic) pollution," said study leader James Hansen of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

'A different planet...'

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, human-made greenhouse gases are responsible for most of the warming of the last 50 years. The gasses, released by burning of fossil fuels and land clearing among other factors, trap heat in the atmosphere and warm Earth's surface.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Further global warming of 1.8 degree Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) defines a critical level, Hanson said.

Robock agrees that temperatures are getting up there.

"It's certainly the warmest it's been in the last couple of thousand years," Robock said. "I don't have access to the data about the last million years but it's probably right. I just haven't looked at it in detail."

"During the warmest interglacial periods the Earth was reasonably similar to today. But if further global warming reaches 2 or 3 degrees Celsius, we will likely see changes that make Earth a different planet than the one we know," he said. "The last time it was that warm was in the middle Pliocene, about three million years ago, when sea level was estimated to have been about 25 meters [80 feet] higher than today."

The study also notes that global warming is greatest at higher latitudes near the poles. This is because when the Earth warms, snow and ice melt, uncovering darker land and ocean surfaces. Instead of the once-white surface that reflected solar rays back into space, the darker surfaces now absorb more energy from the sun.

Mass migration

Although warming is most noticeable at the poles, higher latitudes are still among the coolest spots around. For animals and plants that can only survive within certain cool temperature ranges these are the only places to go as their current homes become intolerably warm.

In a 2003 study, scientists showed that 1,700 plant and animal species migrated toward the poles at about 4 miles per decade in the last 50 years.

That migration rate is not fast enough to keep up with the current rate of movement of a given temperature zone, which has reached about 25 miles (40 kilometers) per decade in the period 1975 to 2005, Hanson and co-authors write in the current issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Rapid movement of climatic zones is going to be another stress on wildlife," Hansen said. "It adds to the stress of habitat loss due to human developments. If we do not slow down the rate of global warming, many species are likely to become extinct. In effect we are pushing them off the planet."

- Global Warming Takes a Break

- Warmer Winters Cause Remarkable Loss of Arctic Sea Ice

- Arctic Summer Could be Ice-Free by 2105

- Images: Glaciers Before and After

- All About Global Warming

Hot Topic

What makes Earth habitable? This LiveScience original video explores the science of global warming and explains how, for now, conditions here are just right.

The Controversy

- Global Warming or Just Hot Air? A Dozen Different Views

- Global Warming Differences Resolved

- Conflicting Claims on Global Warming and Why It's All Moot

- Baffled Scientists Say Less Sunlight Reaching Earth

- Scientists Clueless over Sun's Effect on Earth

- Greenhouse Gas Hits Record High

- Key Argument for Global Warming Critics Evaporates

The Effects

- Seas Rise

- More Wildfires

- Deserts to Grow

- Greenland Melts

- Mountains Grow

- Ground Collapses

- Glaciers Disappear

- Allergies Get Worse

- Summer Gets Longer

- Animal DNA Changing

- Animals Change Behavior

- Rivers Melt Sooner in Spring

- Increased Plant Production

- Hurricanes Get Stronger

- Some Trees Benefit

- Lakes Disappear

The Possibilities

- More Rain but Less Water

- Ice-Free Arctic Summers

- Overwhelmed Storm Drains

- Worst Mass Extinction Ever

- A Chilled Planet

Strange Solutions

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus