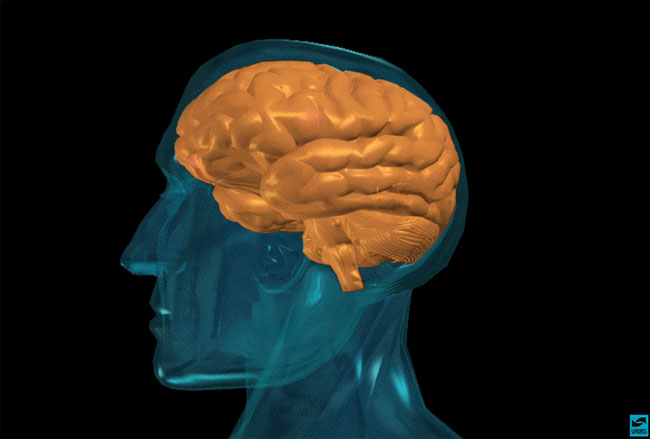

Do Brains Shrink As We Age?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

As we get older, our brains get smaller, or at least that's what many scientists believe. But a new study contradicts this assumption, concluding that when older brains are "healthy" there is little brain deterioration, and that only when people experience cognitive decline do their brains show significant signs of shrinking.

The results suggest that many previous studies may have overestimated how much our brains shrink as we age, possibly because they failed to exclude people who were starting to develop brain diseases, such as dementia, that would lead to brain decay, or atrophy.

"The main issue is that maybe healthy people do not have as much atrophy as we always thought they had," said Saartje Burgmans, the lead author of the study and a PhD candidate at Maastricht University in the Netherlands.

Burgmans and her colleagues wondered what would happen if they were able to screen out all of the people with so-called "preclinical" cognitive diseases. Using information collected for Holland's Maastricht Aging Study, the researchers analyzed data from 65 "healthy" individuals who did not show signs of dementia, Parkinson's disease or stroke and who were monitored for a period of nine years. Participants were on average 69 years old at the study's start.

Every three years, participants completed neuropsychological tests, which were designed to assess their cognition. They also underwent a brain MRI scan.

From the test results, the researchers divided the participants into two groups: a "healthy" group of 35 people, who showed no loss of mental abilities, and another group of 30 people who showed substantial cognitive decline, but did not have dementia.

Then, they analyzed the brain scans, looking at the size of seven regions associated with cognition. In the healthy group, age did not have a significant effect on brain size. In the other group, there was a large effect in all seven brain areas — older participants had significantly smaller brain areas than younger ones.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What we found is that when you exclude all those people [who] are suspicious for preclinical disease, and you just look at the healthy people who don't have any suspicious cognitive decline, then you see that there is a very small age effect in this group," said Burgmans.

The researchers caution that their findings are only preliminary, and that they need to be confirmed in a larger group of people. Also, future studies should include brain scans of people over time, and not just one brain scan, as was the case for this study.

But their results demonstrate that it is important for scientists studying the aging brain to assess the cognition of their participants over a number of years, the researchers say.

The study was published in the September issue of the journal Neuropsychology.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus