In Tough Times, Nature Favors Female Brains

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have known that male and female mammals respond differently to starvation, with male cells tending to conserve protein while female calls lean toward fat conservation.

But what happens in the brain, where cells need a complex set of nutrients to fire properly? A new study of rodents, thought to be a good analogue to humans, offers hints.

The upshot: "When it comes to keeping brains alive, it seems nature has deemed that females are more valuable then males," the researcher said in a statement yesterday.

Past studies looking at the effect of starvation on animal bodies have been done mostly by looking at nutrient-rich tissues like muscles, fat deposits, and the liver. Robert Clark and colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center grew neurons taken from male and female rats or mice in lab dishes, then subjected them to nutrient starvation over 72 hours.

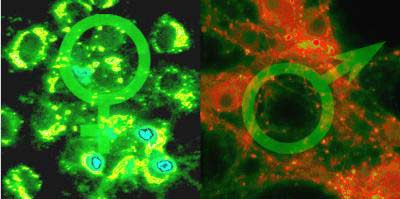

After 24 hours, the male neurons experienced significantly more cell dysfunction. A key indicator called cell respiration decreased by more than 70 percent in male cells compared to 50 percent in female cells. Visually, male neurons showed more signs of autophagy, whereby a cell breaks down its own less vital components to use as a fuel source, while female neurons created more lipid droplets to store fat reserves.

Male neurons basically eat themselves from the inside, the scientists conclude.

The nutrient deprivation "produced cell death more profoundly in neurons from males versus females," Clark's team writes in the Jan. 23 issue of Journal of Biological Chemistry. "Thus, during starvation, neurons from males more readily undergo autophagy and die, whereas neurons from females mobilize fatty acids, accumulate triglycerides, form lipid droplets, and survive longer."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The work is part of a broader effort to understand how the bodies and brains of various animals, including humans, use nutrients, and what happens as we age. In perhaps one of the most unexpected reactions to starvation, rattlesnakes draw on their own cells for nutrients and actually grow their bodies longer when food is scarce.

In recent years, several studies have shown that one surefire way to increase life expectancy among humans is a severely restricted calorie diet, one that of course stops short of starvation, however. A study last month in the journal Neuron found that slow, chronic starvation of the brain as we age — caused when it does not get enough glucose due to cardiovascular disease restricting blood flow — can trigger a biochemical process that causes some forms of Alzheimer's disease.

As with other cell culture studies, the result of the new research may not be truly indicative of what happens in living animals during starvation, the scientists note.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

- Men and Women Really Do Think Differently

- Brain News, Information and Images

- Brain Food: How to Eat Smart

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus