Whales Found to Speak in Dialects

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Some whale species sing in different dialects depending on where they're from, a new study shows.

Blue whales off the Pacific Northwest sound different than blue whales in the western Pacific Ocean, and these sound different than those living off Antarctica.

And they all sound different than the blue whales living near Chile.

"The whales in the eastern Pacific have a very low-pitched pulsed sounds, followed by a tone," said David Mellinger of Oregon State University. "Other populations use different combinations of pulses, tones, and pitches."

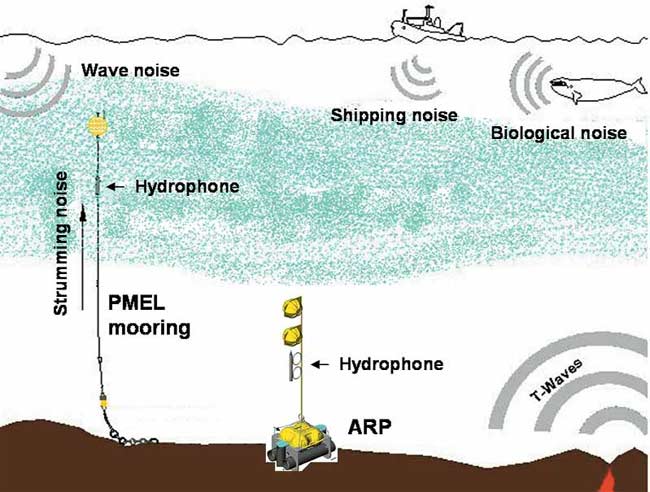

Using newly developed underwater microphones called autonomous hydrophones, Mellinger and his colleagues recorded the cacophonous symphony of whale clicks, pulses, and calls throughout the Pacific Ocean.

The hydrophones—which can be deployed independently rather than the Navy's Sound Surveillance System—were developed to listen for earthquakes. But researchers soon realized that they were picking up the sounds of right whales from 25 miles away, and even farther if the water is shallow and the terrain is even.

Researchers also heard the calls of critically endangered North Pacific right whales and sperm whales in the Gulf of Alaska. Many of the sperm whales were detected during the winter—nearly twice as many as in the summer—indicating a surprisingly active "off-season" population that scientists had never known.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There are a handful of records of people spotting sperm whales in the region—and they're all in the summer," Mellinger said. "The Gulf of Alaska is not a place you want to be in the winter. But apparently, sperm whales don't mind."

Researchers don't know why whales around the world sound differently.

"The difference is really striking, but we don't know if it is tied to genetics, or some other reason," Mellinger said. "We don't know if they are part of a common ‘language' that different populations of whales use to communicate with each other, or if they come from a confused juvenile who hasn't completely learned the complexities of communicating."

The researchers plan to deploy three more hydrophones near a series of long-duration NOAA moorings in the Bering Sea this spring. They plan to analyze possible connections between the appearance of whales and current conditions.

The results from this and other acoustic surveys could help produce more sophisticated surveys that could allow scientists to provide data in near-real time.

The research is detailed in the January issue of the journal BioScience.

- How to Reduce Accidental Whale Deaths

- Ship Noise Drowns Out Whale Talk, a Threat to Mating

- Deep-Diving Whales Suffer From Bends

- Scientists Inseminate a Whale

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus