Early Whales Had Legs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The first whales once swam the seas by wiggling large hind feet, research now suggests.

These new findings shed light on the mysterious shift these leviathans made away from land.

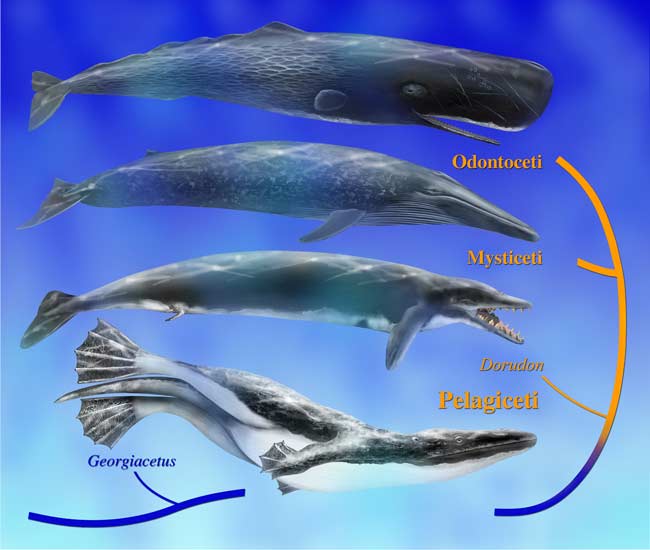

The ancestors of whales once strode on land on four legs, just as other mammals do. Over time, as they evolved to dwell in water, their front legs became flippers while they lost their back legs and hips, although modern whales all still retain traces of pelvises, and occasionally throwbacks are born with vestiges of hind limbs.

A great deal of mystery surrounds how the anatomy of the first whales changed to propel them through the water. A key piece of that puzzle would be the discovery of when exactly the wide flukes on their powerful tails arose.

"The origin of flukes is one of the last steps in the transition from land to sea," explained vertebrate paleontologist Mark Uhen of the Alabama Museum of Natural History in Tuscaloosa.

To shed light on this mystery, Uhen analyzed new fossils that amateur bone hunters discovered exposed along riverbanks in Alabama and Mississippi. These bones once belonged to the ancient whale Georgiacetus, which swam along the Gulf Coast of North America roughly 40 million years ago, back when Florida was mostly submerged underwater. This creature reached some 12 feet in length and likely used its sharp teeth to dine on squid and fish.

The first whales known to possess flukes are close relatives of Georgiacetus that date back to 38 million years ago. But while only about 2 million years separate Georgiacetus from these other whales, Uhen now finds that Georgiacetus apparently did not possess flukes. The new 2-inch-long tail vertebra he analyzed — one of some 20 tail vertebrae the ancient whale had — is not flattened as the vertebrae near whales flukes are.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Instead, Uhen suggests that Georgiacetus wiggled large back feet like paddles in order to swim. Past research showed this ancient whale had large hips, which suggested it also had large hind legs. Oddly, scientists had also found that its pelvis was not attached to its spine. This meant its hind legs could not paddle in the water or support the whale's body weight on land, leaving it a puzzle as to what they were for until now.

"The idea we are now helping confirm is that this ancient whale wiggled its hips to swim, moving its feet like hydrofoils or paddles. So it swam rather like a modern whale, which undulates its body up and down," Uhen told LiveScience.

The scientists detailed their findings in the latest issue of the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- The Gay Gray Whale

- Useless Limbs Vestigal Organs

- World's Biggest Beasts

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus