This Bizarre Ancient Sea Monster Looked Like the Millennium Falcon

A long time ago, in a galaxy not at all far away, a carnivore with an uncanny resemblance to the Millennium Falcon from "Star Wars" scuttled through the seas.

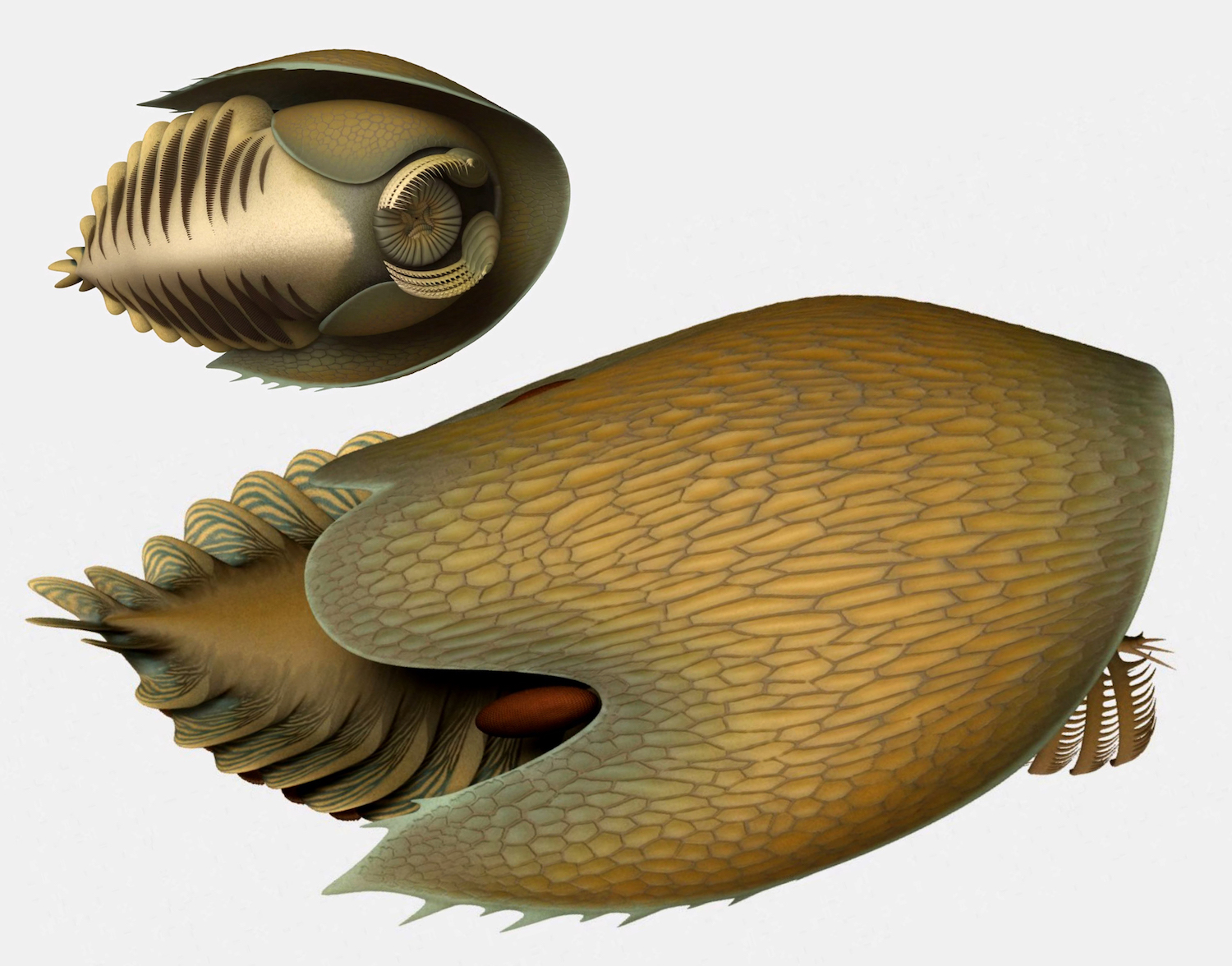

This Cambrian period creature wasn't just fearsome; it was also well protected, as a huge shell, known as a carapace, covered the animal's back. The tips of this shell jutted out in sharp spikes. There was probably a downside, however, to this enormous, spaceship-shaped shell.

"The body is a bit ridiculous," study co-researcher Jean-Bernard Caron, curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada. "It has this humongous head with this humongous shell and these tiny, little [swimming flaps underneath]. So, there is something that looks dysfunctional in its ability to swim very efficiently." [See illustrations and fossils of this Millennium Falcon-shaped creature]

Researchers named the 506-million-year-old beast Cambroraster falcatus. The genus name is a nod to the Cambrian period and the creature's rake-like appendages (in Latin, "rastrum" means "rake"). The species name celebrates the Millennium Falcon. (When it comes to the "Star Wars" movie franchise, "who is not a fan?" Caron asked Live Science.)

Caron and his colleagues first came across C. falcatus fossils in 2012, during a dig in the Burgess Shale deposit in the Canadian Rockies, a spot famous for its trove of well-preserved Cambrian fossils. But the fossils were piecemeal. It wasn't until 2018 that the researchers hit the jackpot, a spot packed with these "spaceship animals," as the paleontologists nicknamed the creatures. The large assemblage of fossils indicated that this particular C. falcatus group was molting en masse, the researchers said.

"They were not just isolated predators," Caron said. "They lived in large groups and they molted together."

This now-extinct C. falcatus was a type of primitive arthropod known as a radiodont, a distant relative to modern-day spiders, crustaceans and insects. Of the 140 individuals paleontologists uncovered, it appears that most adult C. falcatus were about the size of a person's hand, although the largest one measured nearly 1 foot (30 centimeters) long.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Its size would have been even more impressive at the time it was alive, as most animals living during the Cambrian period were smaller than your little finger," study lead researcher Joe Moysiuk, a doctoral student in ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto, who is based at the Royal Ontario Museum, said in a statement.

In fact, C. falcatus is related to Anomalocaris, a gigantic, carnivorous, shrimp-like creature that was "the top predator living in the seas at that time, but it seems to have been feeding in a radically different way," Moysiuk said.

The Millennium Falcon look-alike probably used its rake-like claws to sift through the seafloor's sediment, Caron and Moysiuk said. It's also possible it used its impressive shell to plough through the muck to discover tasty meals. Prey such as small fish were then stuffed into the creature's circular, tooth-lined mouth, the researchers said.

The creature is a "pretty amazing puzzle," said Jakob Vinther, a paleobiologist at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, who was not involved with the study. However, he wondered if C. falcatus truly raked its claws through the ocean floor.

Usually, animals that do this have short and blunt claws that won't break as they comb through the muck. In contrast, the claws of C. falcatus are long and slender, so perhaps this predator was a filter feeder that waved its claws through the water column, trapping small, shrimp-like critters, Vinther said.

Even so, he tipped his hat to the researchers. "It's a fantastic fossil, and I think they have made some excellent analyses of the animal," Vinther told Live Science.

The study will be published online today (July 31) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

- Image Gallery: Bizarre Cambrian Creature

- Photos: Ancient Shrimp-Like Critter Was Tiny But Fierce

- Photos: Ancient Marine Critter Had 50 Legs, 2 Large Claws

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus