Ancient Monster Shrimp Was a Real Softie

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A gigantic carnivorous shrimp that roamed the seas 500 million years ago may not have been so vicious a killer after all, according to a new study. The research suggests that instead of crunching its prey, it gummed its food.

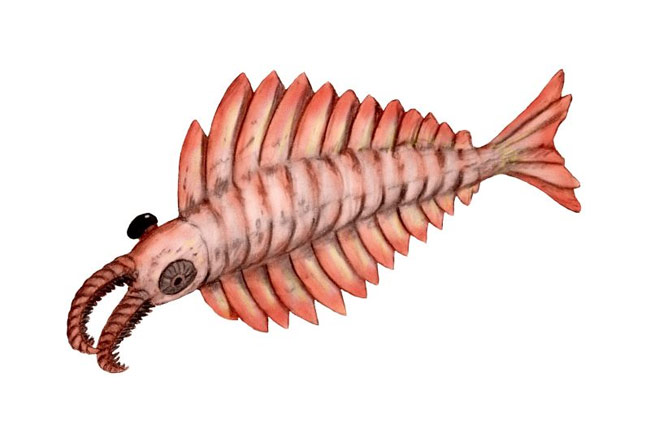

The Anomalocaris was a shrimplike creature that grew up to 3 feet (1 meter) long. Based on its tentacle-surrounded maw, researchers envisioned the creature as a shell-chomping monster. [Image of Anomalocaris]

"The popular opinion is that it's a giant predator cruising the sea... eating trilobites and other hapless prey," paleontologist James "Whitey" Hagadorn of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science told LiveScience. "The research I presented yesterday (Nov. 1) doesn't dispell the notion that it was a predator, but it does dispell the notion that it was eating trilobites."

Hagadorn presented the results at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America in Denver.

Soft mouthparts

Hagadorn was measuring the mouthparts of 400 fossils of Anomalocaris when he noticed that the creature seemed to be soft-mouthed. He saw no evidence of chipped teeth or broken mouthparts as would be expected in a shell-chewing predator. And many of the fossils were warped in ways that suggested that Anomalocaris' mouth, a whorl surrounded by whisker-like appendages, was bendable.

These suspicions prompted Hagadorn and his colleagues to develop a three-dimensional model of the creature's mouth. The model allowed them to test how much force the creature could generate with a bite. They also measured modern shelled creatures, from shrimp to lobsters, to use as analogues to ancient trilobite shells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The model showed that Anomalocaris couldn't have regularly chowed down on trilobites. It would have been able to swallow very small trilobites whole or gum down on recently molted trilobites, the ancient equivalent of soft-shell crab. But typical trilobites were out of the question.

"For the vast majority of trilobites, like 95 percent, the mouth of Anomalocaris would have broken before it broke the trilobite," Hagadorn said.

Wear and tear

As additional evidence, Hagadorn points to the fact that crushed-up shells of any kind are conspicuosly absent from fossil Anomalocaris guts. A lack of evidence can't be used to support a theory, he said, but in context, it's suspicious.

"It'd be like finding a crime scence with no blood in it, and no victim, and no murder weapon," he said. "And no evidence of a crime."

Instead of eating shelled animals, Anomalocaris may have combed through the mud for soft-bodied worms, Hagadorn said. Or it may have used its tentacled mouth to filter for plankton in the water, much like many whales do today.

"These things wouldn't show up in its stomach, because they're all soft-bodied," Hagadorn said.

- Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures

- Extremophiles: World's Weirdest Life

- Amazing Animal Abilities

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus