'Patchwork' Early Human Fossils Suggest Intermixing

Fossils unearthed in China appeared to be strange patchworks of extinct and modern human lineages, with the large brains of modern humans; the low, broad skulls of earlier humans; and the inner ears of Neanderthals, a new study reported.

These new fossils suggest that far-flung groups of ancient humans were more genetically linked across Eurasia than often previously thought, researchers in the new study said.

"I don't like to think of these fossils as those of hybrids," said study co-author Erik Trinkaus, an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis. "Hybridization implies that all of these groups were separate and discrete, only occasionally interacting. What these fossils show is that these groups were basically not separate. The idea that there were separate lineages in different parts of the world is increasingly contradicted by the evidence we are unearthing." [In Photos: New Human Relative Shakes Up Our Family Tree]

Modern humans first appeared in Africa about 150,000 to 200,000 years ago, and recent archaeological and genetic findings suggest that modern humans first migrated out of Africa starting at least 100,000 years ago. However, a number of earlier groups of so-called archaic humans left Africa beforehand; for instance, Neanderthals lived in Europe and Asia between about 200,000 and 40,000 years ago.

The fragmentary nature of the human fossil record has made it tricky to determine the biology of the immediate predecessors of modern humans in eastern Eurasia, Trinkaus said. Unearthing details from this region could shed light on an otherwise poorly understood aspect of human evolution, yielding insights into how modern and archaic humans interacted, he added.

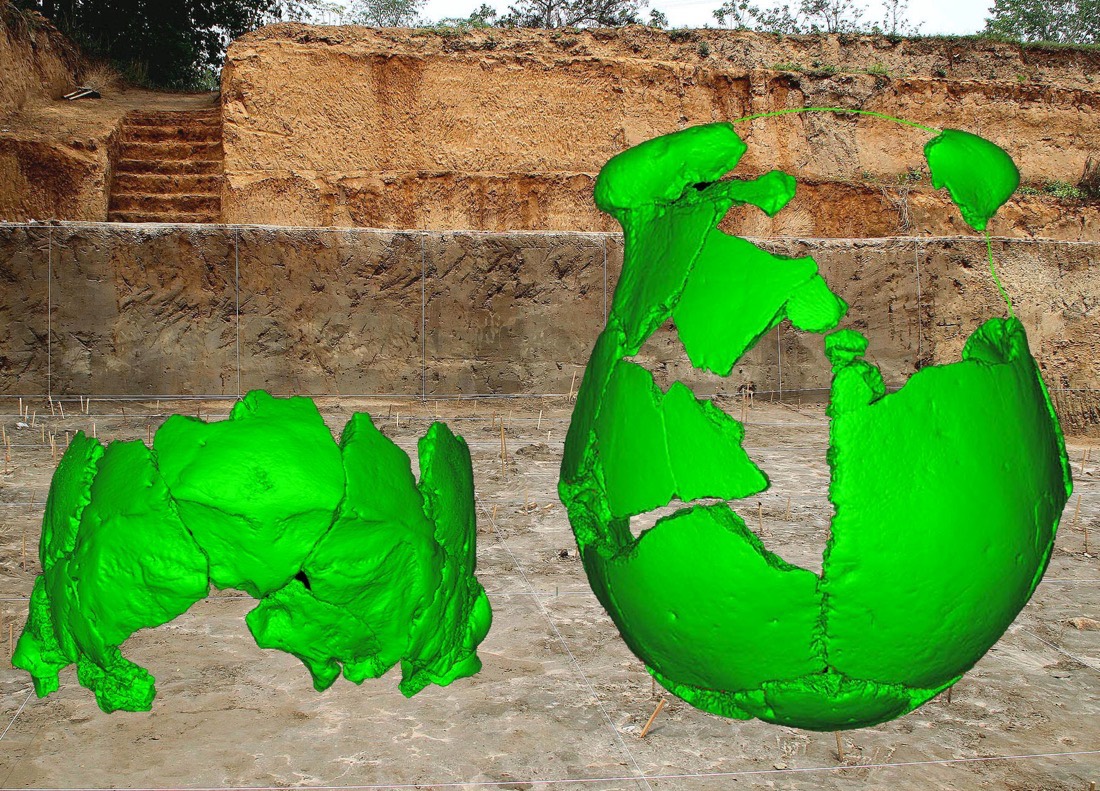

In the new study, scientists analyzed fragments of two human skulls that lead study author Zhan-Yang Li, an archaeologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, unearthed during fieldwork in the city of Xuchang in central China between 2007 and 2014. The fossils are about 105,000 to 125,000 years old, the researchers said.

Back when these ancient humans lived, the site where they were found was a spring-fed lake amid a mosaic of open grasslands and some forests, said study co-author Xiu-Jie Wu, a paleoanthropologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Researchers found fossils of more than 20 other mammal species there, including those of rhinos, deer, horses, gazelles and rodents, and about one-sixth of these bones had cut marks, suggesting that humans preyed on them, Wu told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The partial human skulls combined the features seen in different groups of humans across Eurasia. Like early modern humans, these skulls had large brains and modest brow ridges, the researchers said. However, like earlier humans from eastern Eurasia, the skulls had low, broad braincases. In addition, the semicircular canals in the skulls' inner ears and the arrangement of the rear portion of the skulls more closely resembled the features of Neanderthals from western Eurasia, the scientists said.

This collection of features in central China suggests that populations of humans across Eurasia were more connected with each other more than previously thought, Trinkaus said.

"We're seeing a general interconnectedness of all these populations across the Old World," Trinkaus told Live Science. "Features that we might normally think of [as] belonging to one region or another do appear across the whole range of populations, although the frequency at which those features appear may differ across regions."

Fieldwork in this region will hopefully unearth the complete skull (showing the face) and teeth of these ancient humans, "so we can tell what they looked like," Wu told Live Science.

The scientists detailed their findings in the March 3 issue of the journal Science.

Original article on Live Science.