Seafloor Robot Breaks World Record While Collecting Climate Data

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

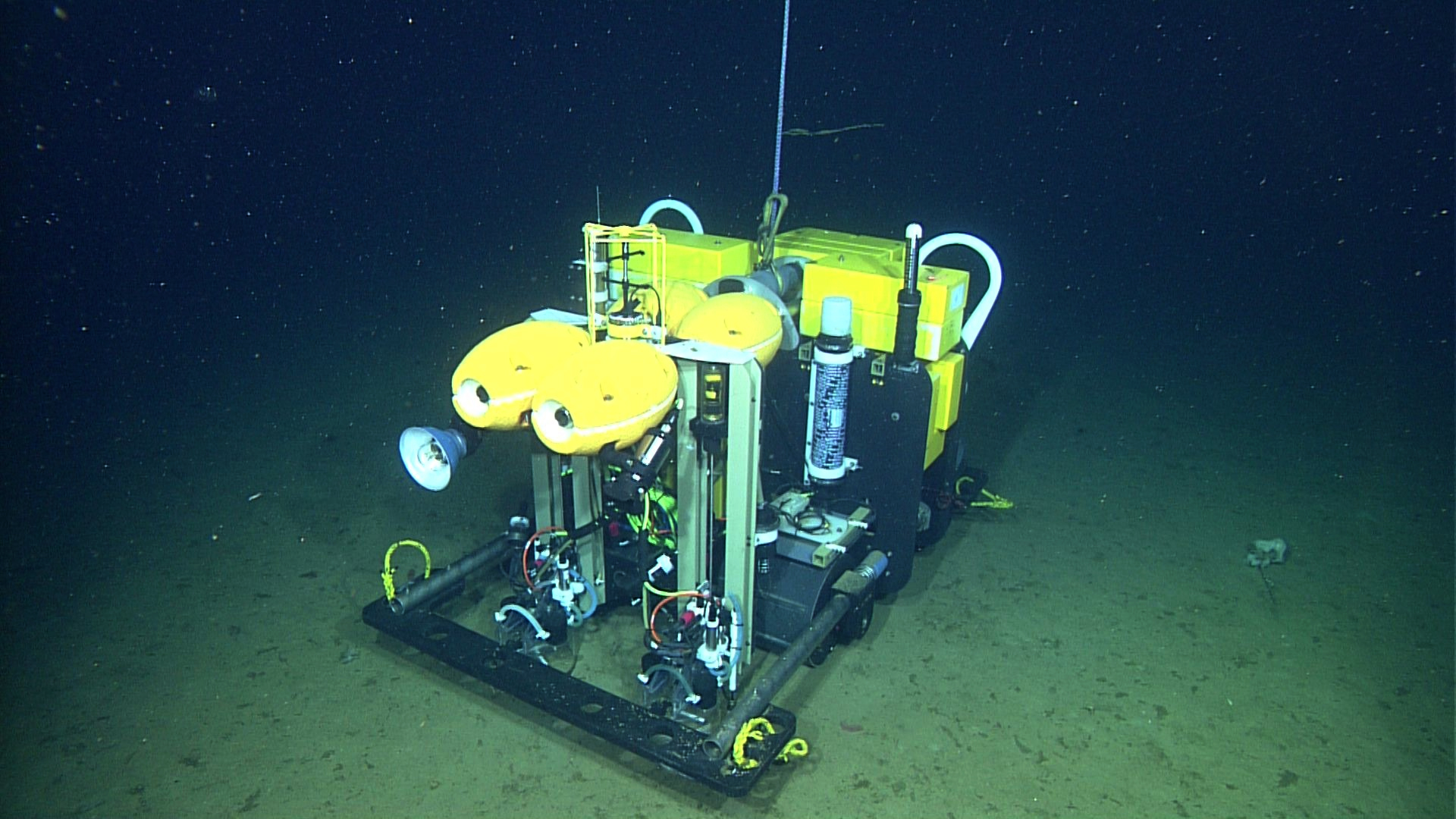

A robot that crawls over the abyssal seafloor collecting data on fecal matter and other bits of "marine snow" just broke the world record for longest seafloor stay at 367 days, and longest distance traveled (about 1 mile, or 1.6 kilometers) by any of its kind.

To be fair, the robot is the only of its kind, and the record it broke was its own.

The Benthic Rover, a project of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), is an untethered, autonomous seafloor crawler. It is deployed in an area known as Station M, 136 miles (220 kilometers) from the California coastline, and 2.5 miles (4,000 meters ― the abyssal zone) below the surface. The bot is tasked with measuring the seafloor community's consumption of marine snow — organic material from animal poop, zooplankton (tiny marine animals) and phytoplankton that falls from the upper layers of water and into the deep ocean. [Images: Strange Life Along Antarctic Seafloor]

A team of MBARI researchers have been studying Station M since 1989, and the Benthic Rover has helped them see more clearly how the seafloor ecosystem is affecting and being affected by climate change.

"A major unknown component of the global carbon cycle is the amount of organic carbon that reaches the deep ocean and its ultimate utilization or long-term sequestration in the sediments," MBARI's senior scientist on the project, Ken Smith, wrote in a 2013 paper on the subject.

When marine snow falls to the seafloor, some is eaten by deep-dwelling organisms that respire it as carbon dioxide, and some is buried in seafloor sediment. Data on how much carbon is respired and sequestered is important for climate science, because the gas is a greenhouse gas that intensifies warming in the atmosphere when released.

When deployed along the seafloor, the autonomous rover takes overlapping images every meter with a high-resolution camera. It also has a fluorescence-imaging system that detects the pigment called chlorophyll from phytoplankton in the marine snow that sank from the surface waters. Each day, the Benthic Rover lowers two chambers into the seafloor to measure how much oxygen is being consumed by organisms in the mud, something that reveals how organic carbon is being used.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One significant finding from the rover's deployments over the past few years was the detection of several large pulses of marine snow that rapidly sank to the seafloor. Several of these brief pulses, which lasted two to four weeks, would dump nearly an entire year’s worth of nutrient-rich debris on the seafloor. The pulses could be related to stronger winds along the shore, which drive the upwelling of nutrients in coastal waters.

According to MBARI, the pulse events would have gone undetected without the Benthic Rover's long-term presence in Station M.

"In documenting such events, the Rover helped solve an important piece of Earth's carbon-cycle puzzle — showing that a much larger percentage of carbon than previously expected can sink rapidly from the surface into deeper water," according to an MBARI statement. "These periodic events can now be factored into global climate change models."

After recovering the rover for maintenance in November 2016, MBARI deployed the Benthic Rover back to the seafloor at Station M. The research institute expects the rover to operate for roughly another year before another maintenance recovery.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus