Russian River Runs Red

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

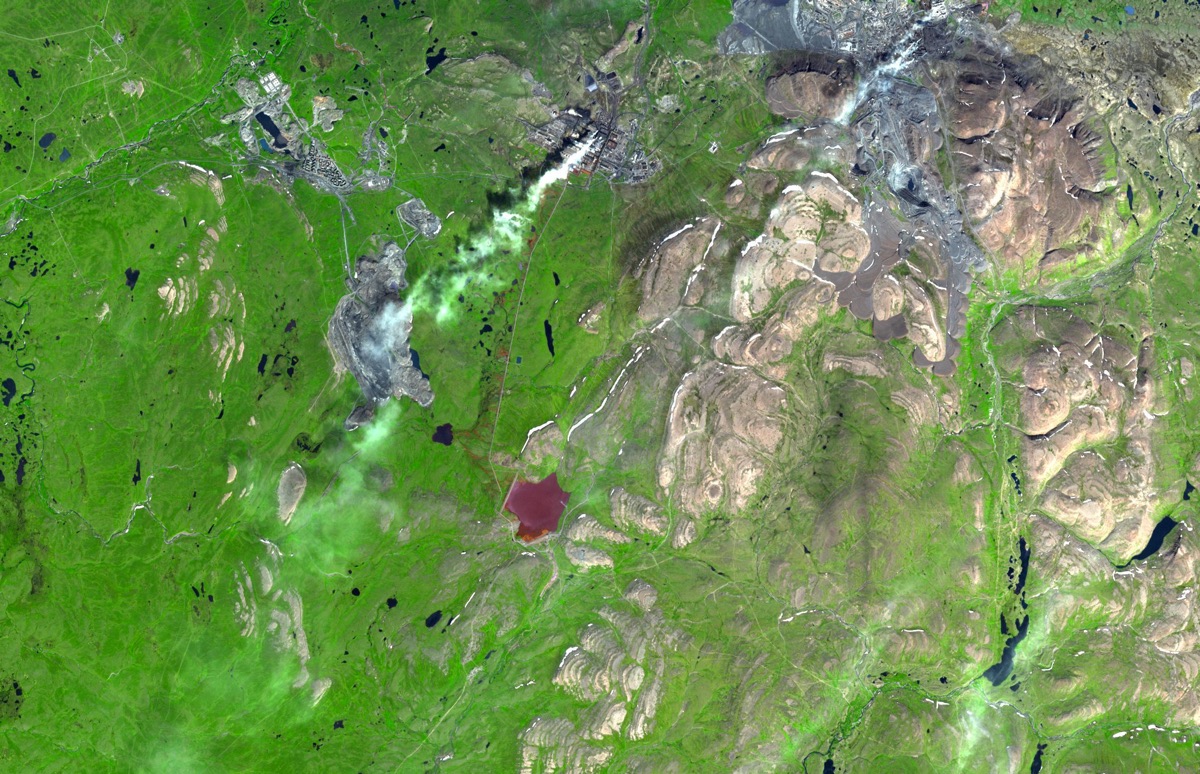

A river in Russia has turned bright red, and pictures of the spectacle are circulating on social media.

The Siberian Times reported on Sept. 7 that the Daldykan River near the city of Norilsk had turned the color of blood, with locals pointing fingers at the nearby Nadezhda Metallurgical Plant, owned by the company Norilsk Nickel. In fact, a broken pipeline at the plant may be the culprit, according to a statement from the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources. The company, however, has denied any accidental discharge of pollutants. The company did not respond to Live Science's request for comment.

Norilsk Nickel does have a history of environmental problems, however. In 2014, a company plant in Harjavalta, Finland, released 66 metric tons (72.7 U.S. tons) of nickel into the Kokemäenjoki River, sending nickel levels soaring far above safe limits. Finland Times reported at the time that levels in the river in the city of Pori reached 530 micrograms per liter. Safe drinking levels are below 20 micrograms per liter. The water in the Kokemäenjoki did not turn red, however. [Photos: The Strangest Places on Earth]

Norilsk is no stranger to struggles with pollution. In 2007, the city appeared on the top 10 list of worst-polluted places on Earth, in a report released by the environmental group the Blacksmith Institute. The city also consistently ranks as the most-polluted city in Russia, according to government statistics.

According to the Blacksmith Institute, Norilsk is home to the world's largest heavy metals smelting complex, and is the source of all this pollution. The soil around Norilsk has been so polluted that, according to NASA, it can actually be mined: It contains economically useful levels of palladium and platinum. Each year, the smelters release nearly 2 tons of sulfur dioxide into the air above Norilsk — emissions that cause acid rain and have reached as far as 124 miles (200 kilometers) away, according to a 2003 study in the Russian Journal of Ecology.

A 1995 review of research on public health in Norilsk, published in the journal Science of the Total Environment, found higher-than-average rates of cancer and cancer deaths, higher-than-average rates of premature births and high rates of respiratory disease in children. A 1985 dissertation study found that children living closest to the nickel plant were 1.5 times more likely to have respiratory, ear, nose or throat diseases than those living farther away.

While it remains unclear what caused the Daldykan River to flow crimson, mining and industrial processes have caused similar problems in other places. In 2015, wastewater from a long-abandoned mine in Colorado flowed into the Animas River, turning the water a striking orange color.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Red waters aren't always a sign of doom and gloom. This summer, Iran's Lake Urmia turned from green to blood red as a result of microorganisms that thrive on salt and light. The Blood Falls of Antarctica get their scarlet hue from bacteria hiding out in the briny water beneath the glacier there. Salt-loving archaea microbes turn Utah's Great Salt Lake a rosy pink.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus